At the end of the 18th century, a movement in music, art, and literature began to sweep across the Western World. Later named “Romanticism”—from the French word roman, meaning “story” or “tale”—it was a radical departure from the so-called “Age of Reason” that preceded it, an era that emphasized social issues; journalism, literature, and the other arts as tools for teaching ethics, morality, science, and logic over organized religion; and—most especially—the use of reason rather than emotion.

Enter Beethoven and Berlioz in music, Goethe and Wordsworth in literature, and Goya and Gros in art—to name just a few towering figures—and everything became upended. Empirical philosophy was replaced with a focus on individuality, democracy, and personal freedom. Interest in Greek and Roman philosophy was enhanced by the study of those cultures’ mythologies. Suddenly there was a fascination with the supernatural world, with the celebration of the simple life (especially the rural versus the urban), with women’s rights (side by side with the idealization of the Eternal Feminine), and with the importance of everyday language and common subject matter. Yet undeniably, the two greatest focal points of Romanticism were Nature and the Hero.

Nature was the great Teacher; it was the supreme Religion. It was the place you went to regain your true self, and elements of Nature were frequently personified and anthropomorphized so that clouds wept, brooks babbled, and winds roared. As for the Hero, he (and a few women, like Queen Boudica of the Celts) was often misunderstood or an outcast. He was a wanderer through life spiritually and often geographically. Indeed, suffering and starving artists as well as their feelings formed an important part of the core of the Romantic Arts.

So, walking through—and contemplating—the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s 2025 retrospective of the 19th century painter Caspar David Friedrich affirmed my belief that his work remains a brilliant embodiment of the key elements of Romanticism. Living from 1774 to 1840, Friedrich was born in the town of Greifswald on the Baltic Sea, studied art in Copenhagen from 1794-1798, settled in Dresden, and married quite happily at the age of 44, eventually becoming a father of three. He was primarily a landscape painter with his work conveying a subjective, emotional response to the natural world. As William Vaughan says in his 2004 biography of the artist, “[Friedrich] sought to present nature as a divine creation to be set against the artifice of human civilization.”

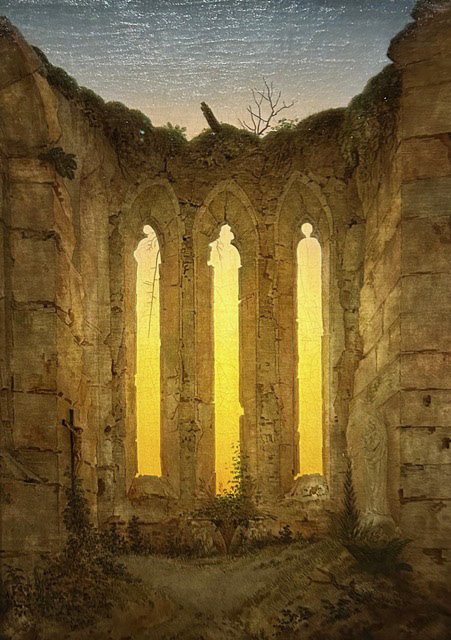

This juxtaposition of imagery reflects both his Lutheran upbringing and the Romantic search for spirituality in Nature. So, for example, his 1812 painting Cross in the Forest uses a traditional religious symbol that becomes part of a wooded landscape, suggesting that the Cross and the forest are both divine elements. Building on that theme, Ruins at Oybin (also from around 1812) presents us with an abandoned chapel, which becomes an emblem both of the fragility and the continuity of faith. The monastery is empty, but it holds on, slowly being subsumed by the Nature around it.

Meanwhile, one of Friedrich’s prominent devices is his use of Rückenfigur, which means “back figure.” In numerous paintings—including his 1817 masterpiece Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog—he portrays his subject from behind, inviting the viewer to dialogue with the landscape beyond the mysterious principal character. In Romantic works of art, music, and literature, you frequently find such solitary beings who are quite often misunderstood outcasts seeking solace in the natural world. In addition, we see the solid mass of a mountain’s stones and boulders contrasted with the illusive clouds and mist, symbolically juxtaposing permanence with fluidity and transience. For the Romantics, majestic mountains presented an encounter with the Sublime—an otherworldly confrontation with raw beauty, danger, and awe. Thus, in many ways, the figure of the metaphorically named “Wanderer” becomes the quintessential Romantic.

Finally, looking at Wanderer, we see yet another characteristic Romantic theme: the immensity of Nature as compared to the literal smallness of humans. One of the hallmarks of many Romantic paintings is the presentation of vast skyscapes (although we can see this trend going back to Renaissance landscapes, especially those of the Dutch masters). In Monk by the Sea (circa 1808-1810), for example, most of the painting is dominated by the sky. The monk (is he praying or meditating?) is alone and nearly insignificant; he is seen as a small part of a much grander scheme, an ant surveying the Cosmos.

We see an impressive variety of “big skies” in Friedrich’s work, including the prismatic sunset in The Stages of Life from 1834, the mystical nightscape in The North Sea in Moonlight painted circa 1824, and the vast expanses on display in Rocky Reef off the Seacoast (c. 1824), a work that also illustrates Friedrich’s recurrent and symbolic use darkness and light.

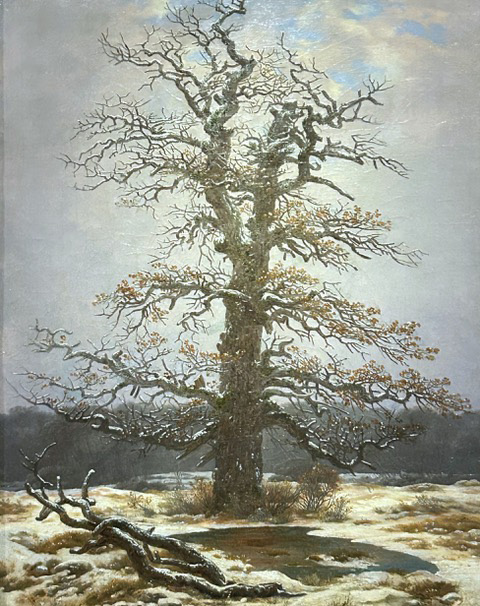

The majestic oak that fills the canvas in Oak Tree in the Snow (circa 1828) is not only a potent symbol of Nature, but also representative of das Volk (“the people”) and their rootedness in the land—a people with a shared culture, history, and hope, which we see portrayed in the small patch of blue above the crown of the tree. And finally, there’s Two Men Contemplating the Moon (circa 1825-1830), a veritable compendium of Romantic themes and images: moonlight, a forest, camaraderie, “the great outdoors,” mindful meditation. We are no longer looking at an 18th century historical or “moral” painting. No, here we are witnessing a private moment shared by two men beholding the night and its preternatural lunar mysteries.

Simply put, just as when you read Goethe’s Sorrows of Young Werther or listen to Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique, when you truly look at (and into) a painting by Caspar David Friedrich, you are looking into the very soul of Romanticism. G&S

Leave a Comment