As the Portland Art Museum begins to re-open several of its galleries during the construction of an additional 95,000 square feet of exhibition space, including its Mark Rothko Pavilion, visitors can now explore a remarkable collection of sacred art rarely seen outside Central and South America. These stunning works in the American wing are the bequest of Elvin Duerst (1915-2006) who was an Oregon-born foreign aid worker for the United Nations, The Institute of Inter-American Affairs, and Stanford University. What enthralled Duerst was the rich heritage of colonial art south of the border.

And much of that art—especially from the 16th through 18th centuries—was evangelical in nature. Though the often-brutal Spanish conquest of the region (which began in 1532) was rooted in greed for mineral deposits and other natural resources, the principal justification for the colonization of the Americas was—quite ironically—a spiritual one. Roman Catholic missionaries flooded the region over the years, and rather than rejecting their message, indigenous peoples responded strongly and positively to the new “European gods.” Artists from Italy, France, and Spain were brought over to train native talent, and distinguished art schools arose—especially in the former Incan regions of western South America—that filled the demand for cathedral art and personal devotion.

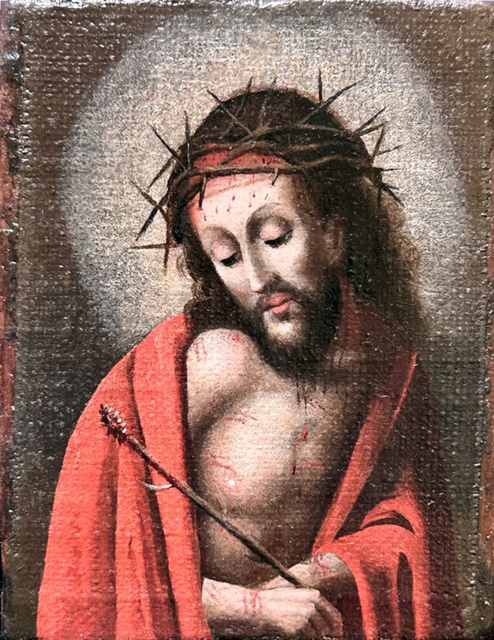

The Duerst Bequest focuses on icons, archangels, saints, and “statue art,” each with aspects found nowhere else in Renaissance or early Modern art. Take, for example, the miniature icon called Ecce Homo, an oil created on canvas and mounted on panel dating from around 1600. This 3-by-4 inch rectangle depicts a moment from the New Testament in which Pontius Pilate utters the words “Behold the Man” (Ecce Homo). But unlike its more austere European equivalents, this devotional piece by an anonymous artist is filled—like other similar small icons from the Andean region—with drama. It takes several different moments from the Passion story, conflating them into one momentous scene in which Jesus not only is wearing a crown of thorns and holding an instrument of torture, but is also vividly sprinkled with blood.

There’s also much drama in the bold depictions of archangels. One portrayal that dates from the 1670s—possibly by the important Bolivian artist Leonardo Flores (1650-1710?)—shows Rafael, an archangel found in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. As the protector of travelers and pilgrims, here he is depicted in mid-stride, carrying a walking staff, his path lit by golden rays from heaven. He also holds a fish, a reference to a story found in the apocryphal Book of Tobit in which Rafael cures a blind person using fish gall. What stands out most, however, is the costume. In much colonial South American art, archangels are depicted in distinctively flamboyant finery, usually with billowing capes. In this work—created for exhibition in a cathedral—the fantastic regalia combines a woman’s dress with a man’s Roman military boots to show that archangels are sexless and other-worldly soldiers—perhaps making the pronoun “he” problematic.

Another archangel in the collection—by an unknown artist that dates from around 1730—portrays Gabriel. Here the androgynous heavenly being is dressed in a costume that includes a feathered hat and be-ribboned high heel pumps. What identifies the being as God’s principal messenger is the multicolored signal banner, a variant of one that the artist might have seen in a Dutch military handbook.

Ultimately, these archangel portraits and other works by Bolivian and Andean artists are examples of the Mestizo Baroque, a unique style of art (and architecture) that blends elements of traditional Spanish and European Baroque with indigenous New World colors and symbols; the result is a distinctive fusion of both European and vibrant native motifs.

Of the saint portraits seen in the gallery, the depiction of Saint Agnes by the so-called Master of Calamarca is one of the most engaging. The Master—a Bolivian artist whose real name was José López de los Ríos—flourished during the first half of the 18th century. Though most well-known for creating two series of extraordinary angels and archangels that adorn the walls of a Catholic church in Calamarca, Bolivia (hence the artist’s moniker), de los Ríos also painted portraits of saints for family chapels and personal contemplation. In this piece, Agnes is wearing a highly ornate European dress with a flowing red cape and is being crowned with roses by a childlike angel, indicating that she will die violently because of her strong belief in Jesus—who is represented by the Lamb she cradles close to her bosom. These kinds of portraits became extremely popular throughout Colonial Central and South America and remain examples of the amalgamation of European and indigenous traditions.

Similarly, statues—especially of the Madonna and Child—rapidly became objects of veneration throughout the Andean region, which led to the development of pilgrimage sites. The Incan culture had a long tradition of dressing their ritual objects in lavish fabrics and jewels, so when Catholicism was introduced, Native artists began to adorn their Christian statues in equally fabulous and sumptuous finery. Throughout the New World, paintings of these statues became important souvenirs of a pilgrimage as well as objects of devotion in their own right.

One of the most detailed of these so-called statue paintings is The Virgin of Pomata, attributed to the early 18th century Bolivian artist Juan Tupu Chili. Rhea feathers (a flightless bird native to the Andes), rose garlands, and elaborate crowns fill the canvas in an explosion of warm colors. Although the portrait is an artistic interpretation of the original miracle-working statue (located in a shrine on the Peruvian side of Lake Titicaca), both that original statue and the painting itself were seen as possessing intercessory power for the believer.

To round out the gallery, the curators add a brilliant twist: They have included two Nayarit ceramic figures from Western Mexico, one created as far back as 200 BCE and the other in 300 CE. These doll-sized Pre-Columbian statues stand watch over the paintings of the Duerst Bequest, as if communicating with those vivid images from a millennium and a half later.

What we see in these Pre-Columbian statues and in the exuberant Colonial period art that surrounds them is a reflection of the rich history of the indigenous people of the Americas. This gallery shows that despite the Spanish conquest of their lands, native artists remained true to their heritage, that the subject matter of the art may have changed, but the traditions and spirit intrinsic to that art never did. G&S

Leave a Comment