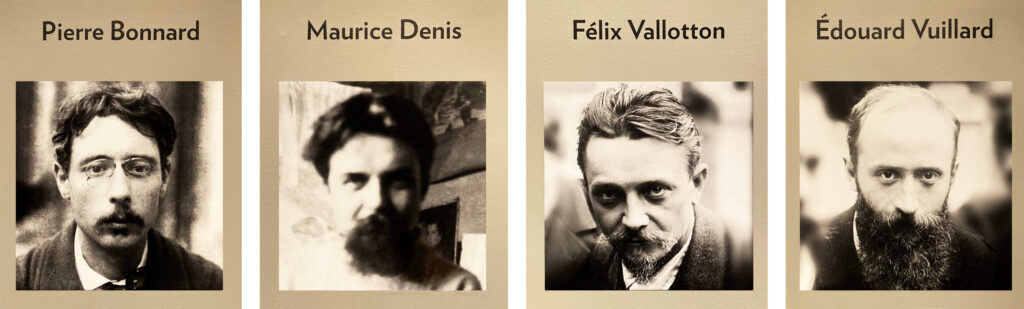

Grandparents, mothers, fathers, sisters, brothers-in-law, cousins, wives, children, patrons, friends, and pets: these are the constant cast of characters that inhabit the canvases and prints of a group of four artists who called themselves the Nabi Circle. Pierre Bonnard —arguably the most well-known of the four today— and his friends Maurice Denis, Félix Vallotton, and Édouard Vuillard adopted their name Nabi from the Hebrew word for “prophet” —Nebiim— to reflect their intent to create a new school of art that made suggestion and sensation more important than the literal depiction of people, places, and things. They were ultimately part of the Symbolist Movement of the 1880s and 90s that also occurred in literature, music, and theater, a movement that sought to express a mystical and emotive understanding of the world around us.

Gift of David Allen Devrishian 1999.180.1

Thanks to the Cleveland Museum of Art in conjunction with the Portland Art Museum, a current major retrospective —called Private Lives— reveals the complex nature of the Nabis’ work. (Several superb essays in the sumptuously illustrated exhibition catalogue focus on that complexity.) These four men used their own lives and family members as well as their homes and immediate surroundings as their subject matter; we get an autobiographical world that expresses universal depths of feeling, memory, nostalgia, joy, and melancholy.

The show is presented thematically, with separate sections devoted to The Intimate Interior, The Troubled Interior, Family Dining, Domestic Work, Landscapes, and Intimacies, among others. As one moves through the nearly 190 prints, paintings, posters, and watercolors there is always a sense of closed-in spaces, but often to the point of suggesting claustrophobic confinement and rumbling tensions. We enter quiet interiors, watch families gathered around a dining room table, and smile at scenes of children with household pets in living rooms, gardens, and parks. What emerges as we promenade through the various exhibit rooms are works that evoke both joy and real-life strains, both the home-spun tragedies and the mysteries of day-to-day life.

Pierre Bonnard’s The Children’s Meal from 1895 —painted on cardboard and mounted on wood— is one of the iconic pictures of the show. Measuring approximately 24 × 30 inches (59 × 74 cm), this work is similar in size to many other pieces—indeed, the intimacy of the Nabis’ world is reflected in the dimensions of their art. We are not given vast canvases or large posters; we are invited to enter confidential, personal spaces. This particular work shows Bonnard’s mother, daughter, and two grandsons all crowded around the dining room table, but it is the two children who dominate—one attempting to feed himself, the other regarding the viewer with a calm expression. The women’s faces are misty suggestions.

In The Lamp, Bonnard once again puts us around the family table, but this time with an ornate, suspended lamp dominating the picture. Bonnard adored animals, and cats were always welcome companions at —and on— his family table. In this 20 x 24 inch (54 x 61 cm) oil on board, a small tabby joins the artist’s mother, sister, and nephew under the golden light of the enormous brass chandelier, with the glass fuel reservoir reflecting the scene back to the viewer. The psychological familiarity of the scene is heightened by the dim lighting, with the food, the cat, the people, and the ornate lamp all crammed into a very small space.

One of the other things that the curators of the show —Heather Brown (Cleveland Museum of Art) and Mary Chapin (Portland Art Museum)— also emphasize is the Nabi fascination with —obsession with?— the wallpaper designs of William Morris and others. To underscore that, many of the walls in the exhibit are covered with duplicates of the intricately patterned papers of the period that are also found in Nabis’ paintings and prints.

One of the more unsettling uses of that wallpaper motif is found in Édouard Vuillard’s 1893 oil painting Interior, Mother and Sister of the Artist. This emotionally complex painting depicts the two women with whom he shared his home. Unlike the comfortable familiarity of Bonnard’s family groupings, this one suggests dis-ease and discord. Madame Vuillard dominates the scene, sitting imperiously, like a queen on a throne. His sister, Marie, barely fits in the canvas; she’s hunched and cowering against the wall, and the print of her dress and the pattern of the wallpaper seem to meld, giving the disquieting illusion that she’s melting into the wall itself, a victim of her mother’s dominance.

New York Gift of Saidie A. May 141.1934

Not unlike Vuillard, Félix Vallotton also explored psychology and ambiguity within a close setting. In 1897, he produced a series of black and white woodcuts called Intimacies that presented extremely personal moments, usually between two people. One of those pieces is called The Lie; it’s only 7 x 9 inches (17 x 22 cm). The following year he created a similarly-sized oil version. Both depictions show a man and a woman sitting in an embrace on a couch. It appears that the woman —who wears a startling red dress in the painted rendering— is whispering something into the man’s ear. What’s “the lie” that she’s telling him? I’ll always love you… The child is yours… I promise to tell my husband… Like so many other Vallotton interiors, the nearly miniature woodcut and painting are awash in ambiguity and beg for the viewer’s interpretation.

The Baltimore Museum of Art, The Cone Collection,

formed by Dr. Claribel Cone and Miss Etta Cone of Baltimore, Maryland. BMA 1950.298

There’s no ambiguity of mood in Maurice Denis’s Little Girl in a Red Dress (also known as Child with Apron). Here, Denis uses repetitive dashes of pink and red to describe both the flowers in the garden and the girl’s checkered dress. When the sister disappears into the wall in Vuillard’s Interior, it’s terrifying; in Denis’s portrait, when the little girl and her colorful dress seem to meld into the garden, it suggests a joyous, playful kinship between the child and Nature itself.

The four artists of the Nabi Circle created focused, personal images that weren’t intended to be realistic, recognizable portraits. Rather, the Nabis strove to capture feelings, including devotion, familial tension, and the transience of happiness and life itself. This exhibition allowed four talented friends to be in dialogue with one another. It was the great achievement of the curators who made it possible for us to be part of this deeply satisfying conversation.

very enjoyable

enjoyable