In the 1920s, World War I and the 1918 influenza pandemic were over. Women could finally vote. The stock market was rocketing skyward. Remnants of Victorian prudery were fading fast. The young generation was ready to party.

Despite Prohibition, city speakeasies and rural roadhouses offered long menus of cocktails. Movie posters featured the smoldering eyes of Rudolph Valentino and the seductive poses of Mae Murray (“the girl with the bee-stung lips”). Prominent socialites outdid one another at the annual Beaux-Arts costume ball at New York’s Hotel Astor, and Butterick sold inexpensive dress-making patterns for do-it-yourself masquerade partyers. Jazz, blues, swing, and ragtime played on gramophones and radios throughout the country. Broadway musicals and revues made George Gershwin and Irving Berlin household names. Although segregation persisted, barriers among genders and races increasingly dissolved in nightspots.

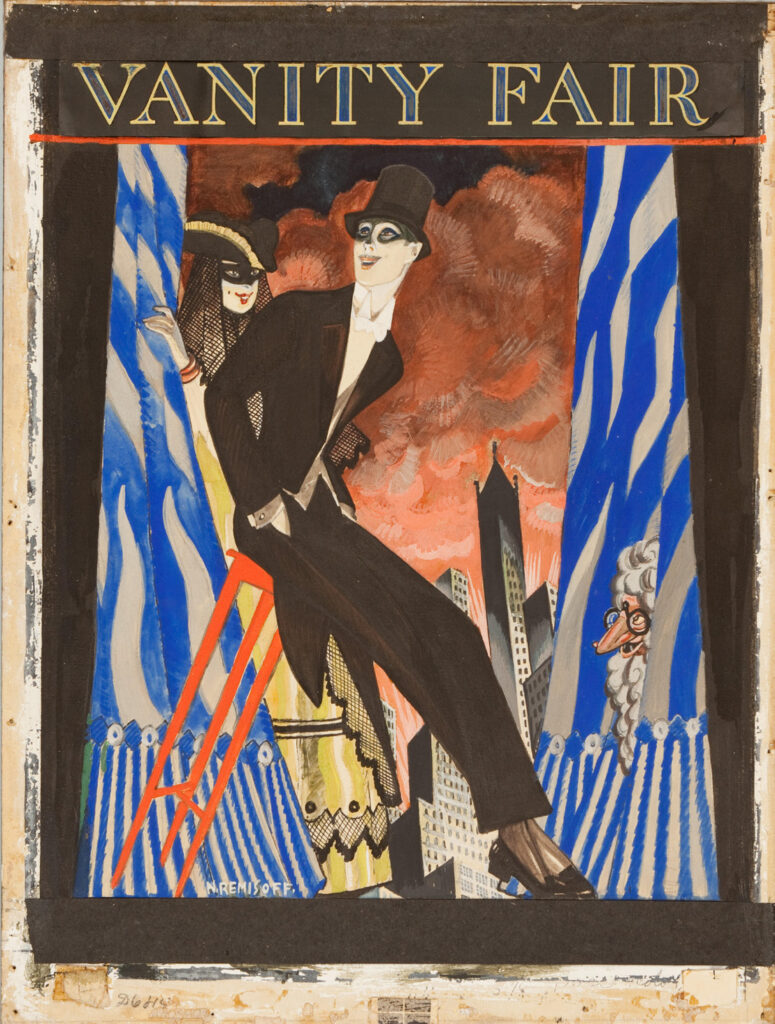

Between them, Vogue and Vanity Fair covered it all—chic fashion and luxury goods, music and theater, modern art and literature, satire, politics, society, and glamorous celebrities. Vogue attracted a middle class, aspirational audience, while Vanity Fair cultivated a more affluent, urban one. By 1920, publishing magnate Condé Nast owned both, and he hired top-tier illustrators. Helen Dryden and Nicolai Remisoff were among them.

Dryden arrived in New York after studying art in her native Baltimore and Philadelphia. In 1910, she won a contract with Vogue. For the next 13 years, she created scores of covers in a distinctive linear and colorful style. She expressed her love of 18th- and 19th-century French art, and the innovative, fanciful colors of Léon Bakst’s costume designs for the Ballets Russes.

Her December, 1922, cover brings together such historical and modern tastes and captures a momentary romantic encounter. Dryden’s coy young woman looks at a masked man with copper-colored hair and lavender trousers, who offers her—with studied nonchalance—a rose. His two-tone cape, cinched frockcoat, extravagant polka-dot necktie, and opera pumps evoke the “dandy” poseur of post-Revolutionary France and Regency-era Britain, epitomized a century later by Oscar Wilde. Her strapless gown, which would have been daring even for the free-wheeling 1920s outside the Ziegfeld Follies or movie ads promoting Theda-Bara-as-Cleopatra, reflects the masquerade’s traditional license for risqué behavior.

Although segregation persisted, barriers among genders and races increasingly dissolved in nightspots.

Her lowered veil is an airy confection similar to Dryden’s eight precisely-detailed illustrations for the article “The Historic Seven Veils Are Rivalled by Eight Modern Ones” a month earlier in Vogue’s November 15, 1922 issue. The flowered bell-skirt conjures up 18th century French paintings of aristocratic women, Victorian ball gowns, and Lanvin’s contemporary robe-de-style. Although Dryden’s graceful lines recall Art Nouveau, bright red lipstick and long arched eyebrows required up-to-the-minute make-up. The curtain and floral swags could be a stage setting similar to the tableaux in productions such as Irving Berlin’s 1921 Music Box Revue, which featured actresses in comparable dresses.

Later in Dryden’s career in illustration and theatrical design, when she was reported to be the nation’s highest paid woman artist, she brought her talents to industry. Studebaker’s 1936 tagline announced “It’s styled by Helen Dryden.” As Sarah Marie Horne notes in her study of the artist, “If Dryden were still around today, in the age of YouTube and Instagram, there is no doubt we would all be calling her an influencer.”

The same might be said of Nicolai Remisoff. Born Nikolai Remizov in St. Petersburg, Russia, and a 1918 graduate of the Imperial Academy of Arts, he fled to Paris when the Bolshevik regime attempted to prosecute him for his political cartoons. His role as the scenic designer for La Chauve-Souris (the bat), an international revue company, brought him to New York in 1921. Remisoff ‘s next three years in the city also encompassed illustrations for Vogue and Vanity Fair. In 1925, he continued his career in Chicago and, in the late 1930s, began 31 years as a Hollywood movie and television set designer.

Remisoff’s March, 1923, Vanity Fair cover is an interplay of patterns, angles, curves, ambiguous time and space, and witty interactions in primary colors, rather than a straightforward narrative. A figure in white-tie-and-tails—more formal evening-dress than a tuxedo—balances daringly in front of stage curtains and smiles upward as if at the balcony. His shadowed eyes suggest a mask or stage make-up; his attire and slim build conjure up Broadway-star dancers Vernon Castle and Fred Astaire. As a masked woman in a gown and veil pulls the curtain back and smiles appreciatively at him, he becomes both a performer and a theatergoer. Beyond her, a set decoration of tilted, Art-Deco-style skyscrapers embodies the city’s dynamism. Peering from the folds of the right curtain is a caricature of William Makepeace Thackeray (with his curly white hair and round glasses), author of the moralizing novel Vanity Fair (1847-48). Wide-eyed, he grins salaciously as if he can’t believe his good fortune in observing such libertine amusements. Actors and audience, theater space and cityscape, novel and magazine shift wondrously throughout the scene.

One commentator noted the “disarming humor and vivid palette” of Remisoff’s work, qualities that also enliven Dryden’s art. Both artists distilled the sensuality and optimistic spirit of the early 1920s as well as a national sensibility that—in the best interpretation of the phrase— “all the world’s a stage.” G&S

Delart.org

Coming in the fall: Jazz Age Illustration. Delaware Art Museum, Oct 5, 2024-Jan 26, 2025

Leave a Comment