In DRIFT filmmaker, Elizabeth Lowe, manages to envision a religion, people it with saints, perform its most primal ritual and lay at its altar visual offerings of her art. There is an irony here that may not be all that uncommon: the tribute she lays at the feet of her heroes, at least in the context of this film, outshines them. She is the blesséd supplicant who, through worship, is beatified.

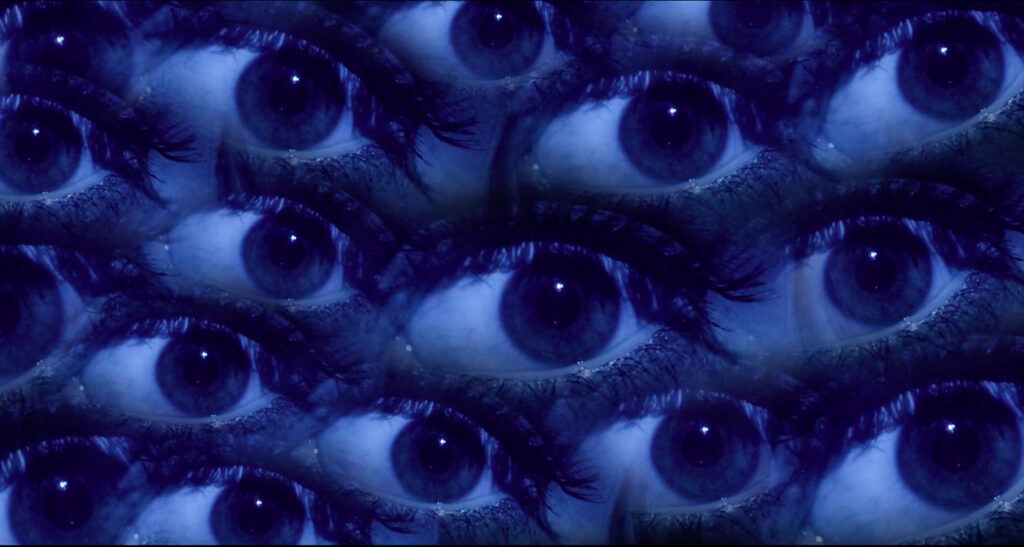

To watch DRIFT is to know that Lowe is an image maker. Her powerful electronic assemblages seduce the viewer, who is then drawn down an illuminative path of textual and visual commentary in homage to the art of,” “and belief in, Cinema. Like the great painters of the early Renaissance whose art had to serve a religious purpose, Lowe’s work in DRIFT must serve an ulterior academic one: earning an MFA without compromising the film’s value as art, at once viewable and informational. She succeeds by inventing a mode of devotional exposition that borrows from religious practice. While Fra. Angelico’s masters were a god in a heaven and that god’s earthly interlocutors, Lowe’s, in DRIFT, are the cinema in its nascent, silent, intensely visual form and its earliest innovators, especially but not exclusively its women.

DRIFT is basically a silent film that has been technologically liberated. It is lushly soundtracked by Sound Designer, Calvert Cruz. Cruz’s range of musical and practical sound supports with a graceful reserve the flow of Lowe’s imagistic river. Into that river Lowe feeds a mélange of old and new media. She makes images with an assortment of film cameras, the kind that make pictures on the noble and fading medium of celluloid and processes these images with layerings of color and montage. The result is a form of technological homage to Lowe’s pantheon of women who directed silent films in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. For them, we may guess, the shapeshifting power in this 21st century woman’s electronic toolbox would have been the stuff of dreams. Meanwhile, Lowe seems to be reaching back in time in search of communion with her heroes from the primordial beginnings of cinema. And here, perhaps, in that tension between past and present, new and old lies the charm of this film: it is filmmaking’s past, seen through, adorned and revered by youthful eyes.

LET MY SOUL DRIFT

THROUGH PATTERNS AND

PECULIARITIES.

To Antelope Island, that gem of Utah’s off world beauty surrounded as it is by the mercury-like stillness of The Great Salt Lake, she brings a Bolex. This is the do-it- all camera through which passed much of the 16mm film that gave rise to the now ubiquitous term, “experimental.” An art student with an idea for a film in 1961 was lucky to find the versatile Bolex and not an old WWII newsreel camera in the equipment closet next to the art department’s dark room. Lowe uses it to make, in effect or in fact, a double exposure in which she chases down and beats herself to death with a baseball bat.

AS I ENTER THE HOLIEST OF HOUSES,

I SURRENDER ALL

PRE-CONCEIVED NOTIONS OF CINEMA.

It is arguable that the filmmaker performs this ritual act to illustrate her concept of death and resurrection through art or Cinema, the religion. By choosing to shoot it on film, with so many more modern tools available to her, Lowe extends the resurrective symbolism of her performance to the medium on which it is recorded. An ornately framed, silent movie-style title card that reads, “DEATH ON CELLULOID,” precedes the murder by self-cited above. Another furthers the life, death, resurrection analogy quoting film director, Robert Bresson, from his book, Notes on the Cinematograph, “My movie is first born in my head, dies on paper; is

resuscitated by the living persons and real objects I use, which are killed on film but, placed in a certain order and projected onto a screen, come to life again like flowers in water.”

This textual thread — proclaiming, supplicating, provoking — weaves through the fabric of Lowe’s visual tapestry in much the same way that title cards gave “voice” to actors and furthered story lines in the great silent movies, the great picture stories. DRIFT, by contrast, is more a travelogue. The place lore is the mind of Elizabeth Lowe.

DRIFT can be found online at: www.framethink.org

Leave a Comment