SEA SPACE

8-minute film

by William Farley

What is it about travel, about being carried along, that stimulates the memory and causes stories to spill out of us with the urgency of a deathbed confession? On a long distance road trip with a friend, or someone you barely know, histories long ignored can emerge as if prompted by subtitles on the painted scroll of road unraveling ahead. Because one of you is driving, eye contact is limited, and a kind of mutual solitude reigns, out of which the stories roll with uncharacteristic ease in the privacy and confinement of that climate-controlled compartment rushing through air over land.

At sea, the same elements — motion, confinement and privacy — are at play, but in different proportions. At sea, you do not rush over a compliant roadway. Your vessel contends arduously with the belittling liquid undulations of the planet’s great oceanic immensity. Confinement, while more spacious, is more complete and lasts longer — no quick stops for gas and a bite to eat. Nothing is quick. And, if you’re not traveling for pleasure, the company you keep is close, fixed and not of your choosing.

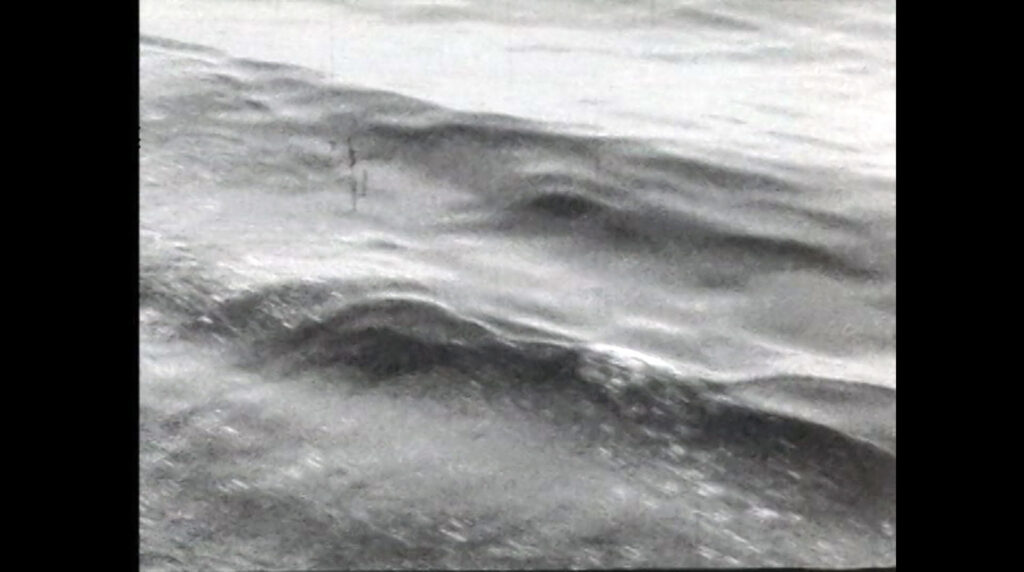

For a time, way back in the last century, filmmaker William Farley shipped out as an Ordinary Seaman on cargo vessels. Aboard a ship that sailed out of New Jersey, went south, through the Panama Canal and across the Pacific, he shot some 16mm film and made sound recordings on audio cassettes. The result was an understated, low tech, and beautiful series of grainy black and white images that spoke to the experience of being at sea. The film’s sound, underlain like a hidden treasure, was a dialogue between the filmmaker and a fellow crew member that you had to strain like an eavesdropper to make out.

This was, as I remember, it, Sea Space, 8 minutes of art that changed forever my way of thinking about film. Sea Space expanded the range of what I could expect from film. I had relied on “the movies” to amuse or inform, linear presentations that told a story or explained things directly. The subtle atmospherics of Farley’s images —water rocking to and fro in a metal sink, the sea horizon through a porthole rising and dropping out of sight— spoke eloquently but obliquely of the rhythmic monotony of seafaring without resorting to prosaic shots of sailors on watch or manning the helm.

The viewer could be forgiven for not picking up exactly what the filmmaker and a crew member were saying off camera, but, for listening carefully, one’s reward was a weird, dark and shocking tale. Taken together, sound and image conjoined into a sensory whole that lingered in the film’s aftermath, much as the mind crafts a memory-picture of an abstract painting, saves the most memorable lines of a word-bending poem, accepts the logic defying sense of a dream.

Oh, but memory can be a trickster. A camera records what it sees. A tape recorder records what it hears. But the mind is a storyteller, recording and then interpreting and remembering not the recording but the interpretation. Having tracked down Sea Space after a hiatus of decades, I was shocked to find that the conversation in its soundtrack is captioned on screen in the film as it currently exists. Recently, I asked Farley if these captions had always been there. He said he was “pretty sure” they had been, and it’s really not for me to convince him otherwise.

Sea Space is, after all, Farley’s memoir, within which is a seaman’s confessional — also a memoir. In orbit around these memoirs is this little piece you are reading, which is in itself a loving memoir of the Sea Space that has long abided in my memory wherein it is not the seaman’s story but haunting snatches of it in accented English and Farley’s urgent questions in response that blur into a kind of verbal ambiance supporting, as would a musical soundtrack, the film’s moody images.

In light of this, it is curiously appropriate that the Sea Space soundtrack came into being as Seaman Farley stood watch and was recording some thoughts on cassette intended for his friend, the late Robert Ashley, composer and musical visionary who pioneered a concept of spoken word as music. Ashley coined the term, “New Narrative Opera” to describe this work. [See: “Private Parts: The Park and The Backyard” for starters.] So, there stands Farley on the ship’s foredeck talking to Robert Ashley when a shipmate approaches with a burdensome story to unload, drawn to Farley’s rolling tape like a moth to flame as the seascape, an impassive infinitude, stretches before the two of them. G&S

farleyfilm@gmail.com

Sea Space can be purchased on DVD at farleyfilm.com/sea-space

Leave a Comment