William James Aylward’s Three Views of American Clipper Ships in 19th-century New York

New York at that time was the clipper capital and her home was in South Street, the most fascinating place in the world. Never, since sea-borne commerce began was it so enthroned as here… The proud ships…once poked their bowsprits inquisitively across the street, almost into these very windows…[in] that decade between eighteen fifty and sixty.

—W. J. Aylward, “The Clipper-Ship and her

Seamen,” 1917[1]

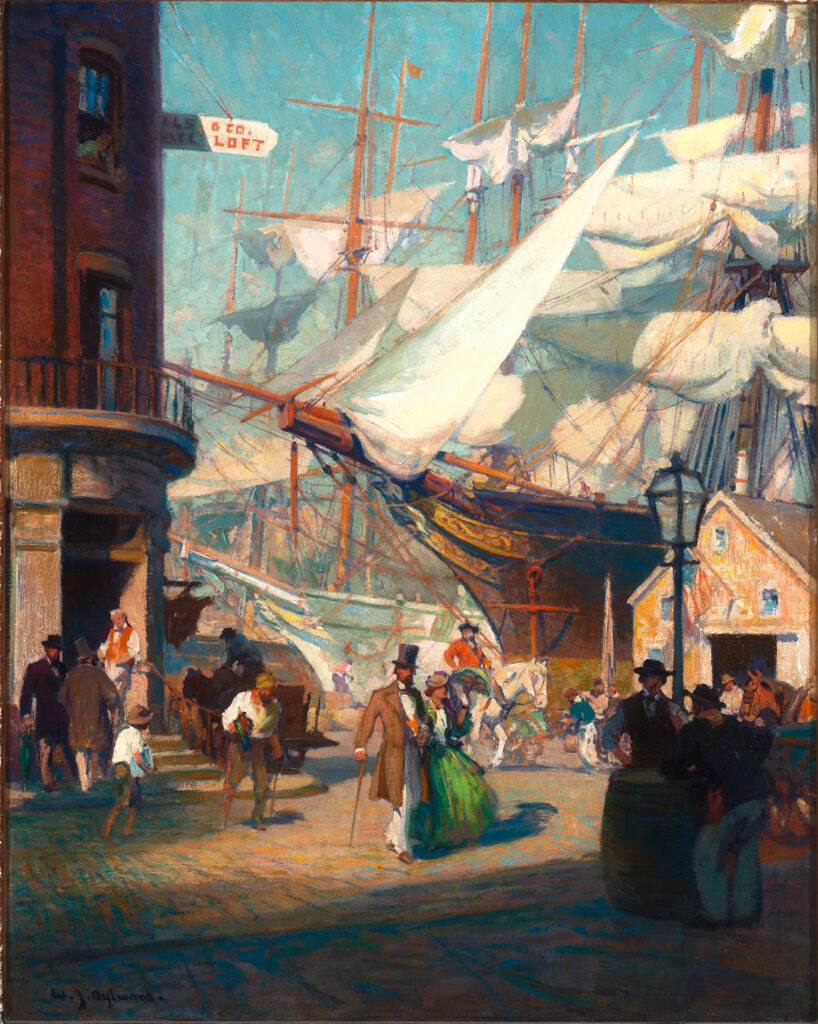

Why would an artist paint three versions of a scene? This question arose for me recently when the Delaware Art Museum received the gift of an oil painting of Manhattan’s South Street Seaport by William James Aylward (1875–1956). Facing the East River before it empties into Upper New York Bay, the South Street district was the center of America’s international maritime trade in the mid-19th century.

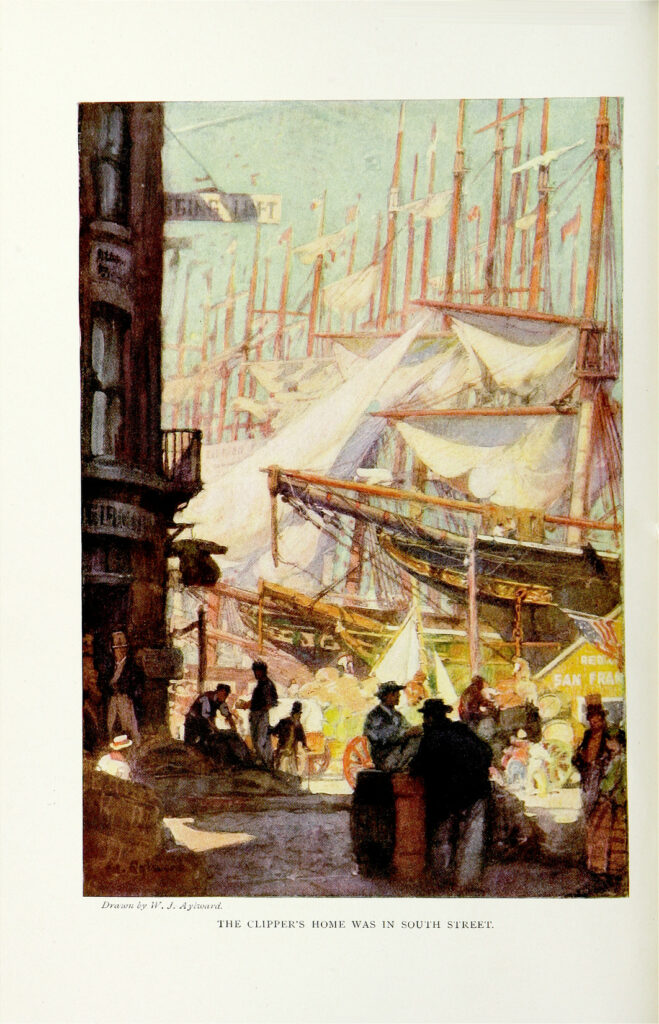

The oil painting (figure 1) is a variant of a watercolor by Aylward that the Museum purchased in 1934 (figure 2).[2] Both works are similar to Aylward’s illustration “The Clipper’s Home Was In South Street,” which appeared as the frontispiece of his article “The Clipper-Ship and Her Seamen” in the April 1917 issue of Scribner’s Magazine (figure 3).[3] We don’t know the current location of this work, which was probably an oil painting. It was one of Aylward’s 11 illustrations (two appeared in color) for his 16-page article. Scribner’s used the image again in 1931 with the title “Yankee Clippers at the South Street Dock, in Boston” in the section “American Shipbuilding Reaches its Height” in The United States of America: A History by Thomas Jefferson Wertenbaker and Donald E. Smith. In the 1917 magazine and 1931 book, the color is quite washed out compared to the two originals.

The placement of Aylward’s full color illustration as the frontispiece not just for the first article but for the issue indicates confidence that readers would value both. Editor Robert Bridges knew that “a brilliant, colorful image—worthy of framing—if you could bear tearing it out of the magazine…functioned as a beacon signaling the onset of the magazine’s high-quality material.”[4]

All three works—and Aylward’s

nostalgic narrative—invite us to “imagine ourselves back among the handsome

ships.” It’s likely that the watercolor was a study

for the donated oil painting, as these two share many compositional elements.

In addition, the watercolor’s graphite under-drawing indicates that the artist

was plotting basic forms and relationships. Aylward may have devised the

published Scribner’s version from the

donated oil painting that he had already created either for himself or for

another (now lost) publication or for a private commission. Both publishers and

collectors recognized Aylward as a marine artist; the ship’s diagram he holds

in a formal photograph announces his specialty (figure 4).

The donated oil painting was a wedding gift to the donor and her husband in 1951. It bears a partially obscured auction label, so it spent at least some time in the commercial realm. Or, possibly this apparently unpublished version came after the magazine piece, when Aylward was not tied to his article’s narrative.

Similar scenes with significant differences

The artist did not date any of the paintings, so we can’t tell their order of creation. Whatever their differences, the clipper ship is always the star. In each one, sharp prows and windswept sails dominate the center and more than half of the canvas. The three paintings offer individual stylistic effects and, as a result, different evocative moods.

The watercolor

The watercolor’s overall impression is of a sun-washed and spacious scene. The doorway to the building at the left is one of the few dark areas; translucent gray shadows in the foreground do not obscure the two men at a barrel in the lower right. Consistent with the painting’s probable function as a study, forms are broadly indicated. Aylward makes little attempt to delineate facial features or hands. Above, we see a mass of overlapping sails more than single ones. Clearly, Aylward’s primary interest is color. The woman’s bright green dress and yellow umbrella, the mounted rider’s red jacket, and the orange vest on the man in the doorway (perhaps a tavern-keeper) are focal points. The yellow and blue design on the nearest clipper’s hull is broadly painted but vivid.

The oil painting

In the oil painting, Aylward adds more and livelier color, dramatic lighting, and some new characters. Light and even shade are prismatic and intense. Deep shadows encompass the men and the barrel while creating a pavement of purple, blue, and green. At right, a draft horse now comes into clear view near a man framed by the building’s entrance. Ahead of them, another man dressed in blue and white pushes a wagon with a green box. The one-legged man’s package has become multi-colored, and the young boy’s is blue. At the doorway, a man has gained a green umbrella. Above, the onlooker is also in green, leaning from one of the windows that reflect the blue of the sky. The design on the rich brown wooden hull of the large clipper has grown into an interlace that changes colors in the shade of its sail. Brilliant sunshine fuses a mix of colors on the hull of the next ship, attended now by a man in pink shirt. Some sails are in shadow and some in full light. The nearest and most dazzling one blazes up and over the streetscape. Aylward highlights the elegant couple—illuminated on the polychromatic textured cobblestones—as they move from the sunlight toward deep shade. Her hat no longer matches her luminous skirt; she wears a straw hat with a band of small pink and purple flowers. And her green umbrella now has a decorative blue edge. Her top-hatted companion displays a glimpse of orange vest. This mere stroke of color typifies Aylward’s approach throughout, an approach that he carries over from the study even though the painting is much more finished. Shapes emerge from color, and color conveys form. He intends to give us the view that we would actually enjoy on this cloudless day: not portraits or particulars of the scene, but color and motion.

The Scribner’s Magazine published version

The quality of the reproduction puts Aylward’s Scribner’s image at a disadvantage. Still, it’s obvious that we are seeing a different view of the dock, or perhaps the dock on a different day.

Here Alyward uses fewer and busier figures and many more ship masts, the better to emphasize that this is a workplace. There is less space for strolling. The men at the barrel have moved in closer to the action. The mounted rider leans forward purposefully instead of relaxing in his saddle. Not one but three workers now appear under the balcony. Two well-dressed men—probably ship owners—still converse at left but the casual tavern-keeper has gone, as has the one-legged man. The arm-in-arm couple (identified in the article as a captain and his wife) arrive, cropped, in the right corner. She no longer wears an eye-catching green skirt. Almost an afterthought, they no longer encourage us to slow down and take in the atmosphere.

Other clues let us know that this is a place of business. No one looks informally out a window. The cut-off lettering on the building at right indicates San Francisco, a reminder of the clippers’ record-breaking voyages to deliver miners and supplies to the Gold Rush city. A chain for moving cargo hangs over vats stacked against the building. A prominent American flag reinforces the seaport’s role in the nation’s global trade. The illustration reflects Aylward’s description of the “noise and confusion of the busy street,” where walks “choked with bales of cordage and chain cables” echo with the “coarse banter and rough shouts” of stevedores. During its heyday, Aylward reminds us, the seaport district thronged with “riggers and block-makers and ship carvers and gilders,” along with shops offering “chronometers and compasses…sea-boots and oilskins…new sails, a spare anchor, and cable.” Hotels, taverns, and restaurants over-flowed with served workers, residents, and visitors.[5]

Superb specimens of marine architecture”

The “why?” of the three versions, and the chronological mystery, are really of less importance than Alyward’s goal in painting them: to illustrate clippers’ supremacy on their “swift flight from horizon to horizon.” He enlivens his nostalgic text with chronicles of seamen’s and the captains’ mastery of life aboard the “long, lean vessels with their rakish masts, yacht-like lines, and clouds of snowy canvas.”

With names like Flying Cloud, Lightning, and Witch of the Wave, clippers were made for speed, covering up to 400 nautical miles in 24 hours.[6] They dominated America’s international fleet from the 1840s until steamships outpaced them by the 1860s.[7] Sharpened prows and sterns along with three masts carrying as big a spread of sails as possible gave them their agility and velocity. Their lofty and complicated rigging required up to 60 men to operate.[8] In a period when rapidly increasing production of goods made America a regular trading partner of European and Asian nations, clippers carried exports and imports ranging from wheat and cotton to boots and barrels to wine and tea.[9] Some transported ice to tropical countries. In the late 1840s, the demand for miners and their supplies during the Gold Rush drove clippers to break speed records on their voyages from the Atlantic seaboard around the Cape of Good Hope to California.

Aylward recounts Flying Cloud’s 1851 passage from New York to San Francisco in a record-breaking 89 days and 21 hours, despite heavy gales interspersed with doldrums. In 1854, the clipper broke its own record by 13 hours. Although Aylward doesn’t mention the fact, an admiring California newspaper reporter (the first of many across the country) noted that

equally intriguing is the fact that the navigator was a woman—the Captain’s wife, Eleanor Creesy. Remarkable for being a functioning female member of the clipper’s crew, she was also an inspired navigator. Her skills are considered to be a major factor in the ship’s safe and swift passages. A native of Marblehead, Mass., Mrs. Creesy learned navigation from her father, a successful captain in the coastal schooner trade.[10]

The Creesys became national and eventually worldwide celebrities as they continued their global clipper voyages until their retirement in 1855.

The Artist

William James “Bill” Aylward formed his love of sailing as a youth in his native Milwaukee, where his father built and sailed Great Lakes ships.[11] He began his career with “ten years of drudgery at commercial work” in engraving houses in Milwaukee and Chicago. After courses at the Art Institute of Chicago and the Art Students League in New York, he entered illustrator Howard Pyle’s school in Wilmington, Delaware. He would later continue his studies privately while living and exhibiting in France. In 1904, he illustrated Jack London’s Sea-Wolf, with five paintings of drama on large and small ships in roiled waters.

In 1905, Pyle obtained permission from President Theodore Roosevelt, whom he had known since the late 1890s,[12] for Aylward to sail in a supply ship with the flotilla convoying the Dewey Drydock from Maryland to the Philippines. His illustrations of the journey across the Atlantic into the Mediterranean, through the Suez Canal, the Red Sea, and into the Indian Ocean to Luzon appeared in “The Sea Voyage of a Drydock” in Scribner’s Magazine.[13] He returned to San Francisco on a four-masted bark from Japan. Aylward’s reputation as a marine illustrator was established.

In 1914, a reporter visited Aylward’s studio in Glenridge, New Jersey, where she saw

models of every craft that ever sailed the oceans blue—whalers, brigs, schooners…and an ancient Spanish brigantine…(a)n old ship’s lantern…brass cannon…oars and anchors…old sea-trunks…naval and sea costumes…(and) canvases depicting the fight and crash of a naval battle, or a ship plunging through a choppy sea under full sail.[14]

In 1918, Aylward was one of eight artists (five were Pyle students) commissioned as captains in the Engineers Reserve Corps of General John J. Pershing’s American Expeditionary Force (figure 5).[15] The artists created on-scene images for war bond posters and other government publications designed to inspire citizens’ support of World War I. The works were also meant to preserve a visual record of the War.

Using his already-honed skills, Aylward depicted military activities at French ports. He also recorded often dreary and frequently sorrowful views of soldiers at headquarters and comrades’ gravesides. His drawings are sensitive to soldiers’ daily lives rather than merely propagandistic.[16]

After the war, Aylward resumed his

career, primarily as a magazine illustrator. His work appeared in Harper’s Magazine, The Saturday Evening Post, and The

American Magazine, among others. In 1925, he illustrated an edition of

Jules Verne’s Twenty

Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. During the1930s, he taught

at Pratt Industrial Art School and the Newark (NJ) School of Fine and Industrial

Art. In 1934, when the Delaware Art Museum bought the Seaport watercolor,

Aylward was living in Port Washington, New York, a community between Manhasset

Bay and Hempstead Bay on Long Island Sound. In 1950, at the age of 75, he wrote

Ships and How to Draw Them. Aylward

exhibited his work regularly throughout his career.

[1] W. J. Aylward, “The Clipper-Ship and her Seamen,” Scribner’s Magazine, vol. 61, no.4, April 1917, 403.

[2] The Delaware Art Museum houses about 4,000 works of American illustration art. The holdings have grown since 1912 from the founding collection of paintings and drawings by Howard Pyle (1853-1911), a leading American illustrator of books and magazines. Aylward studied with Pyle in the early 20th century.

[3] To see the reproduction in the magazine, see image 60 at: https://library.brown.edu/cds/repository2/repoman.php?verb=render&id=1252526867984375&view=pageturner&pageno=60

[4] “Scribner’s Magazine: An Introduction to the MJP Edition, 1910-1922,” by Mark Gaipa, The Modernist Journals Project: http://modjourn.org/render.php?id=mjp.2005.00.111&view=mjp_object Viewed June 22, 2019

[5] For an eyewitness overview of South Street Seaport’s commercial activities in the 1850s, see Thomas Floyd-Jones, Backward Glances: Reminiscences of an Old New-Yorker (New York, 1914), 7-9

[6] About 460 miles. The clipper derived its name from the verb “to clip” or move at a high speed, as in today’s expression moving “at a fast clip.” For a summary of the history and types of clipper ships, see Howard Chappelle, Clipper Ships”: http://www.uscommunityindex.com/clippers/museum/ms_clipp.htm

[7] Clipper shipbuilding continued in Great Britain through the 1870s, primarily to serve the tea trade from China. See Chappelle, ibid.

[8] Aylward does not mention the race of sailors, and all those he illustrates are White. For discussion of the possibly 20-25% of American seamen through the mid-19th century who were Black, see W. Jeffrey Bolster, Black Jacks: African American Seamen in the Age of Sail (Cambridge, MA, and London: Harvard University Press, 1997). See also an interview with Bloster: http://www.seacoastnh.com/black-jacks/

[9] It should be noted that many of the goods traded by the United States during the period, especially cotton, were produced, either directly or indirectly, by enslaved people.

[10]See “Eleanor Creesy,”in A World of her Own: 24 Amazing Women Explorers and Adventurers, by Michael Elson Ross (Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2014), 112-118

[11] Biographical material from “William James Aylward, 1875-1956,” by Phyllis J. Nixon, in A Small School of Art: The Students of Howard Pyle, Rowland Elzea and Elizabeth H. Hawkes, editors (Wilmington: Delaware Art Museum, 1980), 18

[12] Ian Schoenherr, “A Birthday Card for Theodore Roosevelt,” Howard Pyle (blog), October 27, 2014:

[13] Scribner’s Magazine, vol. XLI, no. 5, May 1907: https://www.unz.com/print/Scribners-1907may-00513/

[14] “The Picturesque Suburban Studios of Famous Artists,” by Lucy B. Jerome, The Countryside Magazine, December 1914, 304-305: https://books.google.com/books?id=MzAwAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA305&lpg=PA305&dq=%22depicting+the+fight+and+crash+of+a+naval+battle,+or+a+ship+plunging%22&source=bl&ots=-bC99XGaHS&sig=ACfU3U2RLcvutDTKN19kHJ9AL6ygkspIwA&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjqxIbso_biAhUKnlkKHWeEBQEQ6AEwAHoECAAQAQ#v=onepage&q=%22depicting%20the%20fight%20and%20crash%20of%20a%20naval%20battle%2C%20or%20a%20ship%20plunging%22&f=false

[15] National Archives. The Unwritten Record. World War I Combat Artists—William James Aylward. Janet Hodges and Gene Burkett. August 22, 2014. See https://unwritten-record.blogs.archives.gov/2014/08/22/wwi-art-of-william-james-aylward/

[16] For examples of Aylward’s war drawings, see National Archives / The Unwritten Record: World War I Combat Artists—William James Aylward, by Gene Burkett and Jan Hodges at https://unwritten-record.blogs.archives.gov/2014/08/22/wwi-art-of-william-james-aylward/; Prints and Posters / Army Art of World War I at https://history.army.mil/html/artphoto/pripos/wwi1.html; and Alfred Emile Cornebise, Art from the Trenches (College Station TX: Texas A & M Press, 1991), 70-76 at https://books.google.com/books?id=g77YBQAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=william+aylward+ships+and+how+to+draw+them&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjMhPiZmvbiAhWkm-AKHbeJCToQ6AEISzAI#v=onepage&q&f=false

Leave a Comment