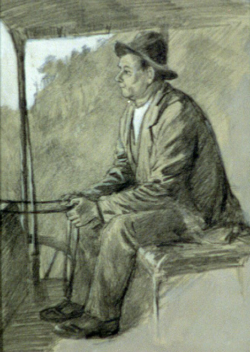

Uncle Sam / an old driver. By Howard Pyle (1853-1911). Graphite, charcoal, and gouache on paper. For “The Old National Pike,” by William H. Rideing, in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, November 1879. Pages 801-816. 11 15/16 × 9 inches. Museum Purchase, 1919. DAM 1919-2

Pyle’s small picture shows “Uncle Sam” in his retirement at Hagerstown, Maryland, after his working for years as a wagon driver on the National Pike. I’ve always found this to be an unusually life-like and engaging portrait—the relaxed pose and conversational gesture, the level gaze, an apron suggesting some recent tasks, and a hat on the window sill implying outdoor activities. The man radiates a spirit that makes you want to know more about him. I recently decided to explore “Uncle Sam”—Samuel Nimmy—beyond the report given in the article that Pyle illustrated. A little research revealed that his story, insofar as our limited information goes, is fascinating in its narrative and frustrating in its incompleteness. A fuller picture of Nimmy and his life requires some background and a little imagination.

Harper’s article on “The Old National Pike”

In 1879, Harper’s New Monthly Magazine commissioned 26-year-old Howard Pyle to illustrate W. H. Rideing’s article “The Old National Pike.” Rideing (1853–1918) was a journalist who frequently wrote travel reports for Harper’s. Readers would have recognized the title as a reference to the route officially named the National Road. Approved for construction by President Thomas Jefferson in 1806, the National Pike was the first federally funded highway. Building began in 1811 at Cumberland, Maryland, and ended at Vandalia (then the capital of Ohio) when the government ran out of money as a result of the Panic of 1837. The 620-mile route followed old buffalo paths and Native American trails across the Alleghenies and connected the Potomac and Ohio Rivers. Originally a highway of dirt, rocks, and wood, the road was hailed as an engineering triumph. By the 1830s, the federal government ceded control of the road to the states through which it passed. To ensure maintenance and paving, the states made it a toll-road, or turnpike. From the beginning, the National Pike served as a major gateway to the West for settlers, commodities, and mail. Its importance declined mid-century with the advent of the railroad. In the 20th century, the automobile brought about its revival as US Route 40.

By 1879, the road was derelict—“a glory departed,” according to Rideing—and a good subject for a nostalgic travelogue. He laments the Pike’s overgrown areas and imagines sociable gatherings of travelers at now-abandoned inns. To give readers a sense of the Pike’s once-thriving commerce and energetic travelers, he interviewed a few men who had worked as drivers of wagons and stagecoaches. “Aroused out of the dreamy silence of their ebbing days,” Rideing says, they told of encounters with statesmen such as Andrew Jackson on his way to Washington, “excellent cookery” at fine taverns, and the “tonic air of the pines.” The old witnesses admitted that robbers on the highway were sometimes a menace, but the drivers were adept with their own weapons. Rivalries among drivers often added some drama. All in all, Rideing concludes, friendly residents of picturesque villages along the way helped foster the drivers’ camaraderie on their working journeys. Although Rideing doesn’t mention racial barriers, Black and White drivers had separate overnight quarters and dining areas.

Pyle’s Illustrations

Pyle’s 12 illustrations mixed imagined scenes, such as townspeople honoring Andrew Jackson during his 1828 run for the Presidency, with the ruins of a brick tavern along the part of the road that he and Rideing could still travel on. Pyle’s illustration of Leander, their hired horse-drawn carriage driver for part of the trip, was one of three portraits he created for the article. The image reflects Rideing’s account of Leander as a rather introverted companion.

Leander. By Howard Pyle, (1853-1911). Pencil and wash on paper. For “The Old National Pike,” by William H. Rideing, in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, November 1879. Cabinet of American illustration, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. https://www.loc.gov/item/2010717443/

At Hagerstown, Pyle and Rideing meet Samuel Nimmy:

He lives in a comfortable cottage at Hagerstown; the walls of his parlor are hung with certificates of membership in various societies and with various patriotic chromos; the center table is loaded with books, principally on negro emancipation and the events of the Civil War.

Nimmy entertains his guests with stories about how he kept his team of horses healthy and fended off marauders who lurked in the woods along the trail. He also tells the visitors that he raised a company of volunteers during the Civil War and founded a group called the Sons of Freedom. When the latter organization was accused of harboring escapees on the Underground Railroad, Nimmy was vindicated and acclaimed by his community at the outcome. Nimmy’s parting words to Rideing and Pyle are “Gentlemen, remember the date—August 29, 1793,” a proud reference to his birth date.

Rideing’s describes Nimmy’s “grandiose” speech, revealing his skepticism toward all the old drivers who recall their exploits—possibly exaggerated—during the “golden age” of the Pike.

Another survivor of the old “Pike” is Samuel Nimmy—a patriarchal African who “played tambourine” for General Jackson, and drove on the road for many years. He is an odd mixture of shrewdness, intelligence, and egotism. His recollections are vivid and detailed…and he describes his experiences in a grandiose manner that is occasionally made delicious by solecisms, or sudden lapses into negro colloquialisms.

Rideing’s patronizing reference to Nimmy’s grammar would probably have mirrored the reaction of many Harper’s readers.

Who was Samuel Nimmy?

Two publications give us a sense of Nimmy’s accomplishments and stature in his community. A social announcement in Hagerstown’s The Herald and Torch Light, on July 1, 1868, noted:

[A procession by] the colored Masons of this town, together with a number of their brethren from other places marched in Hagerstown. The Chief Marshal was Samuel Nimmy. They made quite a creditable appearance, marching well and observing all the rules of decorum which impart respect and dignity to such occasions.

His death notice in The Hagerstown Mail, on 12 August 1881, reported:

Death of one of the oldest. Samuel Nimmy…who to many generations has been known as “Uncle Sam,” and who was a patriarch and leader in all social and political matters among his colored brethren, died at his home on Bethel Street last week and was buried with all the honors which could be bestowed upon his memory by his brethren in various organizations, on Tuesday last. He was the founder of several benevolent orders and a man of great energy even in his old days. His portrait and biography figured recently in Harper’s magazine, in an article descriptive of the “National Road,” and he had reaped the ripe old age of 95 years.[i]

If Nimmy were correct in citing his birthday in 1793, and his specificity makes this seem likely, he would have been 88 at his death (not 95), and 86 when Rideing and Pyle met him.

In Nimmy’s recollections of his days as a driver, he doesn’t mention the years he worked or on what parts of the Pike he drove. He would have been 18 when the road opened in 1811. By the end of Civil War, when he was 72, traffic had diminished considerably. Given his references to “General” Andrew Jackson (who did not become President until 1829), we can reasonably assume that Nimmy was driving on the Pike at least during the road’s heyday in the1820s when it was celebrated in popular songs and poems. It seems unlikely that he would have worked into his 70s (in the 1860s) but, if he did, he would have been aware of the Battle of Antietam and other conflicts along the Pike. In any case, it was a demanding profession with long hours, in all weather, over hilly (and sometimes icy) terrain, caring for teams of horses pulling loads of over 6,000 pounds. Overnight quarters for wagon drivers (and their horses) at inns along the way were fairly meager.

Pyle’s illustration of Nimmy aligns with the self-confident demeanor referred to in the few public references to him. Rideing’s description of Nimmy’s history books about the African American experience implies literacy and engagement with the world around him, even in old age.

It appears that Nimmy was never enslaved, although he lived in a state where slavery was legal. Maryland was a border state (that is, it had legal slavery but did not join the Confederacy). It did not end slavery until late 1864, almost two years after the Emancipation Proclamation, which affected only Confederate states. By the time of Nimmy’s birth in the 1790s, many African Americans in Maryland were free: many had been emancipated by their former “masters” and others were of mixed race, traditionally regarded in Maryland as “free persons of color.”

Daily Life on the Old National Pike

In Charles Fenno Hoffman’s book A Winter in the West / by a New Yorker (1835), he described the assortment of travelers that Nimmy could have observed on his route:

As for the emigrants, it would astonish you to witness how they get along. A covered one-horse wagon generally contains the whole worldly substance of a family consisting not un-frequently of a dozen members… The strength of the poor [horse] is…half the time unequal to the demand upon it, and you will, therefore, unless it be raining very hard, rarely see anyone in the wagon, except perhaps some child overtaken by sickness, or a mother nursing a young infant. The head of the family walks by the horse, cheering and encouraging him on his way.

Single men [pedestrians] have a cloth knapsack…hung across their backs, and are often very decently dressed in a blue coat, gray trousers, and round hat.

[Men on horseback] almost invariably wear a drab great-coat, fur cap, and green cloth leggings; and [carry]… a pair of well-filled saddle-bags.

The females…ride in short dresses. They are generally wholly unattended, and sometimes in large parties of their own sex. The saddles and housings of their horses are very gay… with saddles of purple velvet, reposing on scarlet saddle-cloths, worked with orange-colored borders… The effect of these gay colors, as you catch a glimpse of them afar off, fluttering through the woods, is by no means bad.

He described the goods wagons like those Nimmy would have driven:

…The leading horses are often ornamented with a number of bells suspended from a square raised frame-work over their collars, originally adopted to warn these lumbering machines of each other’s approach, and prevent their being brought up all standing in the narrow parts of the road.

One of Nimmy’s memories centers on a nighttime attempted robbery by armed highwaymen that alarmed his passengers until he safely delivered them to a tavern. However, in Thomas B. Searight’s book The Old Pike: A History of the National Road (1894), he states that “there were Negro wagoners [wagon drivers] on the road, but Negro stage drivers were unknown.” He took this, and all his information from “persons in any manner and at any time identified with the road, whether by residence or occupation and without regard to age, race, color or condition of servitude.” Still, Searight was writing in 1894, a full 25 years after the Pike was active, so some memories may have been imprecise. If Nimmy was, in fact, referring to driving a stagecoach, the “rule” about the segregation of drivers may not have been strictly followed.

When Nimmy was at the reins of a wagon, he may have had passengers that Rideing doesn’t allude to in his comments about travelers on the Pike. In fact, the road was a well-traveled part of the Underground Railroad.

The National Pike and the Underground Railroad

The National Pike passed through Maryland (border state where slavery was legal until late 1864); Pennsylvania (free state); West Virginia (became a state in 1863; slavery ended early 1865); and the free states of Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois.

Rideing fails to relate a sight which Samuel Nimmy certainly would have seen on his route as enslaved people were transported across state lines for sale. Searight describes a witness’s report:

… for be it remembered that Negro slaves were frequently seen on the National Road. The writer has seen them driven over the Road arranged in couples and fastened to a long, thick rope or cable, like horses. This may seem incredible to a majority of persons now living along the Road, but it is true, and was a very common sight in the early history of the Road and evoked no expression of surprise, or words of censure. Such was the temper of the times.

Another witness recorded:

…runaway slaves…lurked along its edges, crept for shelter under its S bridges and burrowed in hay lofts of stage barns.

Nimmy’s fellow driver John Deets of Uniontown, Pennsylvania remembered “scores of slaves…handcuffed and tied two and two to a rope that was extended some 40 or 50 feet, one on each side.”

Tensions must have run high on the Pike, not just for those escaping slavery but for those Black and White residents who risked secretly giving them transport, food, shelter, and directions. Federal fugitive-slave laws guaranteed slaveholders the right to recover enslaved people. By 1850, private citizens of free states were obliged to capture and return fugitive slaves, a law which encouraged people to hunt down and capture escapees for bounty. Those who aided escaping slaves could be fined at least $500. The Pike’s four counties in Pennsylvania provided especially important stations on the Underground Railroad. In the 1820s, the state legislature passed laws that gave some protection to Pennsylvanians who assisted fugitives, directly contradicting federal law. Still, slave hunters were tenacious.

As the Pike approached Wheeling, West Virginia, the stakes escalated for enslaved people traveling as prisoners of slave traders. Wheeling was the site of weekly slave auctions from which people were sold “down the river” and put on Ohio River barges bound for the Deep South.[ii]

Nimmy’s ample freight wagon could have provided hidden compartments for escapees. It’s hard to imagine that Nimmy, even given the little we know about him, would not have tried to assist such fugitives. It’s been suggested that the separate tables and sleeping quarters for African American drivers in the Pike’s taverns might have allowed escapees to blend in with them as they pursued their journey to freedom. This, and other strategies, might have allowed Nimmy—judged intelligent and shrewd by Rideing in his one conversation—to transport and protect those fleeing captivity. It’s easy to imagine Nimmy in league with other drivers in devising ways to move desperate, and largely defenseless, people toward freedom. Rideing also notes that Nimmy spoke in “measured sentences for a long time without hesitating.” Familiar with the Pike’s geography and surroundings, he sounds like a man who could confidently take some risks. And like one whose quick thinking could work his way into opportune situations (and out of dangerous ones), and help others to do the same.

“Uncle Sam”

As far as I know, Pyle left no record of his feelings about his trip along the National Pike or his time with Samuel Nimmy. He may, however, have held the subject in special affection or respect. It’s the only one of the 3 portraits (in fact, of the 12 illustrations) that he signed.

Mary F. Holahan PhD., Curator of Illustration

This article first appeared on the Delaware Art Museum Blog.

[i] There are discrepancies in references to Nimmy’s birth year. The death notice states that Nimmy was born in 1793 and died at 95 in 1881. If he were 95 in 1881, he would have been born in 1786. A birth year of “c. 1797” appears in the 1870 US census, which cites the birthplace as Washington County, Maryland. Nimmy told Rideing in 1879 that was born in 1793, which would make him 86 at the time of the interview and 88 at his death.

[ii] Lakshmi Gandhi, Code Switch: Word Watch. What Does “Sold Down The River Really Mean? The Answer Isn’t Pretty. January 27, 2014 https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2014/01/27/265421504/what-does-sold-down-the-river-really-mean-the-answer-isnt-pretty

Sources:

The African-American Experience in Southwestern PA. National Park Service, U. S. Department of the Interior, Fort Necessity National Battlefield Park https://www.nps.gov/fone/planyourvisit/upload/FONE%20African%20HistorySiteB_NBl_pc.pdf

Lakshmi Gandhi, Code Switch: Word Watch. What Does “Sold Down The River Really Mean? The Answer Isn’t Pretty. January 27, 2014 https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2014/01/27/265421504/what-does-sold-down-the-river-really-mean-the-answer-isnt-pretty

John A. Grant, Garrett County and The Underground Railroad, Western Maryland’s History Library: http://www.whilbr.org/itemdetail.aspx?idEntry=3102

The Historical Marker Database. https://www.hmdb.org/results.asp?SeriesID=16

Historic National Road. https://www.visitmaryland.org/scenic-byways/historic-national-road

Charles Fenno Hoffman. A Winter in the West by a New-Yorker In Two Volumes (New Yoork: Harper and Brothers, 1835) https://books.google.com/books?id=n6bhAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA9&source=gbs_toc_r&cad=3#v=onepage&q&f=false

Thomas Mainwaring, Abandoned Tracks, The Underground Railroad in Washington County, Pennsylvania (Notre Dame Press, 2018) https://books.google.com/books?id=ALtXDwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=The+Underground+Railroad+in+Washington+County,+Pennsylvania,+by++W.+Thomas+Mainwaring&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjQjKPEzf_fAhUoZN8KHWQ8D9wQ6AEIKDAA#v=onepage&q=The%20Underground%20Railroad%20in%20Washington%20County%2C%20Pennsylvania%2C%20by%20%20W.%20Thomas%20Mainwaring&f=false

The National Road in Song and Story. Compiled by the Workers of the Writers Program of the Work Projects Administration in the State of Ohio: https://archive.org/stream/nationalroadinso00writ/nationalroadinso00writ_djvu.txt

Thomas Brownfield Searight, The Old Pike: A History of the National Road (Uniontown PA; published by the author, 1894): https://books.google.com/books?id=-LZCAAAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=the+old+pike+searight&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwin3NTdgYLgAhXsY98KHUotBAcQ6AEILTAB#v=onepage&q=the%20old%20pike%20searight&f=fals

Leave a Comment