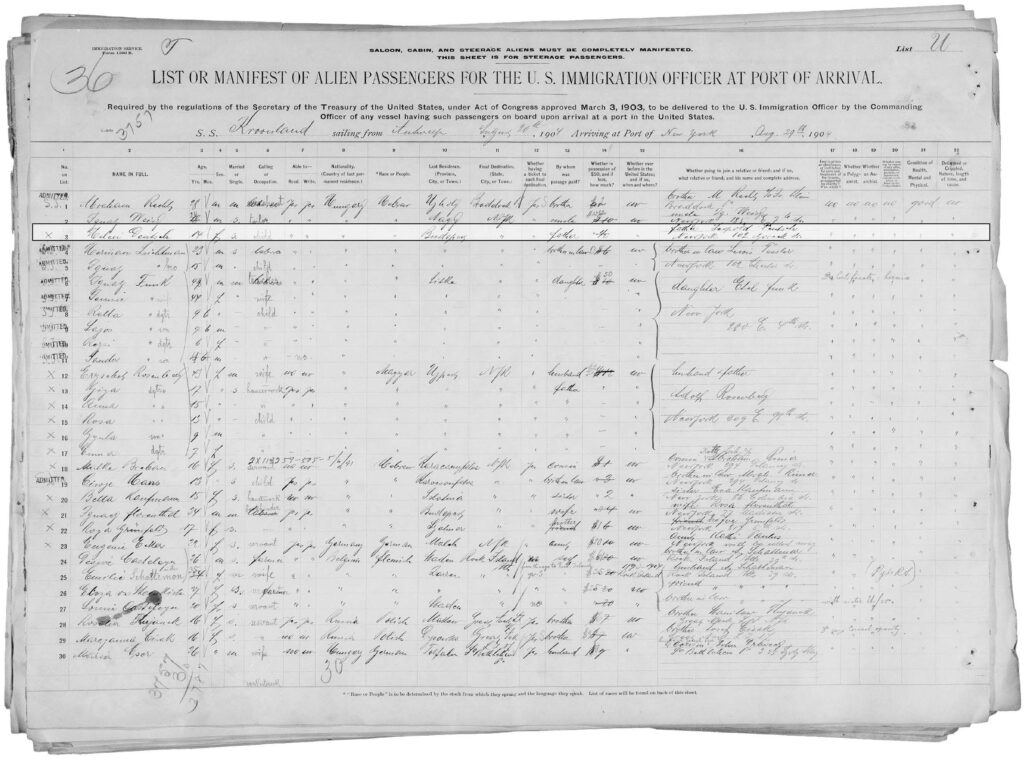

Excerpts from Helen Klein Breiner’s Journals

My family left Hungary for America in 1904. But for me, it wasn’t meant to be. On the train to the ship, we had to stop in Vienna, and everybody had to pass an eye exam for the disease trachoma. That’s where I was separated from my family. As we were boarding, the ship’s doctor told my mother, ‘Helen won’t be able to go with you. She has trachoma.’ He told her she should leave me there in the hospital in Vienna and that they would cure it. Otherwise, I would be blind in three months. It was strange because I could see okay and my eyes didn’t hurt. And my mother—you can imagine how she must have felt—she didn’t want to let me stay in Vienna, in the hospital.

She said, ‘No! I have a brother in Budapest, I’m going to send her there and they’ll take care of her.’ So, I don’t know how they got in touch—it must have been by telegram. They must have sent a telegram that I was going back, that they should wait for me at the railroad station. And that’s the way it happened. I went back to Budapest by myself on the train and my family got on the boat and went the other way to America. That was 69 years ago. I was thirteen years old.

“My uncle had kids, and they all treated me well, like I was one of their own. I waited six months before my family was able to make enough money to buy a ticket for me to travel alone. Finally, it came.

“My aunt packed up some food for me to eat on the train trip from Budapest to Antwerp where the boat left for America. She prepared a roast duck and made cookies. She put it all together in one big package with my clothes, including the pretty pink dress my sister, Rose, had made for me in Budapest as a present

for working in our family’s matzoh factory. Before Passover, every room became part of the matzoh factory. When she gave it to me, I said, ‘Oh this is so pretty. I’m not going to wear it until I get home to America. I always called America ‘home.’

“I couldn’t open the package from my aunt when I was on the train because I was too nervous to eat. I just sat there, rigid. I didn’t even blink my eyes. I shouldn’t go to sleep and miss my stop. I kept my eyes open for three days until the time came to change trains in Belgium. And then Antwerp. And I still didn’t sleep or eat.

“As soon as I got on the ship, I started looking for a family. I was in Steerage, and I was scared to be alone. I saw a family with little children, boys, girls, man, wife. I went over to them, and I said, ‘Oh please, I’ll do anything. I’ll help you with the children. Just please let me stay with you in your room.’ The mother said, ‘Oh, I have trouble of my own, I have enough to do with my own family. I’m sorry.’ Then I tried another cabin. A Russian family. But the same thing: I couldn’t stay there.

I didn’t speak Russian, just Hungarian and Yiddish but I understood No. Finally, I went to a third woman with kids, and she said, ‘Okay, stay here.’ And that’s the way it was. She took from me two bottles of liquor that my uncle sent for my mother. He was in the wholesale liquor business. She said, ‘Why do you need that bottle, so give it to me.’ I was glad to give her anything as long as she didn’t ask me for money, which I didn’t have. I helped her. I took care of the kids while she took a nap or something. She needed me as much as I needed her.

“Finally, I felt safe enough to eat. I hadn’t eaten in three days. That’s when I finally opened my package that my aunt prepared for me with the roast duck and cookies and my pink dress. That’s when I saw—it was August and it had been very hot in the train and three days wrapped up and tied up in a bundle, when I opened that package it was alive! Worms were crawling all over my dress, —whatever I had, the roast duck and lemons and cookies, the stockings, the change of clothing…

“I just lifted the whole bundle and threw it over the railing into the ocean. My pretty pink dress went with it. All I had was a navy-blue sailor dress I had on, and I had a straw hat with a ribbon hanging down the back. And that’s what I wore for nine days on the ship without a change.

“The whole way from Hungary to America, the whole time I was on the train and the boat in Vienna and Germany and Belgium and Antwerp—wherever they stopped they always did eye examinations, and I managed to avoid them. I just hid behind the luggage outside every port. Everybody went in for the exam and I was always outside hiding. I was small and they didn’t notice me. Nobody did. I never took even one eye exam! And I got away with it!

“I remember the night before we got to New York Harbor. Everyone went up to the deck and they were pointing and cheering, ‘That’s Ellis Island! That’s Ellis Island!’ They were so excited. I just wanted to see my family.

“When I got off the boat, they took me into a building, and they put me in a cage. Like an animal I was, in a wire cage! And there I had to wait until my sister, Rose, the one who made the pink dress for me, and my brother, Louis, came to redeem me. They had come to America with my family when I wasn’t allowed to get on the ship. And my sister said, ‘Where is your luggage, where is evertthing?’ You were supposed to have $10 to go through immigration. I heard if someone had it they would go through and then pass the $10 bill to the person behind them in the line and the same $10 bill would go all the way down the line. If you didn’t have that you needed to have something valuable. I told her what I did with it, that I threw it overboard. So she took off a ring from her finger and put it on me and gave me her pocketbook. She was always so wonderful to me. So, I had something, and I went through immigration.

“I went home with them, my brother and sister. To my parent’s house—they all lived together on the lower east side of Manhattan where all the greenhorns came. I remember going into the apartment. Everyone was crying and laughing and shouting things. They were so happy to see me. Except my father was praying so he didn’t even look up until he finished. Then he hugged me and said he was never going to let go.” G&S

Excerpts from Helen Klein Breiner’s Journals edited by Roberta Schine

Leave a Comment