The summer of 1816 was an unusual one. The warmth and sunlight promised by European summer was replaced with days of rain, fog, and even frost after Mount Tambora’s eruption in Indonesia the previous year. Resulting global weather anomalies led to “the year without a summer.” Traveling throughout Europe despite the strange weather was notorious poet Lord Byron. A literary sensation in his lifetime, Byron was also famous for his indulgent, flamboyant lifestyle of racking up debts and engaging in dramatic affairs and scandals, earning public disapproval. While this made him the ideal Romantic anti-hero, it was also the cause of his self-imposed exile from England in the wake of his rumored affair with his own half-sister in 1816.

In a suburb of Geneva, Villa Diodati offered a quiet slice of Swiss beauty to Lord Byron from June to November that year. He traveled with his personal physician John Polidori and was soon joined by fellow English poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, Percy’s soon-to-be wife Mary, and her stepsister Claire. It was at Claire’s insistence that the Shelleys joined Byron on this trip; she’d had an affair with him and, possibly unbeknownst to her, was pregnant with his child.

The grim weather kept the group stuck indoors and settled into their moods. They read from Fantasmagoriana, a French anthology of German ghost stories, late into the night and discussed the limits of modern medicine, whether or not a corpse could be reanimated after death. When Lord Byron suggested a competition to see who could write the best ghost story, no one could have foretold the impact its results would have in literature and culture over the centuries.

It’s well known among readers that this friendly competition led to the groundbreaking Frankenstein from the mind of eighteen-year-old Mary. What is less well known, however, is that this competition also led to the creation of the vampire archetype that inspired Bram Stoker’s Dracula nearly 80 years later. This story was written by the non-writer within the group—John Polidori.

As the son of an Italian writer and publisher, Polidori shunned his literary aspirations in favor of following his father’s wishes to pursue medicine. At 21, he took the opportunity to travel Europe as Byron’s personal physician; unbeknownst to the poet, Polidori was being paid by Byron’s publisher to keep a diary of his travels with the notorious figure. It’s understandable that Polidori was sensitive to his role in the group—on the periphery, the “hired help” who hadn’t earned his way into the group by friendship, literary merit, or aristocratic ties—and he was known to have envied the literary success of the others even as he admired them. That, combined with Byron’s humiliations of the doctor, making him the butt of his jokes in front of his fellow “elites,” created a complex dynamic between the two. When the challenge to write a ghost story was set, the group laughed at Polidori’s initial idea. Perhaps this, along with every other slight endured (perceived or genuine) at Byron’s hand fueled Polidori’s desire to write something that would impress—and perhaps also fueled a clever bit of literary revenge.

Polidori took inspiration from a fragment of a story Byron had begun on this trip but never finished. Later published, Byron’s A Fragment of a Novel lays the foundation for a tale with supernatural, seemingly vampiric, elements. It requires no stretch of the imagination to wonder if Byron shared his work with the group, and having abandoned it, sparked an idea in Polidori’s mind. He wrote his novella, The Vampyre, that summer and made an impact that would echo in literature and culture for centuries—though he’d never know it in his own time.

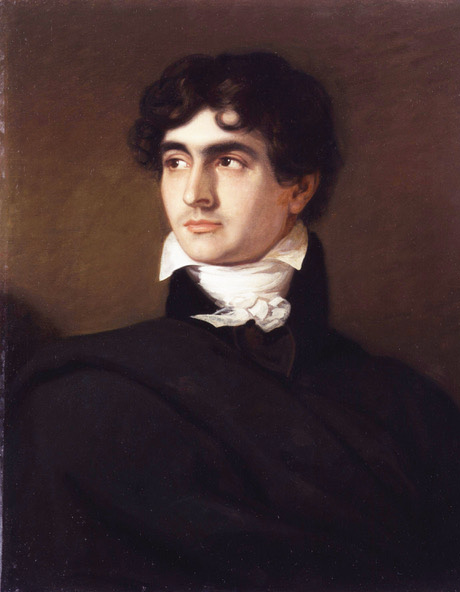

The Vampyre was the first prose vampire story in European literature, only predated by two epic poems about vampires from 1748 and 1801. This novella created the concept of Romantic gothic vampire fiction and the vampire archetype still popular across media. Before Polidori, vampires were thought of as shuffling, half-rotted, zombie-like creatures who rose from their graves to feed on the innocent. Polidori brought the vampire from the wild landscapes of European folklore into the very society of his readership, turning the creature into an English gentleman inspired by none other than Lord Byron himself.

Witty, charismatic, and undeniably talented, Byron was also arrogant, callous, cynical, and selfish. Polidori took what he thought of Lord Byron to an extreme and made him a parasite on the page. The sophisticated, alluring, amoral aristocrat had a place in society’s most fashionable drawing rooms, but lived selfishly and “fed” on those around him (specifically women) without care for the consequences. Polidori didn’t even attempt to conceal his inspiration; he named the vampire Lord Ruthven—the same name as the Byron-inspired character in a novel by Lady Caroline Lamb, one of Byron’s scorned lovers who called him “bad, mad, and very dangerous to know.”

The Vampyre was published in 1819. The manuscript, along with outlines of other works from the group on the Geneva trip, had been left with a countess Polidori had befriended during that summer. Obtained by another acquaintance of the countess as “a great favour,” they were sent to the The New Monthly Magazine where the editor mistakenly attributed The Vampyre to Lord Byron.

The public loved it, and the magazine editor arranged for its publication as a book soon after. Byron denied writing it and Polidori rushed to claim authorship, but the impact had been made. The edition that was in the process of being published was done so without Byron’s name, but also without Polidori’s. It was too late—the public had attributed the story to Byron and continued to do so despite the correction. Initial positive response and sales were largely due to Byron’s name; after claiming it as his own, Polidori saw little success.

Polidori’s life never righted itself after working for Byron and writing The Vampyre. He’d also written Ernestus Berchtold: Or, the Modern Oedipus, but his literary career was tainted by the disaster of The Vampyre’s original publication. He faced accusations of plagiarism and using Lord Byron’s name to further his own career. Even after having abandoned his literary aspirations, he couldn’t return to college to pursue alternative paths because the leadership didn’t approve of his having written The Vampyre. After racking up gambling debts and suffering an accident that left him with a brain injury, John Polidori passed away at the age of 25. While the official cause of death was ruled natural, he was believed to have taken his own life through cyanide poisoning.

When Polidori died, Byron bestowed a final indignity upon him, writing: “Poor Polidori, it seems that disappointment was the cause of this rash act. He had entertained too sanguine hopes of literary fame.”

Overshadowed by Lord Byron in life, John Polidori never quite escaped him in death, even once recognized as The Vampyre’s true author. Lord Byron’s name evokes the grandeur of the Romantic movement. Though Byron’s impact in literature is not to be understated, everyone—readers and non-readers, intellectuals and the everyman—is familiar with the impact of John Polidori’s work despite not knowing his name. Everyone knows the aristocratic, alluring vampire. While many may assume it originated with Dracula, Stoker built on the foundation Polidori had laid.

A grim summer sparked ideas in great minds that gave us defining pillars of Gothic literature. Their origin stories cannot be separated from Lord Byron. The Vampyre would not exist if not for him. Not just his suggestion of the writing competition, not just for his Fragment of a Novel, but him. He who inspired the world’s idea of a vampire with his arrogance and casual cruelty made an unintentional impact in literature and culture that eclipsed that of his own work with the passage of time. Poor Polidori, indeed. G&S

houseofcadmus.com IG:@houseofcadmus

Leave a Comment