Max Beckmann: The Formative Years, 1915-1925,” an exhibition at the Neue Galerie, is a show for our times. With unflinching realism, the artist’s focus is the aftermath of World War 1, which he called “an idiotic war.” The show covers the ten-year period when Beckmann’s style moved away from his Impressionistic 19th century modes and moved to fiercely dramatic realism.

The brutality of the war transformed this versatile artist, sculptor, printmaker. In a letter quoted in the Neue Galerie catalog Beckmann (1884-1950) writes: “What was really unhealthy and disgusting before the war was that business interests and a mania for success and influence had infected all of us in one form or another. Well, we have had four years of staring into the stupid face of horror.”

After a brief period serving as first a nurse and then a medic, Beckmann had a nervous breakdown and was discharged from service in 1917. That marked the end of his military career and his old style of history painting. He embarked on a new path, a concentration on contemporary subjects often combined with religious imagery.

His post World War I subjects were often what we today would call “woke.” His work is full of the evils of his time: poverty, political chaos, and social injustice. His romantic paintings of pre-war years were replaced with angular forms, images stuffed to the brim of the picture frame. His colors became stronger, his subjects more violent and grim.

Beckmann was now inspired by dreams, myths, fables and religious imagery. He loathed explaining his work and refused any type of analysis. During this interwar period, his paintings are suffused with his memories of the horrors of war. The world he paints is full of evil, pathos, and misery with few exceptions.

As a young art student, Beckmann married fellow art student Minna Tube whom he divorced in 1925 when he was 40. He fell in love with a young opera singer,

the socially connected Mathilde “Quappi” von Kaulbach. Together they lived in Germany where his work was regularly featured in exhibitions. After the Nazis opened the Degenerative Art exhibition in Munich where his work was harshly criticized, a demoralized Beckmann and Quappi settled in Amsterdam.

In 1947, they moved to the United States where Beckmann had obtained several teaching positions, eventually settling in an apartment in New York City. After the artist died in 1950, Quappi, an elegant, handsome, fashionable woman, lived in their apartment for the next 36 years, protecting and expanding her husband’s, by then prominent, legacy.

One of most poignant paintings in this compelling show is a portrait of Elsbet Götz, an attractive woman with very fine features, the daughter of a bourgeois family. Beckmann depicts her with hands folded with an enigmatic look on her face. It was the time of troubles for Jewish families and she would eventually be sent to Auschwitz where she would be murdered. He finished the portrait which he painted before the war after the armistice.

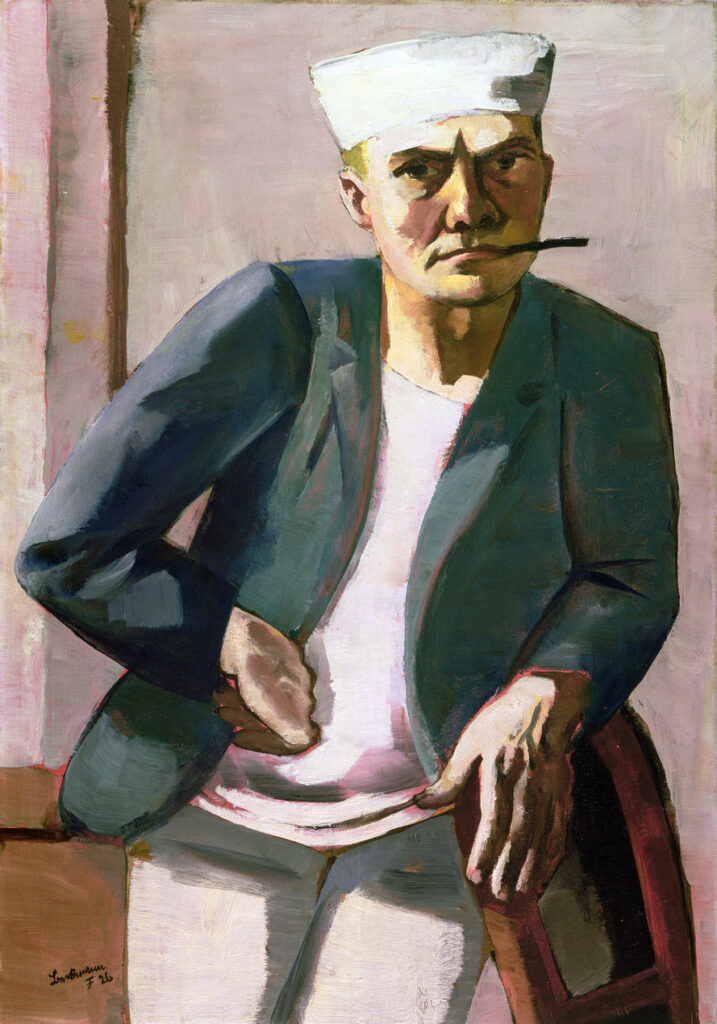

Another is Self-portrait with White Cap (1926) where the artist portrays himself as a sailor wearing a white hat and pants and a slate blue jacket. It was painted in 1926 after his honeymoon with Quappi on the Italian Riviera. The palette is much lighter than other paintings of this era. The artist looks grim, not exactly frowning. He stares at the viewer with an unlit cigarillo clamped in his mouth looking as if he carries all the woes of the world on his shoulders. It is one of 85 self-portraits Beckmann painted during his lifetime.

The Bark is a 1926 painting the artist dubbed “not at all offensive and very amusing.” Here we see the culmination of his new approach—stacking figures one on top of another squeezed into an elongated format.

In Descent from the Cross, the image of a gaunt Christ is compressed within the frame. There is no breathing space. It is a mix of naturalism and surrealism, all crammed into an elongated space. The body of Christ, bruised and skeletal, dominates.

In one of his many writings and diaries the artist attempts to explain his approach to art: “My heart beats more for a rougher, commoner, more vulgar art… one that offers direct access to the terrible, the crude, the magnificent, the ordinary, the grotesque and the banal in life. An art that can always be right there for us, in the realist things of life.” This manifesto prevailed in all his work until he died of a heart attack in New York City walking to see one of his paintings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. G&S

Leave a Comment