When I say the name Brontë to you, what do you think of? Well, if you ever took a high school or college British Literature class, you would probably respond with Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights or Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre. And if you were in a class more recently, you might even mention “the other sister” Anne Brontë and her novel The Tenant of Wildfell Hall. And even if you’ve never read any of the books—thanks to Turner Classic Movies and Amazon Prime among other venues—you might be familiar with the numerous film versions of Emily and Charlotte’s novels and the Masterpiece Theater rendition of Anne’s.

But when you dig a little deeper you discover more: There was the drunken brother Branwell (1817-1848) who never quite made it either as a painter or poet—and both Anne (1820–1849) and Charlotte ( 1816-1855) wrote other novels that are now being re-evaluated as classics of the Romantic Period: Agnes Gray by Anne and three more by Charlotte: Villette, Shirley, and The Professor. To top that, the poetry of Emily (1818-1848) is now considered some of the finest of the mid-19th century and is included in most major literature anthologies.

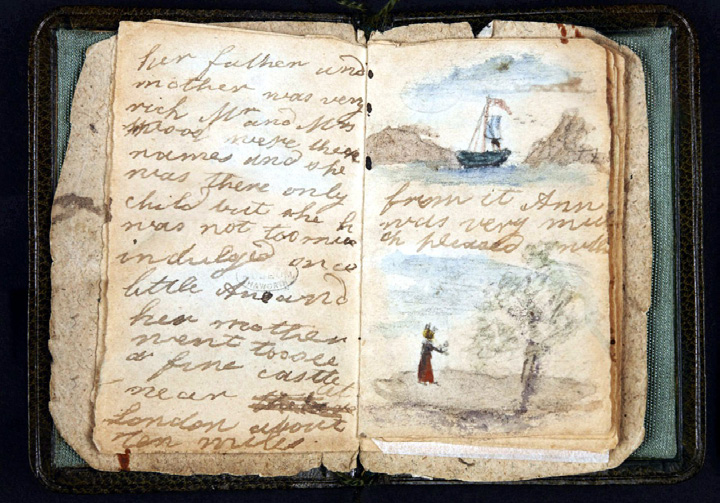

Yet there are two other sides to the three sisters and the errant brother that most people aren’t aware of. From the time the four siblings were little children, they began creating fantasy worlds that they wrote about—and illustrated—in copious detail. The stories about these mythological kingdoms—Gondal, Angria, and Glass Town—were written down in miniature notebooks of their own making. Today, many of these tales are available in lovely editions—and the original notebooks are museum pieces and collector treasures garnering auction prices near or above a million dollars.

The other side is their artwork. From the 1820s until their premature deaths from tuberculosis (Anne at 29, Emily at 30, and Branwell at 31) and severe complications during pregnancy (Charlotte at 38), the four siblings—especially the three sisters—produced some truly remarkable drawings, watercolors, and (in Branwell’s case) paintings.

Branwell’s work never went very far—his alcohol and drug addiction made consistent work nearly impossible. Yet some early pieces are quite fine. For example, the nighttime setting of The Lonely Shepherd from 1839 is both mysterious and gothic. Further, its nearly impressionistic brushstrokes invoke a decidedly Turneresque appearance. Critics and scholars alike lament the “could-have-been” talent of this young man whose demons he was never able to overcome.

On the other hand, all three sisters developed wonderfully as artists. If they had been men and if they had chosen not to write—both implausible hypotheticals—all three would have most likely been able to hone fine careers as artists. But women artists like women writers had huge hurdles to overcome during the 19th century. Even the few exceptions—Rosa Bonheur, Elizabeth Jane Gardner Bouguereau, and Virginie Demont-Breton, for example—struggled against rampant chauvinist prejudice. So, although the three Brontë women eventually saw themselves primarily as writers, they also produced wonderful art, which became for them a second language—another way to express their feelings and ideas.

Anne’s medium was primarily pencil or charcoal. Her Country Lane drawing from 1836 is an excellent example. The attention to detail is remarkable; indeed, a close examination reveals that she rendered almost every single leaf on the vegetation both individually and with precision. And her Sunrise over Sea from 1839 shows her ongoing love for the ocean. This piece was possibly copied from—or inspired by— a contemporary print although there are certain aspects of the drawing that suggest she added imaginative touches. The details of the bird and sailboat shadows, for example, show her keen eye.

Charlotte’s work was done in several media. One of her most highly regarded is her 1832 pastel drawing of the shepherd Lycidas, the focus of John Milton’s famous poem. What’s remarkable for many viewers is how easily one could see it as an Art Deco drawing from one hundred years later. The subtle blending of color, the rounded muscle forms, and the stylized facial features are beautifully rendered, and the body of the young shepherd is both lithe and sensual.

Emily also used pastels and charcoal, but her watercolor pieces—especially of the family dogs—are masterful. Her 1843 portrait of her sister Anne’s dog Flossy running across a field is full of life, and her 1838 watercolor and pencil rendering of her own dog named Keeper is detailed down to the individual hairs on the animal’s body. Anyone who knows about using watercolors knows that the execution of such fine detail—even with specially crafted brushes—is extremely difficult and time-consuming.

As the three sisters moved more and more into writing their novels by the mid-1840s, they kept producing art concurrently with that writing, and I submit that the on-going process of creating artwork informed the creation of their novels. The mindful way in which they noticed the world around them as artists became the equally mindful way in which they translated that world into words. Indeed, one picture was worth a thousand words—and those thousand words became pictures we can’t forget.

Sadly, Branwell’s all too brief forays into art and writing never took off because of the sledgehammer of addiction—and what we do have of his written and visual work is merely a tease. Thankfully we have the three sisters—and to read their fantasy juvenilia and—especially—to learn about and study their hundreds of drawings, pastels, and watercolors is to learn to read their seven novels in new ways with enlightened eyes. G&S

Dr. Bill Thierfelder

Lecturer, Artist, Writer (Portland, OR) Visiting Docent, American Museum of Natural History (NYC)

www. makingwings.net

Leave a Comment