And other Shenanigans, from an Artist’s Perspective.

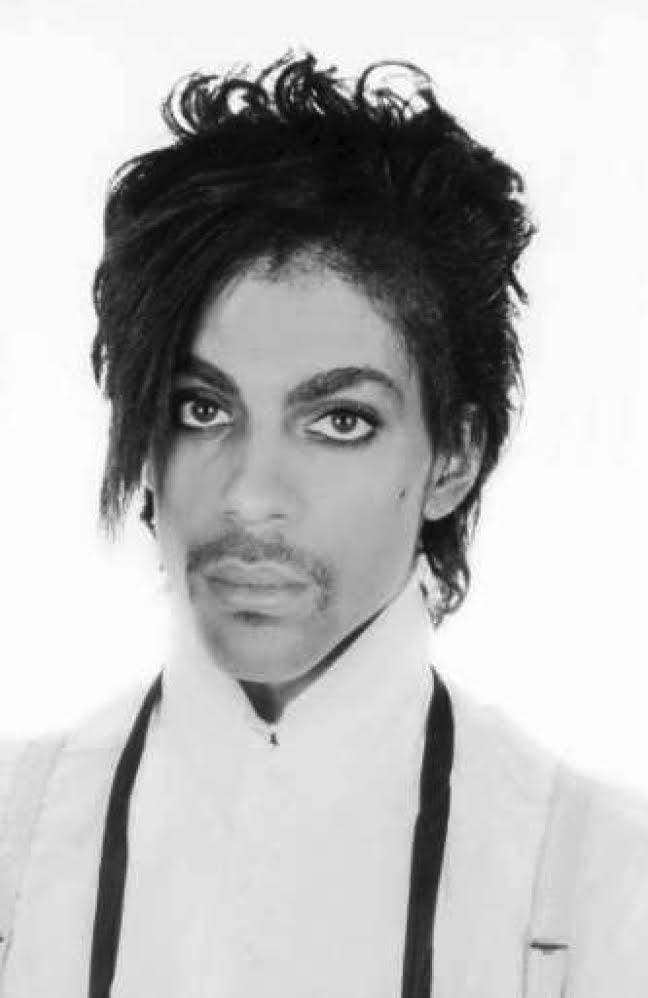

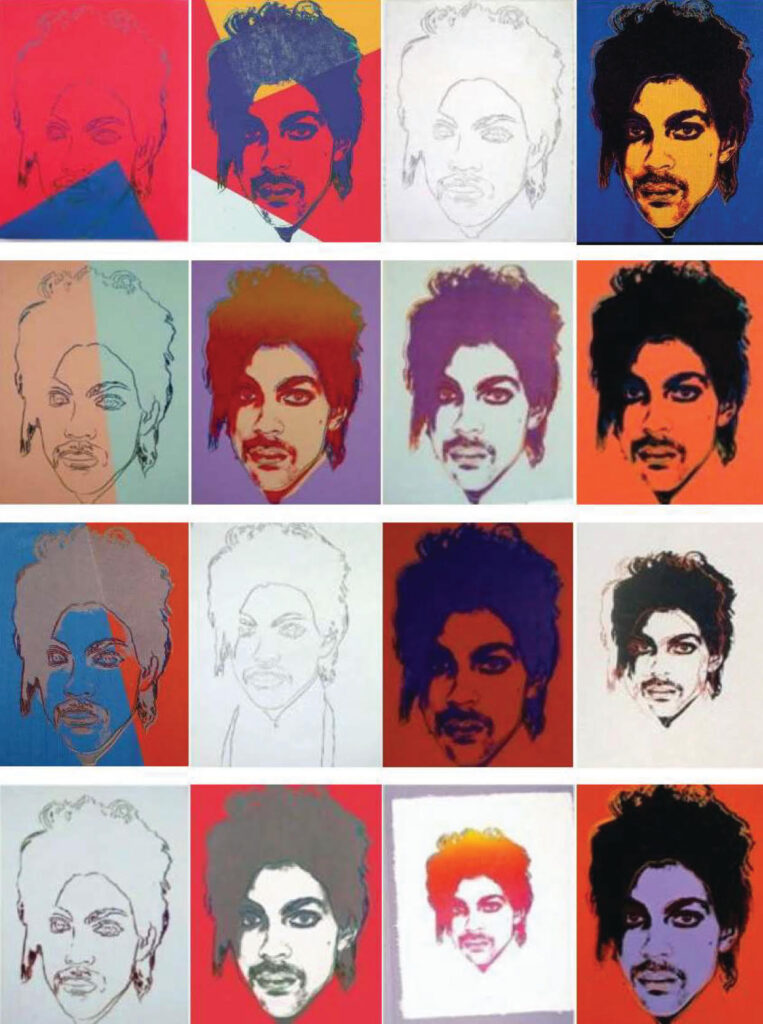

The recent Supreme Court case, Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, held that the Andy Warhol Foundation (“AWF”) did not meet the “fair use” requirements of 17 U.S.C §107, and therefore violated the copyright protections afforded to Lynn Goldsmith under 17 U.S.C §106, when it licensed “Orange Prince” to Conde Nast for $10,000.

This decision elicited a plethora of commentary from the art community, which seems to have developed an interest in statutory interpretation almost overnight. Legal analysis certainly has an allure, and it is possible that one or two fine arts majors regretted never taking a law class in school after this case was published—after all, many lawyers, perhaps including Justice Kagan, will confidently provide an in-depth art analysis to anyone who asks, or sometimes even to those who do not ask.

However, it is also possible that the myriad of opinions on the ramifications of the AWF case, ostensibly centered on a legal interpretation of the relevant statute, are actually purely artistic interpretations couched, often inelegantly, in legalese. The AWF case brings up many interesting and important issues; both legal and artistic. The artistic issues are probably better, and more completely fleshed out through a strictly artistic analysis.

For anyone still interested in the legal issues, I suggest reading the actual opinion. It’s not that long, it’s quite well written, the analysis is top-notch, and the alternative is to have legal information filtered to you through the mind of an art-history major trying to make it as a journalist.

From an artistic standpoint, the crux of the AWF case is whether Andy Warhol transformed Lynn Goldsmith’s photograph in such a way that it could be called art (his art). In other words, is what Andy Warhol produced actually art? This is probably the question that draws the attention, and possibly the ire, of the art world; it’s the reason why so many people take an interest in this case.

The legal answer to this question requires statutory interpretation, including analysis of precedential case law, and it is doubtful too many people not in law school care enough to take on such an endeavor. The artistic answer to this question on the other hand, requires an exploration of the personal and fundamental question of “what is art?” and perhaps a visit back to the early 1960’s when Warhol first used “objects” not created by him. There are many people in the art world who are very willing, with feathers ruffled, indignant opinions and possibly a lot at stake financially, to care enough to take on that question.

It was in the early 1960’s when Warhol’s original practice, or sin, depending on your point of view, of using objects he did not himself create, as his art, began, Campbell’s Soup Cans and Brillo Boxes being two of his most famous pieces. It was at this point a novelty, and it was at this point that the art world had the opportunity to decide whether these “objects” were being transformed into art.

It is apparent from recent commentary that a not insignificant mass believes that artistic, and legal, challenge to the status of Warhol as an artist (in respect to certain pieces) is a modern invention; that the AWF case created new theories for this purpose. This however is not the case. Any theories challenging the status of Warhol’s productions as art, presented in the AWF case, should be thought of as resurrected rather than created.

One person who did not view Andy Warhol as an artist as far back as 1964 is James Harvey; the person who designed the Brillo box while working at a Madison Avenue design company. James Harvey was an abstract-expressionist artist, at night after he punched out of his day job at the design company. Unbeknownst to Mr. Harvey, Andy Warhol copied the Brillo Box exactly, after viewing the box in a grocery store and being “overcome with envy and a sense of beauty.” Mr. Harvey, as reported by Time Magazine, only learned that Warhol was selling an exact copy of the Brillo Box when, by chance, he attended a gallery selling them in New York in 1964. Mr. Harvey who toyed with the idea of suing Warhol, died an untimely death in 1965 at the age of 36. On his death bed, he refused to acknowledge that his Brillo Box was a work of art. Moreover, he further refused to admit that Warhol’s Brillo Box was a work of art. To him, Warhol’s box was, at best, an example of excellent design work, and at worst, nothing short of a defilement of the sanctity of art.

Mr. Harvey is of course not entitled to the final word on Warhol as an artist just because Warhol used his design. However, it would have been interesting to see the legal outcome of such a case. The current AWF case leaves the question of whether Warhol’s Brillo Box is art, undecided. (At least that is my reading of the opinion – and if you are not convinced you do not have to take my word for it, you can read it for yourself).

That a Supreme Court case leaves what many people hold to be a truth—that Andy Warhol pieces are art—undecided, is quite a statement in and of itself. But again, it is not a new creation. In the 1960’s, the idea of Warhol’s pieces being classified as art, or even as “his,” was very much in contention. Even today, art museums, such as MOMA and the Philadelphia Museum of Art, which house Warhol’s Brillo Boxes and Campbell’s Soup Cans, respectively, each acknowledge that whether these pieces are in fact art, is a fundamental question and not a certainty. (Each museum’s description of these pieces, highlights the uncertainty of their status as art). Given that these are prestigious art museums displaying these pieces, one may infer that, at least from the museum’s perspective, the answer is yes. However, these museums pose these questions for a reason; and it’s not because the answer is obvious.

Due to the financial aspect of Warhol (a lot of wealthy people have a lot of money invested in his productions) it is probably safe to assume that those with a vested financial interest will be quite protective of Warhol’s status as an original artist. (It seems likely that this was in fact the intention of the Andy Warhol Foundation, which actually sued Lynn Goldsmith for a declaratory judgment upon hearing of her belief of copyright infringement. They could have easily paid her the $10,000 or settled out of court instead). They likely will not engage in a fair discussion of whether Warhol’s pieces are in fact art. This is probably also true of journalists and art historians who have written extensively of Warhol, but never broached the question of whether his “art” is in fact art in the first place.

Ultimately it is for the viewer to consider, based on history, and more importantly their own sensibilities, whether Warhol’s creations are art. Perhaps Andy Warhol’s greatest contribution to the art world will end up being the fundamental question his work forces every viewer to grapple with: What is art? G&S

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES Syllabus ANDY WARHOL FOUNDATION FOR THE VISUAL ARTS, INC. v. GOLDSMITH ET AL. CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT No. 21–869.

Argued October 12, 2022—Decided May 18, 2023

Leave a Comment