If you look up the artist David Rosenak on any search engine, you will be challenged. There’s no outright biography to be found. Instead, you have to dig through several (often obscure) sources, and what you come up with are enticing tidbits.

What a lot of digging will reveal is that he was a part-time Office Support Specialist for the Portland Water Bureau (in Oregon); that he was included in an exhibition called Unorthodox at the Jewish Museum in New York City in 2015 (apparently detailed by his actor brother Max in an impossible-to-find short documentary); and that he’s been shown in three group shows in the last nine years. A 2009 news item tells us he has a second story studio above a laundromat; that he was raised in California; that his mother and sister were also artists (he keeps some of their pieces in his studio); and that he spends so much time on his paintings (only one or two a year) that he leaves many unfinished.

What seems to come across in all the research is an extremely private man who’s been an active painter for several decades—yet has kept nearly his entire body of work to himself in his home and studio (he didn’t want to part with it). Only within the last year did he make the decision to gift these paintings to the Portland Art Museum (PAM) where twenty-two of those remarkable pieces were on exhibit this summer in a show called Untitled (Plaid Pantry).

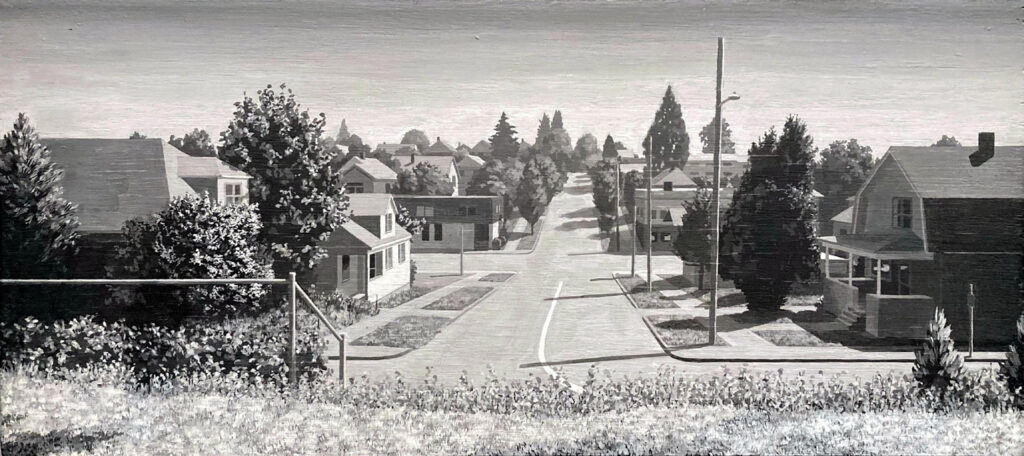

Those PAM paintings reveal several key things. Most obvious is the lack of any color. Every piece looks like a black and white photograph —or more accurately — a grayscale photo. Indeed, only until you get quite close do you see the meticulous brush strokes. It turns out that Rosenak was born color blind. His gray-dominant palette —which he adopted as a young man in Johnston College in Southern California —lets us see the world as he does.

Then there’s the size —with few exceptions, every painting is small. Several are only six or seven inches wide. We enter the physical smallness of the painting only to discover a whole world on the other side. One is perhaps reminded of Emily Dickinson living much of her life in the bedroom of her parents’ Amherst home while she created a universe full of truth in poems rarely more than a few stanzas long.

Next, you realize that every piece is rendered in acrylics on smooth plywood. The use of wood rather than a cloth canvas helps to enhance the “matte finish” photographic effect.

Then, there’s the subject matter. Almost every piece is a detailed observation of his workplace, home, or studio, providing an intimate connection to everyday things such as the speckled shadows cast from trees, the glimmer of a rain-covered street, the shadows of buildings on a sidewalk, or the pleasant glow of light emerging from a window in the early evening. We see sparse interiors, back porches, the local convenience store, and fenced-in backyards —almost all of them depictions of the Buckman neighborhood in Southeast Portland where he moved to in 1981. His is a quotidian universe.

Finally, you realize something else: Where are all the people? With the exception of an occasional solo figure or two in backyards or gardens, each of the worlds that Rosenak creates feels quiet and contemplative. These are not ominous post-apocalyptic scenes devoid of humanity; no, these are solitary, perhaps even lonely images that exude monk-like, Edward Hopper-like silence.

Quoted in a Portland Water Bureau newsletter in March of 2015, Rosenak says: “I’ve been making pretty much the same painting over and over for decades, trying to get a better result.” He also states: “My favorite paintings seize my mind

[and are] vivid yet mysterious[;] it’s like being eyeball-to-eyeball with a loved one. That’s the experience I’d like my work to provide a viewer and it’s best if I don’t interfere with words for what I don’t have words for.”

In a 2011 video interview that’s shown as part of the exhibit (it’s also available only after some deep online searching), Rosenak states that Persian and Indian miniature paintings were a major influence along with the brief, intense short stories of fellow Oregonian Raymond Carver. What we also learn is that he produces so few paintings a year partially because of his early onset Parkinson’s disease. Over time, with the failing use of his quivering right hand, he learned to use his left one with nearly equal dexterity.

What the interview also reveals is that rather than creating sketches for each painting, Rosenak often takes photos of his intended subject and sometimes combines multiple images meticulously. As a result, some of his paintings are a composite of several views melded into a single, imaginary image —which explains why one of the untitled paintings of his Portland neighborhood from 1996 contains “an incongruous orange grove and dirt road…grafted from memories of Southern California.”

While all of the untitled paintings —hence the title of the show: Untitled (Plaid Pantry) —are quite extraordinary, several stand out. One image (only 5.5 x 8 inches in size) is a scene of New York City (see front cover) painted in 1998; it was created from a photo that he took in 1980 when he was 23 years old. At the time he was staying in Chelsea, and the view shows what he saw looking east from West 28th Street and 10th Avenue. The beautiful baroque lines of the fence are juxtaposed with the cityscape beyond while the bare trees and the high, nearly invisible clouds create a cold, crisp sense of winter. What makes the painting unique is its subject matter. It’s the only image in the recent PAM show not depicting a neighborhood in Portland.

Looking at “Untitled” (1989-1991), we see the same focused detail. It’s a world in miniature—only 15 by 6.5 inches. You are putting your eye to a microscope and seeing a whole neighborhood. Rosenak states on the label copy: “Looking south on SE 25th [Avenue] from Lone Fir Cemetery along SE Morrison, This was [my] third or fourth cityscape and by far the smallest of my cityscapes.” Yet, the piece overflows with painstaking specificity.

His 1992 untitled painting depicting his shadow near his front porch door is particularly intriguing. As you enter the scene, you begin to realize that everything to either side of the center is tilted, creating a slightly “fisheye lens” effect. The porch on the left bends towards the street ever so slightly; and the door, window, and railing on the right tilt towards the barely visible backyard. Everything is subtly off-kilter.

So, yes, at first glance, each painting seems photorealistic; but a closer examination reveals subtle nuances of composition that remove the work from the realm of slavish reproduction. Each painting truly presents a parallel world. Things look familiar, but they are often eerily “other.” And it is that

“otherness” in the guise of the familiar that creates such a satisfying experience. G&S

portlandartmuseum.org

Leave a Comment