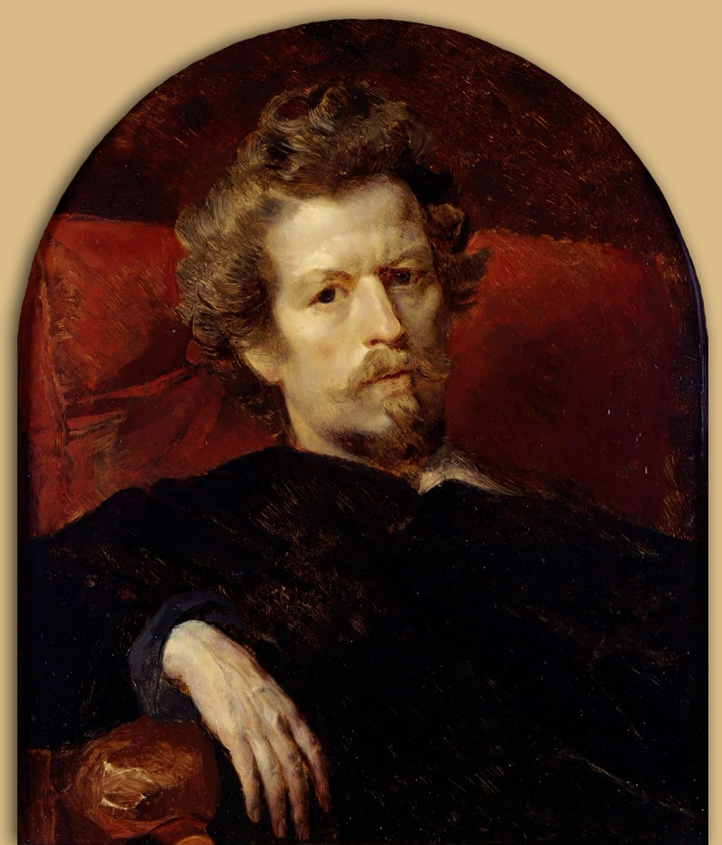

Our story starts with a painting, continues with a novel, and ends up as one of the most popular pieces of sculpture in the entire 19th century. Between 1830 and 1833, Karl Bryullov, a Russian artist who spent significant periods in Italy, produced a monumental canvas —measuring 15 by 21 feet in size—titled The Last Day of Pompeii, which depicts the horror caused by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE. From its first presentation, the work was seen as an important link between Neoclassicism— the predominant style in Russian painting at the time— and Romanticism— as it was being increasingly practiced in France and elsewhere on the Continent. The epic depiction of the mayhem and destruction was received to nearly universal acclaim and made Bryullov the first Russian painter to have an international reputation. Further, in Bryullov’s homeland, the painting was seen as proof that Russian art was as good as any art practiced in the rest of Europe.

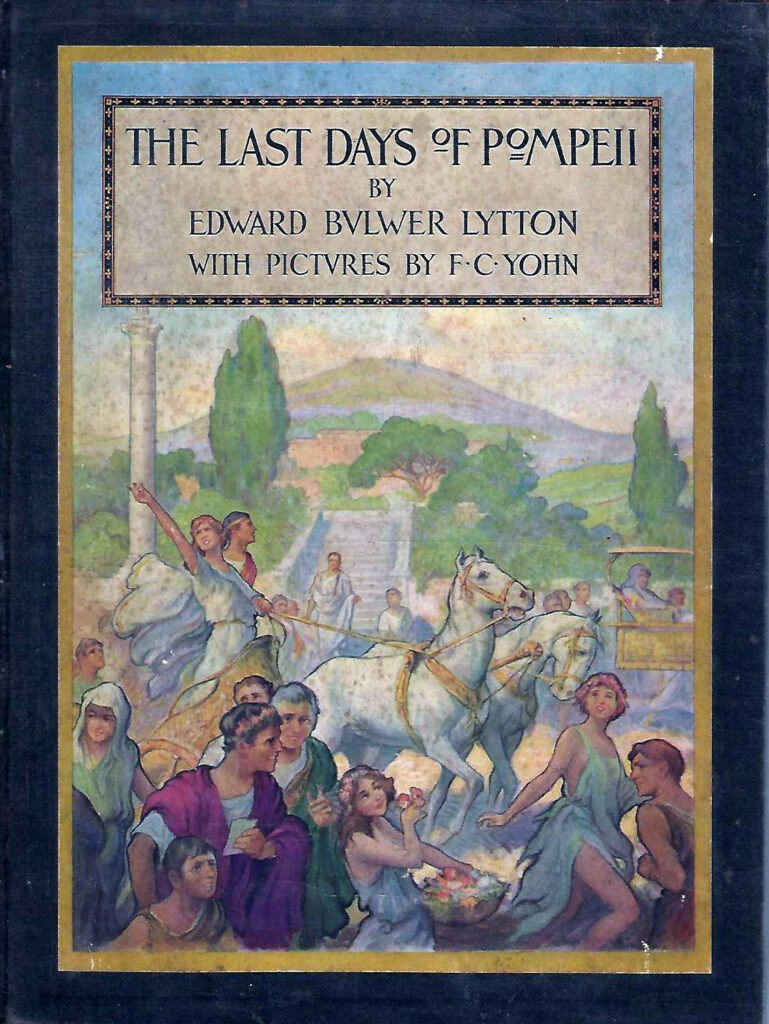

Yet that is only the start of our tale. Within a year of the painting’s first showing, the popular British novelist Edward Bulwer-Lytton (most famously known for the phrase “It was a dark and stormy night”) was inspired to create one of his better (and most remembered) works: The Last Days of Pompeii. Published in 1834, the novel uses its characters to contrast the decadence of 1st-century Rome with both older cultures and coming trends. The extremely melodramatic plot focuses on the Athenian nobleman Glaucus who arrives in the bustling town of nearly twenty thousand souls and quickly falls in love with a beautiful woman named Ione. As the tangled story unfolds, Nydia (a blind slave girl whom Glaucus has rescued) falls in love with the handsome protagonist. Unfortunately, Glaucus remains unaware of Nydia’s feelings. After extraordinary adventures— which include poisonings, gladiatorial fights, and witchcraft— Nydia leads Glaucus and his lover through the eruption of Vesuvius to safety on a ship in the Bay of Naples. She can do this because she is used to going about in utter darkness while sighted people are made helpless in the cloud of volcanic dust. The morning after the catastrophe, she commits suicide by quietly slipping into the sea, death being preferable to the agony of her unrequited love for Glaucus.

But that’s still not the end of our saga. We move forward about twenty years and meet the ex-pat American sculptor Randolph Rogers. Born in 1825 in upstate New York, young Rogers developed an interest in wood engraving, and in or around 1847 moved to work in New York City. Unfortunately, he had little luck finding employment as an engraver, so he ended up working as a clerk in a dry-goods store. Fortunately, his employers discovered his native talent as a sculptor and provided funds for him to travel to Italy. He began his studies in Florence in 1848 and was able to open his own studio in Rome in 1851, the city where he resided until his death in 1892.

At first, he devoted himself to creating statues of children and portrait busts of tourists. His efforts proved immediately successful —and lucrative. There was a slight hitch, however. Rogers was not happy working with marble, so all of his marble statues were copied in his studio by Italian artisans under his supervision from an original produced by him in another material, including plaster and clay. (Artists like Rodin slightly later in the century would do much the same, making fortunes from copies of originals, while Andy Warhol’s Factory was in some ways a 20th century incarnation of the concept.)

Rogers’ first large-scale work, Ruth Gleaning (1853), based on a figure in the Old Testament, proved extremely popular, and up to 20 marble replicas were produced by his studio. But then —after reading Bulwer-Lytton’s novel— Rogers decided to create his next large-scale work: Nydia, the Blind Flower Girl of Pompeii. Sculpted between 1853 and 1854, his sensitive depiction of Nydia proved even more popular than his sculpture of Ruth, and over the next three decades his studio produced at least 77 marble replicas in two sizes— a three foot version and a 4 and a half foot rendering. These stunning copies have since found their way into museums and private collections around the world, including the Metropolitan Museum in New York (where it stands guard at the entrance to the American Wing), the Portland Art Museum (where I first learned its multi-layered story), the National Gallery in Washington, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, to name just a few prestigious locations.

The label copy for the Metropolitan Museum’s version suggests that the statue is a superb example of “body language”—and indeed, that may be the best way to understand the success of the work. The very title tells the viewer that we are most likely in the midst of Pompeii’s final hours. Nydia’s closed eyes and her staff tell us that she’s blind. And though she leans her body forward urgently and her clothes are being blown by the volcanic wind, the real drama —and the success of this statue— is found in the simple gesture made by her hand. Body language. She raises her left hand to her right ear and listens for the clues that will allow her to bravely lead Ione and Glaucus out of harm’s way towards a boat in the Bay. She may be blind, but oh, she can hear better than most, and it’s that skill that allows her to be the hero when others fail. Ultimately this sculpture shows us the triumph of will, bravery, and adroitness over adversity; her selfless actions only prove how emotionally blind others have been. That Nydia in the novel later takes charge of her life by ending it (as Cleopatra and Queen Boudica had) is not to take away from her courageousness.

Rogers would go on to have other successes —including the creation of the 17-foot-high bronze doors depicting the exploits of Columbus that still grace the front of the United States Capitol building— but it’s the statue of a blind girl —inspired by a novel and a painting— that remains Rogers’ calling card today in dozens of collections around our country and beyond. G&S

Leave a Comment