When May DeViney comments about herself that “I am basically a cartoonist” and “Deep investigation is not warranted,” she is understating her originality. She does have a cartoonist’s ironic forthrightness, but closer examination, if not essential, reveals unexpected layers of meaning. Her “hint of the past…to express the continuity (persistence) of…underlying ideas” is both stylistic and thematic. Perceptions of centuries ago find expression in recycled fragments of our own time. She brings us into recognizable worlds that are suddenly unfamiliar. Like the discipline of “social studies,” with its universe of intertwined human activities, her works may leave us thoughtful, amused, unnerved, or ambivalent.

DeViney studied at the Art Institute of Chicago. She absorbed the impact of the Chicago Imagists, especially of her instructor Jim Nutt, a leading member of the Hairy Who collective, active from the late 1960s into the early 1980s. She veers away from the most exaggerated distortions, glaring color, and what one critic called the “madcap delirium” of those groups in favor of a more naturalistic style. Pop Art and Surrealism also have a presence in her work. DeViney’s lifelong involvement with social justice movements takes shape in much of her imagery.

Butcher Madonna is from DeViney’s “Working Saints” series, which “honors women’s hard and underappreciated work in supporting a better society… (and) questions whether a ‘perfect’ woman, such as the Madonna, would be viewed today as perfect, or have her every life choice criticized as women’s are today.”

Here the Madonna invites us to look at her unconventional work in a butcher shop or a slaughterhouse. Clean hands testify to her efficiency with a bloody cleaver. A blood stain on her apron suggests the cult of devotion to the Sacred Heart of Mary, a theological sign of her selfless love of humanity and her suffering over the death of Jesus. Instead of the usual serene dove representing the Holy Spirit, an upside-down plucked chicken hovers overhead, a comically undignified reminder of its earthly fate. There are no signs of the animals who have been sacrificed for human consumption. This interplay of symbols common in the history of Christian art provokes open-ended speculation.

Presentation of the haloed Madonna against a gold background wearing a traditional blue robe and veil is reminiscent of an icon. The balanced composition, solemn pose, and gesture of appeal make her both an object of reverence and a poster-like call to worldly action. Does the work she is doing bring her dignity or drudgery? Is she independent or a victim of exploitation? What is her role in the wider world? DeViney’s butcher challenges our society, including women, to probe the “perfect woman” model in all its complicated manifestations.

The word odalisque derives from Turkish. In 19th century France—when many Europeans traveled to the Near and Middle East—it came to mean a concubine in the women’s quarters (harems) in Sultans’ households. Men other than eunuchs were not permitted in harems, the residents of which included family members and enslaved women and girls. Some male European artists, including those who had never left the continent, developed a voyeuristic harem fantasy of mostly nude, young, submissive women on display and available to men. They painted them reclining amid luxuriant fabrics and opulence, wearing minimal jewelry and headpieces. The captives in these imaginary erotic settings—most famously those by Ingres, Renoir, and Matisse—were ordinarily given the White European features of the studio models.

In the flattened space of DeViney’s collage, the red-haired odalisque looks like a teenager. Behind her, an immense flower creates a suffocating, hothouse atmosphere. An assemblage of decorative objects, supported by an ornate 19th century chairback, comprises the background. The odalisque’s vulnerability and isolation are reinforced by her position as one among several ornaments. Wide-eyed, grinning men leer at her through a scrim-like “window.” An image of the Virgin Mary hangs near the center, an affecting suggestion that the girl may be praying for liberation. Sex trafficking and slavery in all its forms come to mind as modern reflections of the defenseless odalisque.

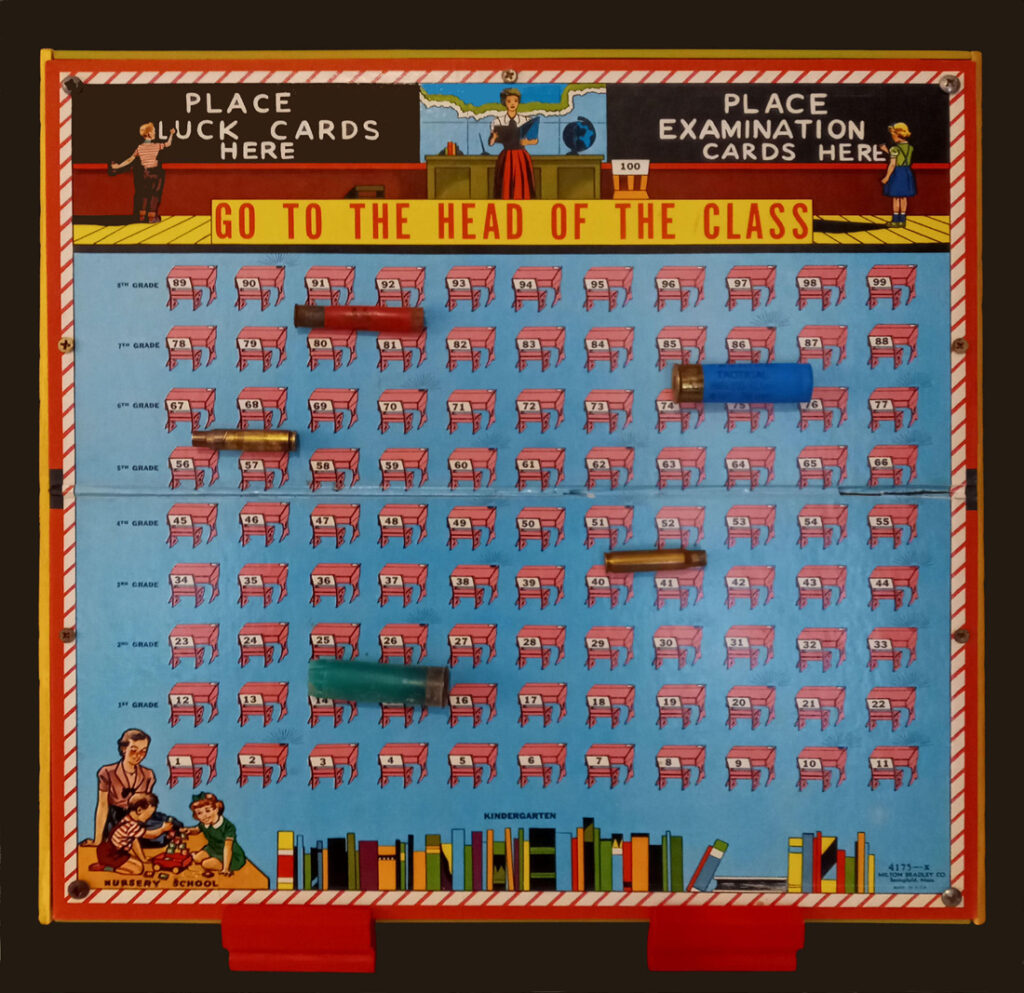

“Go to the Head of the Class” was a children’s board game produced from 1936 to 2013. Players answered questions with the objective of advancing up rows of desks; the first to reach the desk at the head of the class was the winner. The game involved both knowledge and chance, as some cards with random instructions moved players ahead or back. DeViney’s 1955 edition has a sky-blue background, colorful books, and characters typical of the Dick-and-Jane textbooks depicting White suburban children. A nursery school teacher oversees a smiling boy and girl in a corner, and the classroom teacher presides at her desk. The scene is a stereotypical paragon of the safe and orderly school room.

DeViney subverts this cheerful nostalgic atmosphere by adding “If they let you” to the game’s title. On the board, she put three crayon-colored empty shell casings and two shiny spent bullets like scattered toys that would block a player’s progress. But her baleful wordplay makes them ghastly evidence of the gun murders plaguing America’s schools. Aiming in different directions and randomly placed, they elicit now-familiar dread of unpredictable death. Mere luck may decide whether helpless children and their teachers live or die on any given day. DeViney notes that she looks at the spent ammunition and wonders what it was used for.

Art has always confronted social issues. DeViney’s artistic activism in causes ranging from women’s rights to a more sustainable environment to resistance to gun violence places her in a long tradition of protest art. Her mastery of history, seasoned by a sense of humor, creates highly personal but apprehensible works of art. Rather than tell us her solutions, she opens our eyes and minds to our own insights. G&S

© Mary F. Holahan 2023

Viridian Artists May 23- June 17, 2023 viridianartist.com

Leave a Comment