For many years, the Lutetia, the Grande Dame of the Left Bank, was our favorite hotel in Paris. For such a magnificent hotel the prices were something of a splurge, but affordable. Each time we stayed there we were overwhelmed by its beauty and the artwork, and we felt as if we were in a museum. An iconic landmark on the Left Bank, in the district of the ancient Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés, the Lutetia is an Art Déco palace. Although there are other famous luxury hotels in Paris, the Lutetia, named for the Gallo-Roman town that was centered on what is now the Ile de Cité, is unique for its rich and fascinating history.

Located on Boulevard Raspail in the 6th arrondissement, the Lutetia is noted for its architecture and its history, including its role as a headquarters of the German Abwehr (counter-espionage unit) during World War II. (Other luxury hotels were also ‘requisitioned’ by the Nazis, including Le Meurice, Le George V and the Ritz.) Among its many other 20th-century guests were André Gide, Samuel Beckett, Ernest Hemingway, James Joyce and family, Picasso, Matisse, Salvador Dali, Josephine Baker, William Carlos Williams, and Charles de Gaulle on his honeymoon (but we didn’t see any of them).

Le Bon Marché

Somewhat a surprise, the story of the Lutetia began across the little park it faces, known today as the Square Boucicaut. Long before the Lutetia opened in 1910, a novelty shop called Au Bon Marché (At the Good Market) was founded there in 1838 to sell lace, ribbons, mattresses and other assorted goods. Aristide Boucicaut, who worked there, had married a young woman named Marguerite Guérin who had a small shop nearby. In 1852 he became a partner in (now) Le Bon Marché, and he and Marguerite eventually bought the store. Together they amassed one of the greatest fortunes in France.

Boucicaut made drastic changes in the store’s operations, instituting fixed prices (instead of haggling) and guarantees that allowed exchanges and refunds, creating the first major department store in the world, upon which Macy’s, the Galeries Lafayette, Harrods, Marshall Field’s, Marks & Spencer and a myriad of other modern stores were modeled. He began to advertise and added a much wider variety of merchandise. In 1869 he built the first major building in the world designed to be a department store, and in 1872 he enlarged the store (with help from the engineering firm of Gustave Eiffel; thus there is a statue of “Gustave” in the lobby of the Lutetia).

Boucicaut was famous for his marketing innovations, including a reading room for husbands while their wives shopped; entertainment for children; and six million catalogs mailed to customers (long before Sears Roebuck began mailing catalogs in 1887). By 1880 half the employees were women. He died in 1877, and Marguerite ten years later, shortly after their only son had died. All of France was in mourning. She left 150,000 francs to Louis Pasteur, which enabled him to create The Pasteur Institute, and she left the store to its employees!

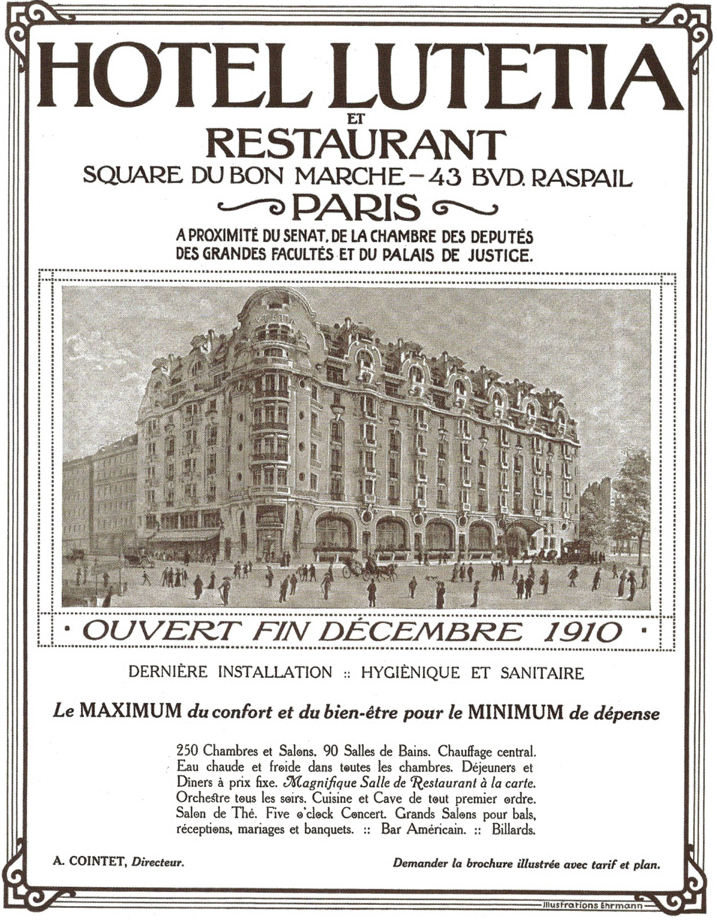

At the turn of the century, the owners of Le Bon Marché began to consider building a hotel opposite the world-famous store so that important customers could stay nearby in comfort, just as they had encouraged the building of the Gare d’Orsay nearby for the convenience of their customers arriving by train. (It is now the home of the Musée d’Orsay and its Impressionist collection.) In 1910, the Lutetia opened in the Art Nouveau style with designs by architects Louis-Charles Boileau and Henri Tauzin, and the interior by Jules Leleu.

During WW I the Lutetia was taken over by the American Red Cross and it functioned as a hospital. Throughout the 1920s and early ’30s the Lutetia was the meeting place for the artists and literati of Paris; Gertrude Stein and her circle met there regularly. From 1935-37, the Lutetia was the headquarters for anti-Nazi German exiles who met in the hotel to build a popular front against National Socialism. Among them was the author Heinrich Mann, who headed the group, which was known as Der Lutetia-Kreis (The Lutetia Circle).

World War II

From September 1939, when Germany invaded Poland, refugees fled to Paris from areas occupied by German forces. Because of its reputation, the Lutetia was filled with displaced artists and musicians. However, beginning June 2, 1940, when the Germans first bombed Paris, the city began to empty. On June 14th, Germans entered and occupied Paris and most of the French were evacuated. In 1944, when Paris was liberated, the hotel was taken over by French and American forces. From then until after the end of the war, it was used as a repatriation center for prisoners of war and returnees from the German concentration camps. (Of the 2.5 million people deported, mostly Jews, only 40,000 returned. Although Germany had demanded the deportation of all Jews 16 and older, the Vichy Government rounded up younger Jewish children as well and shipped them to Auschwitz.)

During the 20th century, ownership changed several times. In the late 1980s, the designer Sonia Rykiel supervised a major redesign of the interior of the hotel intended to recreate the Art Déco style of earlier decades.

The last time my wife and I stayed at the Lutetia was in January 2009. At that time the hotel hosted (and boasted) the small Paris Restaurant, which had one Michelin star, as well as a wonderful brasserie specializing in seafood. Le petit déjeuner, with the most wonderful croissants, brioches and other assorted breakfast treats, was served in the breakfast room–or en chambre. In April 2014, the Lutetia was closed for major renovations that involved gutting virtually the entire building. In addition, a swimming pool was added (required by the Paris government for the hotel to call itself a “Palace”). The hotel did not reopen until 2018. Prices on the hotel’s website for early May 2023 began at €1,480 (~$1,600) per night, and at €2,000- €3,000 at other times. Today, the hotel has five food venues. The brasserie remains, but the Paris and its star are gone. And for us, it’s a great place to visit, but we can’t afford to stay there. G&S

Note: For this article I have drawn on the book “Hôtel Lutetia Paris–100 Years,” ©2009 by Éditions Lattès, in cooperation with the hotel (which included the photo of DeGaulle), which was given to us as we were departing in 2009. Other photos by Norman A. Ross

Leave a Comment