People who know that I once wrote regularly for Rolling Stone for over a decade and spent a lot of time hanging out with rock stars, hardly believe me when I tell them that the period I remember most fondly, and would most like to be transported back to, if time travel were possible, was the mid-sixties, when I belonged to a community of obscure young artists showing their work in funky storefront galleries on East Tenth Street.

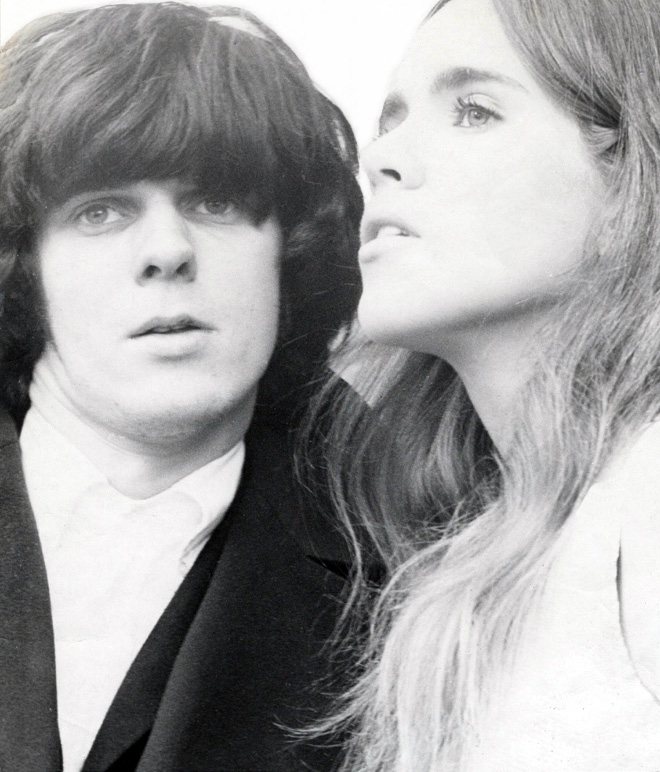

At that time, my new bride Jeannie and I had created our own little bohemian fantasy pad in my parents’ attic in working-class Staten Island. We would pore over books such as the profusely illustrated paperback, published in 1961, called The Artist’s World in Pictures by the Village Voice staff photographer Fred W. McDarrah. A year earlier, McDarrah had published another book called The Beat Scene, an anthology of poetry illustrated with his own pictures. (A slick operator, McDarrah had also cashed in on the Beat craze by starting a “Rent a Beatnik” service, supplying poets to enliven square suburban parties.) However, as we perused these books, it gave me a feeling of being on the outside, looking in.

Eventually however, with Jeannie continuing to work as a receptionist even during her pregnancy, our combined salaries meant that I could now afford the $15 monthly membership of an artist-run gallery.

Among the ten or more artist cooperatives that made up the Tenth Street scene, I chose the Brata, which was on Third Avenue, right around the corner from Tenth Street, because my earliest literary hero Jack Kerouac had once given a poetry reading there.

Jack was the first real Beat poet I ever met. I had known Jack since the late 1950s, when I dropped out of high school because I was bored with it and knew you didn’t need a diploma to beatnik anyway. I met Jack reciting his rhythmic hophead city poems in Washington Square Park. I already knew who he was. Kerouac had won a poetry competition at the Village Gate judged by Charles Mingus, jazz critic Nat Hentoff, and hipster radio monologuist Gene Shepherd.

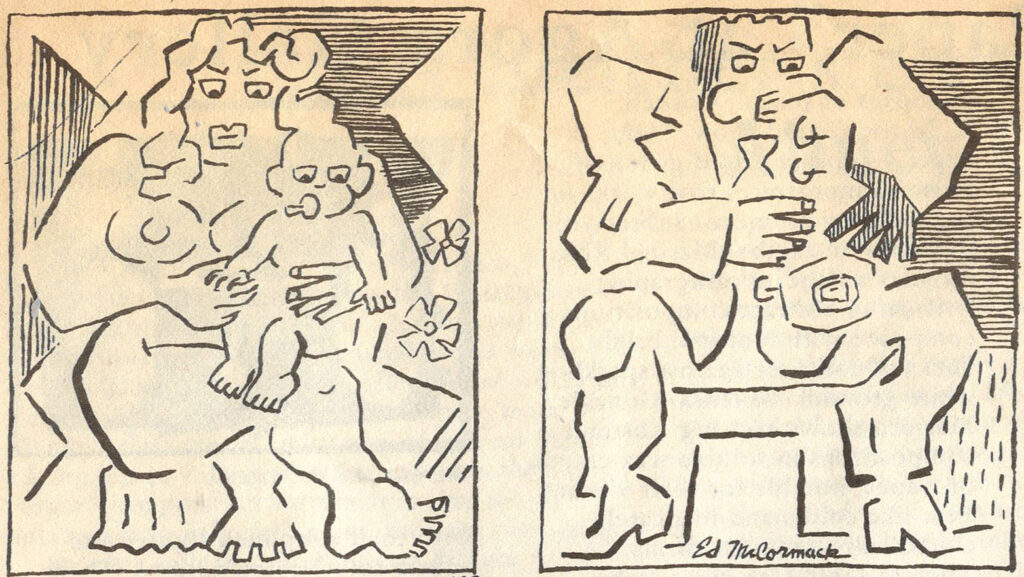

First however, I had to be voted in by the current members of the Brata Gallery. So, Jeannie and I both took off from our jobs one day and carried two of my paintings over to Manhattan for them to look at. Since the Abstract Expressionist aesthetic of Bigger Is Better still prevailed on 10th Street, we chose two six-foot-square canvases that I had painted, spread out on the attic floor. One was of a stylized jazz musician; the other was of a mother and child locked together like the pieces in a puzzle –– the latter probably inspired by my subconscious anxiety about becoming a father. We rolled them up and carried them across the bay on the ferry like rug merchants; Jeannie insisting on carrying one herself despite her pregnancy.

Waiting nervously in its dank cellar waiting for the members upstairs in the gallery looking at my paintings to arrive at a verdict, I called Jeannie’s attention to an army cot piled with notebooks and paperback books in the corner near the furnace. Since the books were all thin chapbooks that I recognized and a few articles of clothing, such as ancient suit-vests that were invariably wore over t-shirts or frayed, un-ironed dress shirts as sort of a sartorial trademark, I was sure they belonged to Jack Micheline, one of San Francisco Bay Area’s first Beat poets and painters.

I don’t think I ever felt as anxious about anything I had to do later as a feature writer for Rolling Stone, (the publication that according to the Columbia Journalism Review, “spoke to an entire generation,”) as I was that day waiting with Jeannie to see if I would be accepted as a member.

Thankfully we were thrilled to learn that I was voted into the Brata Gallery and told my paintings would be included in an upcoming group exhibition. We waited with great anticipation for the start of the show.

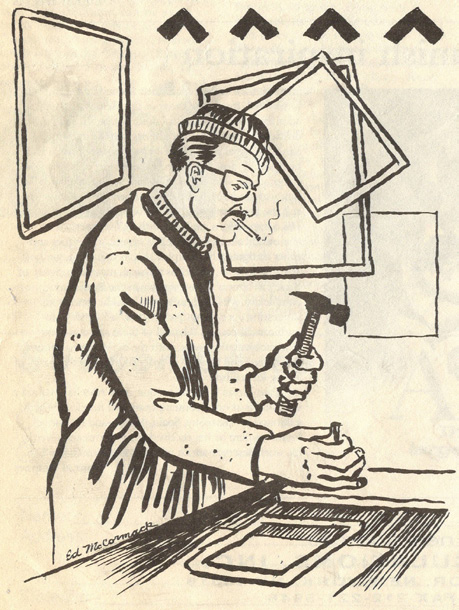

But, on the night of the opening, when we traveled in from Staten Island we went into a panic. It was just an hour or so before the reception started, the gallery was locked, and while we could see through the big plate glass windows that, while all the other paintings were already on the walls, my two big canvases were still unstretched and spread out in the middle of the floor. I had hired John Krushenick, who ran the frame shop in the back of the gallery, to mount them on stretchers for the show, but he was nowhere in sight.

John Krushenick had started the gallery several years earlier with his brother Nick, soon after they both got out of the service and decided to go to art school on the G.I. Bill of Rights. Nicholas, as he called himself professionally, had since become well-known as a hard-edge abstractionist and moved on to more posh uptown galleries, along with other former Brata members who had made good, such as Al Held, Ronald Bladen, David Seccombe and Yayoi Kusama. But John, who painted baseball game battle scenes and other oddball subjects in a less fashionable neo-primitive figurative style, was left behind to eke out a living in the frame shop. Painfully shy and polite when sober, he underwent a Dr. Jekyll-to-Mr. Hyde transformation into a wild man when he drank, challenging men to fist fights and chasing woman customers around the gallery like a satyr in one of those classical paintings he sometimes liked to crudely parody in his own primitive style.

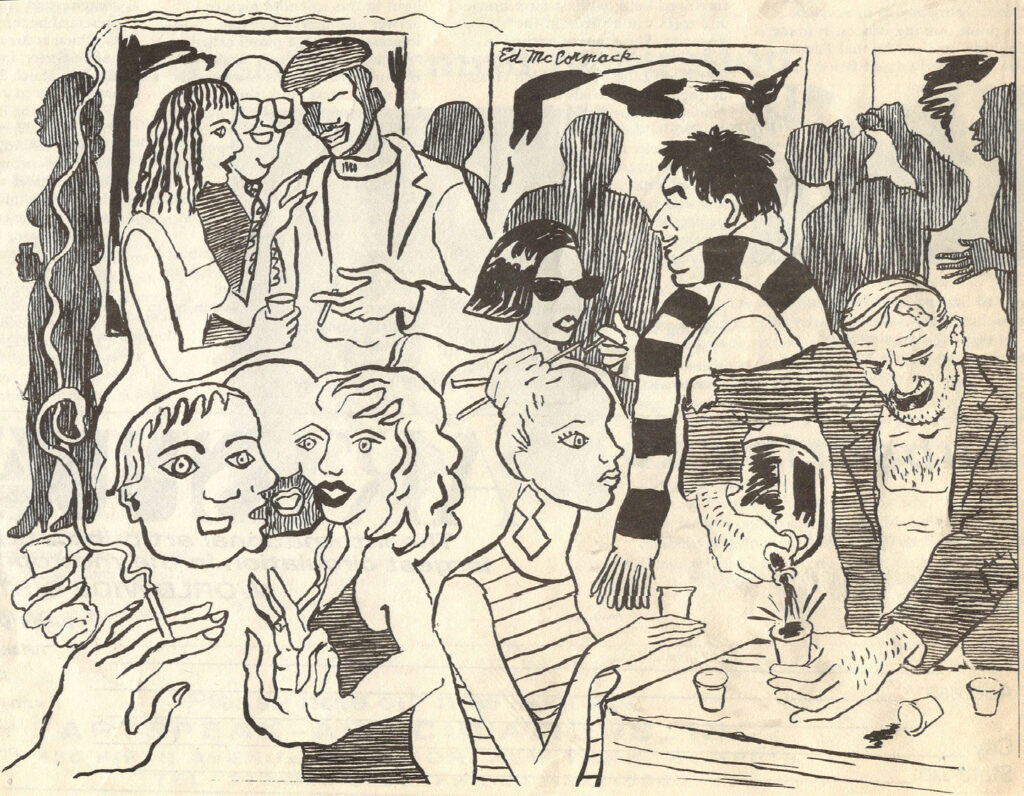

While Jeannie and I were standing on the sidewalk staring forlornly into the closed gallery, an artist who knew John came along, shook his head when we told him our problem, and mentioned a couple of places where John sometimes hung out. When we didn’t find him at the Cedar Tavern on University, we rushed over to a bar on Saint Mark’s Place called The Dom, downstairs in the same building as a former Polish meeting hall that had been painted Dayglo blue and turned into the Electric Circus, a trendy discotheque where Andy Warhol staged his first mixed media events, “The Exploding Plastic Inevitable,” starring The Velvet Underground.

“Tell her he isn’t here,” Kruchenick was yelling to the bartender, who had just told him his wife was on the phone as we rushed in the door. Taking his change off the bar and shoving it into his pockets, we pulled him off the stool and dragged him back to the Brata, where he banged two sets of stretchers together and managed to get my paintings up on the wall, however lopsidedly, with just minutes to spare before the opening reception was scheduled to begin.

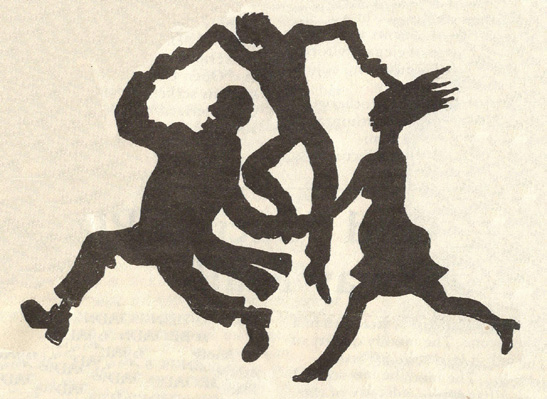

Then, with his knit seaman’s cap falling over his eyes, and a Marlboro burned down to the filter in his mouth, John Krushenick stretched out his arms to my pregnant wife and me, saying, “give me your hands,” and linked like the figures in Matisse’s famous painting, we danced triumphantly all around the gallery. G&S

Ed’s Grab Bag is a storage folder of his memoir notes and stories.

Leave a Comment