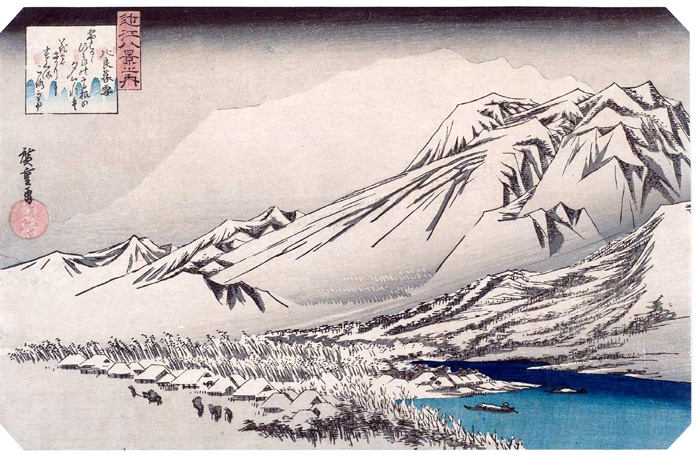

1833, color woodblock print on paper, 8 7:8 x 13 11:16 The Mary Andrews Ladd Collection

Oregon’s Portland Art Museum possesses one of the most comprehensive permanent collections of Asian Art on the West Coast, boasting many masterpieces. From December of 2022 through early May of 2023, the Museum has on display 67 of its greatest woodblock prints in a show called HUMAN/NATURE. These superb works represent a genre of Japanese art called Ukiyo-e that flourished from the 17th through the 19th centuries.

Twenty of the prints are the product of the fertile imagination of Utagawa Hiroshige. Born with the name Ando Tokutaro, the young man came into a family with a samurai lineage. After his parents died in 1809, he took up painting and by 14 began his studies with teachers at the Utagawa school in Edo, which was the main workshop of Ukiyo-e. While kabuki actors and women were often subjects, the masters and students at the school also created remarkable prints that introduced the deep perspectives found in Western landscape art. By the time he was 15 in 1812, his masters permitted the young man to sign his work with his art name Hiroshige, a tradition known as a go—something akin to a writer’s pen name or pseudonym. He also used the surname Utagawa after the founder of the school Utagawa Toyoharu (c. 1735 – 1814)

Hiroshige’s primary work was in the field of landscape art, and by the early 1830s he was starting to produce his greatest pieces, including multi-print collections like Eight Views of the Edo Environs and Fifty-three Stations of the Tokaido. Yet, despite the brilliance of his work, he never seemed to receive the lucrative commissions that some other artists did. In fact, before his first wife died in 1838, she often helped finance his trips to sketch outdoor locations by selling some of her clothing and ornamental combs. During the last decade of his life, he created thousands of prints to meet the demand for his work, yet never seemed to be financially comfortable.

In 1856, he decided to “retire from the world” and became a Buddhist monk. It was during this final period of his life that he created what many consider to

be his masterwork: One Hundred Famous Views of Edo. Sadly, this prolific artist—he left behind over 8000 prints—died in 1858 at the age of 62 as a probable victim of a cholera epidemic that was sweeping through the country.

color woodblock print on paper, 8 7:8 x 13 3:4 The Mary Andrews Ladd Collection

At least two of his students went on to have reasonably successful careers, and both had the distinction of being his sons-in-law. Hiroshige’s daughter Otatsu married the man who would assume the art name Hiroshige II. And after they divorced, she married Hiroshige III. Yet neither man achieved anything near the fame of their father-in-law teacher.

And that fame spread from East to West rapidly, especially influencing French Impressionists like Monet and artists like Cézanne and Whistler. Probably the greatest homage to Hiroshige came from Vincent Van Gogh who meticulously copied two of the One Hundred Famous Views of Edo that were among Vincent’s personal collection of Ukiyo-e prints.

One of the astonishing prints from his early career is Shono, Driving Rain. This 9″ x 14″ horizontal image—dating from 1833—is from his series Fifty-Three Stations of the Tokaido and is generally regarded among Hiroshige’s masterpieces. Here travelers and two porters carrying a client in a traveling chair are forced to run through a sudden and heavy rainstorm near the town of Shono in Ise Province. The thatched roofs of houses are visible on the right through the torrential diagonal rain. Further adding to the sense of drama are the dark rows of trees bent low by the wind across the background. Hiroshige is giving us an evocative, theatrical depiction of humanity’s vulnerability and stimulates our imagination so that we, too, can hear and feel the rain and wind on our own bodies.

From the same period is Twilight Snow at Mount Hira, part of the series titled Eight Views of Omi. It’s another brilliant print that reduces the mountain landscape to its severe bleakness with only a few minimal strokes without losing any depth perception. The blue bay (the only significant use of color in an otherwise black and grey world), the small village, and nearly Lilliputian travelers on the roadway at the very bottom are juxtaposed with the overwhelming mountaintops; this depiction helps to create a sense of the monumental, despite the image measuring only 9″ x 14″. The poem in the top left cartouche adds to the beauty. It has been translated by Matthi Forrer and Peter Mason in Hiroshige: Prints and Drawings (London, 1997):

When it clears after snow fall the tops of Mount Hira at dusk surely surpass the beauty of cherry trees in bloom

Keeping with the winter theme, we move forward nearly 25 years to 1857, and discover two prints from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo. The 15″ x 10″ vertical print called Atagoshita and Yabukoji Lane uses only three colors (a brilliant blue especially) that perfectly captures the stillness of a snowy scene. In the distance is the district known as Atagoshita, after its location “beneath Mount Atago,” the hill rising to the right. The towering bamboo grove—also shown on the right—was an established landmark recognizable to Edo residents. It lay just outside the northeast corner of the mansion owned by the powerful landowner in the feudal domain of Minakuchi and served to protect the site from the “dangerous” northeast, where the Kimon—the “devil’s gate”—lay. The bamboo gave its name to Yabu (“Thicket”) Lane, an alley that ran along the back of the wall of the mansion. Although mentioned in the title, Yabukoji Lane is out of sight in this view, behind to the right.

Even more dramatic is Fukagawa Susaki and Jumantsubo. Measuring 14″ x 9,” this vertical print presents a view that looks northwest from Fukagawa Susaki, a spit of land along Edo Bay, toward Jūmantsubo, a tract of land named after its approximate area of one hundred thousand tsubo (which is about eighty acres). Certainly it remains one of the most dramatic designs of the entire series. Its brilliance lies in the contrast between the powerful eagle as it prepares to dive for prey and the bleak wintry marshes below. Despite there being no people visible in the scene, there is still the sense of a human presence. There is, for example, a suggestion of rooftops to the left along with what appear to be poles in a lumber-yard beyond. Yet perhaps the most prominent “human touch,” is the lone wooden bucket floating at the edge of the bay, surrounded by water birds upon whom the eagle seems to have set its hungry eye.

So—for those unfamiliar with Hiroshige, do yourself a favor and explore his work online or—better yet—if you live in a town or city with a museum that has holdings of Asian Art like those in Philadelphia, Boston, New York, Houston, or Portland—to name just a few—be awed in person. Hiroshige never disappoints. G&S

Leave a Comment