Gift of Henry Failing Cabell

Since retiring from a full-time undergraduate professorship in the arts and humanities in 2011, I’ve become a museum docent, showing people through exhibits and, among other things, exchanging ideas about various pieces of art and cultural artifacts. I know from first-hand experience that it’s all too easy for any guide to slip into “teacher mode” and recite hopefully interesting historical tidbits such as: “This teakwood bow was made by a member of the Kono tribe of West Africa and dates from 800 CE.”

Lately, however, I’ve switched gears and am listening far more to visitor reactions to a particular work. Yes, I’ll fill in some blanks —names, dates, possible social significance— but now I spend a significant amount of time hearing what speaks to the guest.

Recently, I took a friend —Michael— to the Portland Art Museum and set him loose in two of the American wing galleries. I asked him the “desert island question”: If you could go home with only one work in this hall, which one would it be and why? Which work speaks to you?

After spending a solid hour of careful looking at a few dozen works in both galleries (which included his diligently reading the label copy next to each work), Michael had two “winners.”

The two pieces he chose were as different as different could be, but each “said something” to him. He began with a caveat, however. “If I really had my way, I’d probably prefer an outdoor sculpture garden rather than an enclosed gallery. I like three-dimensional pieces and enjoy being able to look at something from various angles and in various lighting conditions.” In other words, “I want to see the bird out of the cage.” I thought that was very interesting.

But he was more than willing to take up the indoor gallery challenge, and so he went through both rooms without any comments from me. I stood in a corner, avoiding any “hovering.” It was mindful looking on his part, and “shut off the professor” on mine.

In the Anne K. Millis Gallery —which is devoted primarily to 19th and early 20th century art— the clear winner for Michael was Alfred Bierstadt’s 51″ x 60¼” oil on canvas titled Mount Hood, painted in 1869. Bierstadt (1830-1902) —heavily inspired by the Hudson River School painters, especially Thomas Cole who also loved to paint scenes on a grand scale— became famous particularly for his landscapes of the American West. He composed these works in his New York and London studios from sketches, notes, and small oils that he made during his extensive travels. The resulting pieces —like Mount Hood— gave his primarily urban viewers a sense of place rather than a realistic record of a particular location.

Mount Hood, for example, seems to depict a view of the mountain from a single vantage point along the north shore of the Columbia River; in reality, the painting combines at least three different views. Yet this bending of reality was done for dramatic effect. And Michael certainly responded to “the effect.” After spending a good five minutes absorbing the scene, he waved me over to join him. He was particularly taken in by the foreground trees —“You can almost see individual leaves and branches.” He also noted the remarkable lighting on the mountain and the palpable morning haze. But what struck him most was the detailed presentation of the deer in the lower right corner: “I can really imagine being there with them.” Clearly, Michael was responding to the intentional monumentality and detail of the work rather than its potential lack of geographic accuracy.

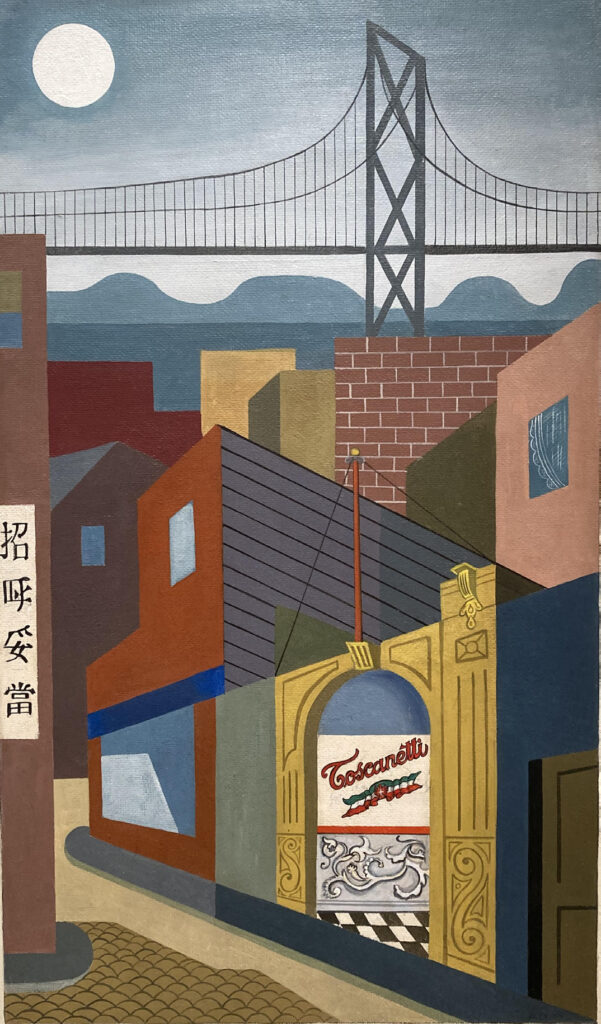

Michael’s choice in the Janet and Richard Geary Gallery was Hilaire Hiler’s 30″ x 20″ oil on Masonite scene called San Francisco Street. Painted in 1936, Hiler’s work is very different from the near photorealism of Bierstadt’s Mount Hood. This is a work that clearly complements some of the paintings by Hiler’s contemporaries, Joseph Stella and Charles Sheeler. It’s two-dimensional and linear, with every building stripped down to its geometric essentials. If Bierstadt’s painting throws the observer into the midst of nature, Hiler’s San Francisco Street places the viewer into the angular reality of an urban setting.

Hilaire Hiler —painter, costume and set designer, muralist, musician, writer, and psychologist— was born in St. Paul, Minnesota. As he grew, so did his wanderlust, and he ended up living in various places in both the United States (including San Francisco) and Paris, France (where he died in 1966). Throughout his career, Hiler gravitated more towards abstract imagery, and by the 1940s, his theories on color and abstraction developed into a movement which he termed “Structuralism.”

For Michael, San Francisco Street —especially the Oakland-San Francisco Bridge floating beneath the moon— was inviting. “I gravitate towards something I know or can picture in my mind. While I can certainly appreciate the effort, the form, the structure, or the colors of a completely abstract work, I want to enter into something more familiar and dialog with that.”

It turns out that Michael is an accountant; he lives in a world of mathematics. On the one hand, this painting’s precision was familiar territory; it pleased his order-seeking mind. On the other, just as the “reality” of the leaves, the lighting, and the deer in Mount Hood spoke to him, so did the bridge and the nearly baroque signage for Toscanetti’s restaurant on the lower right. He did notice the sign in Chinese on the far left border, but as the grandson of Sicilian immigrants, it was the sign for Toscanetti’s that resonated. He imagined “the food and baked goods” of his youth.

My trip to the Museum with Michael was engaging. He is open to all kinds of art, but he gravitates most towards things that create familiar resonances—such as the serenity of deer feeding on a misty morning or the comforts of

an Italian restaurant on a moonlit night. Yet what was most apparent about our visit was that by going to an Art Museum, he was being open to having a conversation —not only with the person he was with, but with the painting he was looking at, and listening to.

Some pieces will whisper, some shout, and some will remain silent. The trick is to accept that reality and not judge the reaction. So, Michael loves Bierstadt, and

I love Clyfford Still. Yet that difference can create a most wonderful conversation. G&S

Leave a Comment