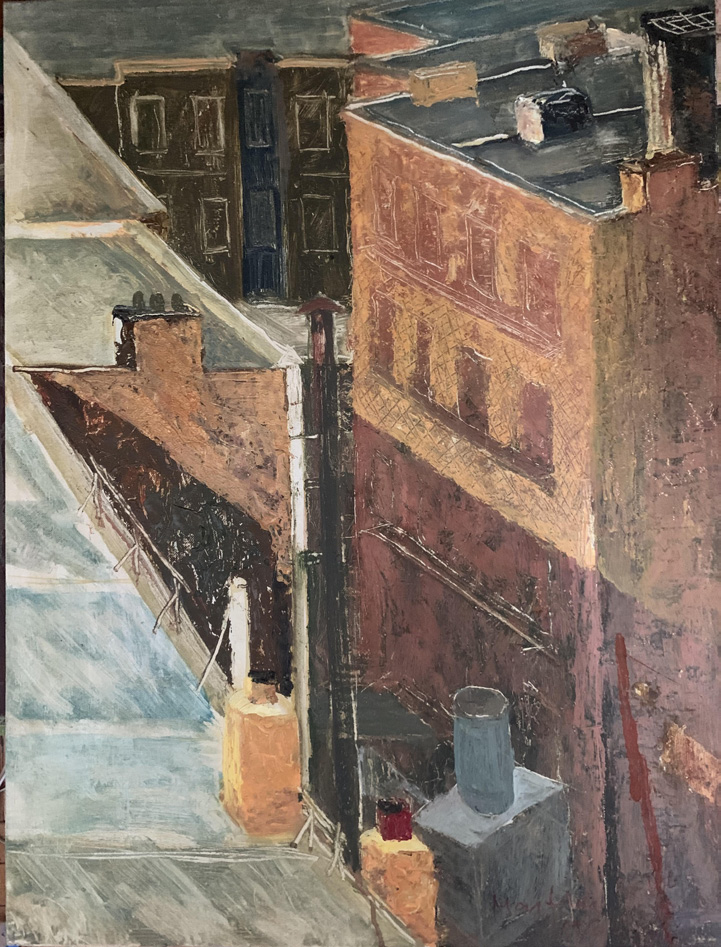

Shrouded with mystery, the cityscapes of Martha Szabo haunt rooftops and skylines —views she saw daily from her penthouse studio. Her stunning paintings range from an early focus on urban geometry to an emerging metaphysical take on that busy, yet unpopulated cloud arena wreathing the tips of skyscrapers. Rooftops, spires and cornices gracefully mutate in high-rise space, where Szabo peoples the usually barren urban scene with a cast of wraiths appearing as finials and shadows. And she contrasts New York’s fat-bellied water towers with the mundane, flat expanses that architects think no one will ever see. Spectacular scenes are nevertheless gritty as this behind-the-curtain view visits unpretentious apartment buildings, where once working class stiffs in T-shirts played pinochle, and immigrant women hung their laundry in competitively designed lines of blowing trousers and drawers.

The marvelous chemistry of city forms and Gothamite gumption emerges in the mixed and subtle light of many of these canvases. The shadow witnessing of the built environment reminds us that brick, mortar and stone are part of the city’s great circulatory system, carrying us from moment to moment, connecting people across neighborhoods and ethnicities.

The modest chimney pots in the foreground of Untitled (circa 1963) point the eye towards the subtle shade of building bricks caught in slanting light.

In Bridge after Sunset (1975), the parapet is crowded with figures silhouetted against a blush sky and the cloud-capped Queensboro Bridge. In both works, city geometry is animated, claiming space as a character.

Born in Debrecen, Szabo was schooled in modernist Budapest, scarred by World War II and revived as an immigrant in the late 1950s wave of Hungarian refugees escaping Soviet domination. Her professors leaned to modernism, and she forged her own style early on, painting mostly portraits and landscapes. At age 93, Szabo has seen much, painted much and is ripe for one of those stunning discovery moments when the world wakes up to the treasures they missed, as the museums bypassed such artists.

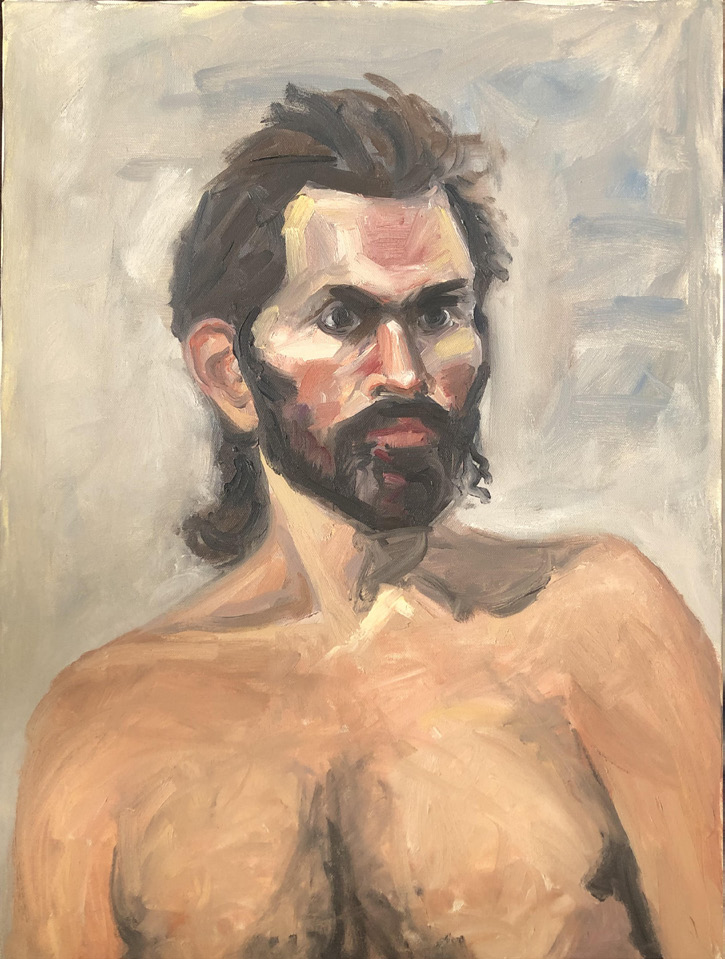

Szabo’s open mind is striking. She sees people as people, and captures who they are with respect and a voyeurism-free curiosity. This open-minded approach radiates from her many Art Students League portraits, where models appear in unusually casual poses as part of the panoply of possible human beings. Race, class, gender, are readable but not ideological, and categories dissolve in the humanity of her portraits. As someone who twice in her lifetime had her freedoms brutally smashed, Szabo’s ability to depict freedom with her brush is a tribute to the survival of the best of the soul through the worst of its trials. For example, a confident Latino nude meets our gaze with a glare, refuting any attempt to undervalue him as “just a model.” Szabo’s vision emphasizes how his gloriously tousled hair and powerful chest exude a confident sexuality.

Many portraits were rapidly executed, as she benefitted from painting live models at the Art Students League (ASL) of New York. Her mentor there was the instructor Hananiah Harari, a proponent of modernism who had studied with Fernand Léger. Although she was already a mature artist with her own style by the time she started frequenting art classes at ASL in the late 1980s/early 1990s, one can compare Szabo’s fluent, personalized portraits to Harari’s lyric expressionism. Interestingly, Harari was an artist who gracefully bridged styles and schools, painting in turn abstractions, expressionist work and realist precisionist pieces, as well as drawing illustrations and doing murals under Burgoyne Diller during the WPA years. Szabo painted directly in oils, which she would let dry in her locker at the League. ”I like to work with oil paint,” she says. “I can do the things I want to do with it… I can change it, make it finer or heavier.”

With paint applied in long assured strokes, Szabo captures the individual qualities of her models. An older lady in a jaunty felt hat flaunts nail polish that matches her red-lined purple coat, underscoring her confidence and urbanity, even as her sneakers indicate a preference for mobility over fashion.

Like many of Szabo’s portraits, this is compassionate, yet unflinching in detailing wrinkles and loose, crepey skin. Age is proud. Many of Szabo’s nudes have awkward folds, unflattering bulges and disproportionate limbs, yet all project self-assurance, a confidence that Szabo is glad to grant them. In the sprightly portrait of a nude woman reading, the painters applies witty red spots to toenail, nipple and cheek.

Skipping lightly over studio conventions, Szabo’s life paintings often encompass other painters, so that the figures seem to converse. For example, an artist in red shirt paints an oversized male model wedged in the foreground. His curvy buttocks and incipient man boobs lend his powerful figure a touch of androgyny. Another intriguing pairing depicts a slim nude woman, eyes lowered as bold slashes of white define her downward gaze, seated in front of a “twin” onlooker dressed in strappy black dress and glamorous hairstyle. Both women jut an elbow out, hand on hip, adding a note of defiance to their parallel pose. These might be the same woman, pre- or post- modeling session.

Every encounter with powerful art reconfigures the viewer’s sensory operations. Expectations eagerly seize upon what the eye perceives, filing it in our mental cubbyholes. Indeed, the work’s credibility may rely on its escaping viewer assumptions. Szabo’s art gives us an opportunity to rethink how we define figurative art, especially in regard to portraits.

While, yes, we can read personality and character, we are literally seeing splashes and daubs of oil paint whose colors form edges and guide the eye. And this is one reason I was delighted to realize there was no useful distinction between Szabo’s people and pet portraits. Different species of New Yorker, her dogs and cats are imbued with attitude like her life drawing models —and are just as abstract.

Torkan the cat is as jaunty as the Musketeer D’Artagnan, her plump body gathered into a fat ball with tiny paws and dapper whiskers. Torkan’s eyes are high beams glaring from their perch in a furry black tonal experiment. Szabo’s nine lives have spanned many chapters of high modernism, while escaping easy categorization. Her legacy rewards our open minds. G&S

Leave a Comment