Until the late 18th century, youngsters reading on their own or being read to encountered much sermonizing and few if any engaging pictures. Gradually, society recognized that children deserved playful and gentle guidance. Imaginative stories, amusing poems, and captivating illustrations began to eclipse moral lessons.

In the mid-1860s, Edward Lear’s A Book of Nonsense featured outlandish animals and people in silly situations with whimsical limericks, and John Tenniel’s fantastical drawings enhanced Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Mary Mapes Dodge, founding editor of the children’s magazine St. Nicholas in 1878, declared her goal as “clean, genuine fun” that instilled “a love of country, home, nature, truth, beauty, and sincerity.” Such fare would also encourage “good, pleasant, helpful ways.” Palmer Cox’s Brownies and Rose O’Neill’s Kewpies crystallized this blend of joyfulness and selflessness in charming imaginary beings and rhymes about their escapades.

Born in 1840 in Granby, Québec, 22-year-old Palmer Cox moved to San Francisco and —with a minimum of art training— wrote articles and drew newspaper cartoons until he moved to New York City, where his Brownies debuted in St. Nicholas in 1883. His drawings in the Ladies’ Home Journal and similar magazines soon won adult affection for the Brownies. Over the next 35 years, Cox published 16 Brownie books and numerous magazine pieces and comic strips. He directed two Brownie musical plays and the sheet music for Effie F. Kamman’s Ragtime piano piece The Dance of the Brownies sold a half-million copies.

Cox derived the elfin characters from his Scottish grandmother’s folktales. In Scotland, the Brownie is an invisible solitary male with weathered brown skin who performs household tasks during the night. Shaggy and dressed in rags, he is generally benevolent but may become malicious if not left bits of food for his labors. Cox’s Brownies, however, are a fun-loving, sociable troop of “little sprites who…delight in harmless pranks and helpful deeds (and who) work and sport while weary households sleep and never allow themselves to be seen by mortal eyes.”

With rotund figures, spindly legs, goggle eyes, and long pointed shoes, they are nonetheless irrepressibly agile. They have personalities, occupations, and nationalities indicated by the prevailing ethnic stereotypes of the period. Cox excluded Africans and African-Americans, an omission typical of publications aimed at White audiences. His lilting iambic tetrameters recount their exploits.

In The Brownies Abroad (1899), they romp through several countries and explore architecture, history, geography, and nature. They gamely rescue each other from mishaps like a pratfall into a volcanic crater. In the Brownies at Waterloo, they visit the Lion’s Mound, a Belgian site of the 1815 British and Prussian victory over Napoleon. An English Brownie, identified by the tattersall suit associated with British gentleman, confronts a disgruntled French Brownie wearing a Napoleonic bicorne hat as if celebrating the British triumph.

A Dutch Brownie in wooden clogs watches his companions scale the monument. The Brownies wander around the battlefield, discuss military strategy, and try on army gear at the local museum. Such tales gave children a vicarious experience of self-reliant, adult-free adventures. While it is easy to dismiss Cox’s verses as juvenile doggerel, he does not spare young readers from the violence of war:

“’T was here Napoleon sat like stone,” Said one, “unmoved by shriek or groan…And saw his squadron sink from sight, Still rank on rank in ghastly plight, When like a living stream they flowed, To burial in the sunken road.”

In about 1904, Cox built the 17-room Brownie Castle in Granby that later became his retirement home. A Brownie flag flew from its turret until his death in 1924. In Cox’s obituary, The (New York) Sun noted that the artist’s 70th birthday celebration had brought “gales of merriment” to all in attendance.

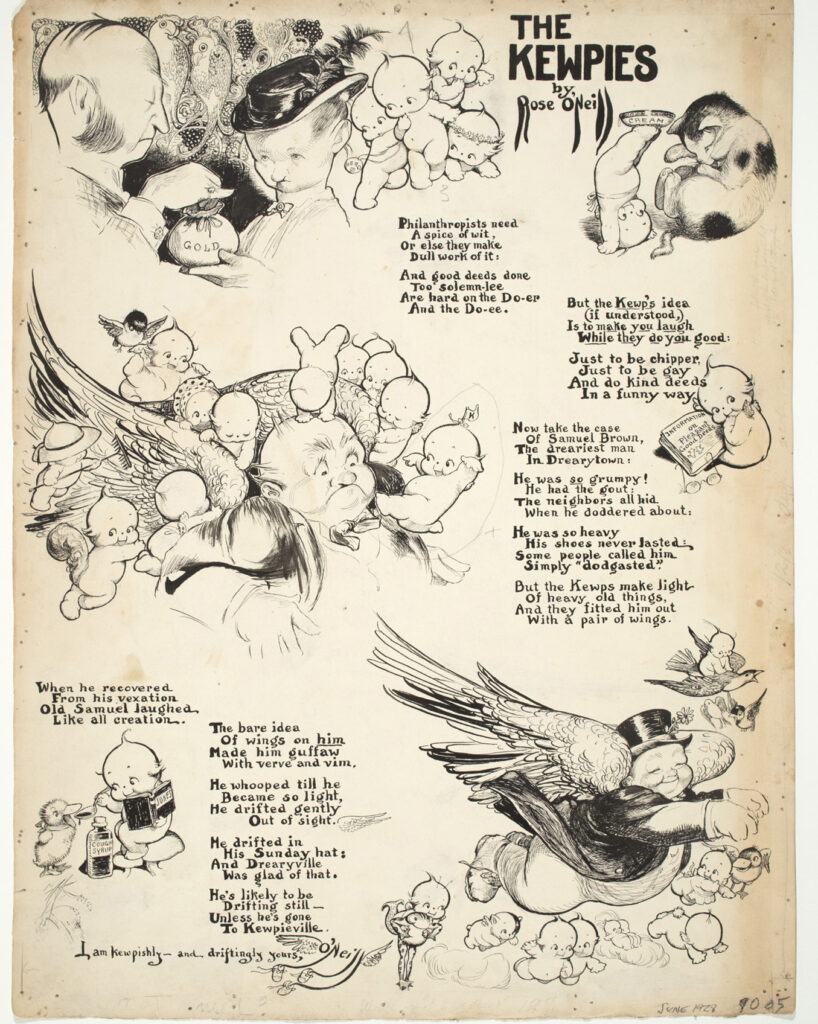

More whimsical characters were introduced by Rose O’Neill when her Kewpies came to the Ladies’ Home Journal in 1909. She described them as “a sort of little round fairy whose one idea is to teach people to be merry and kind at the same time.” They evolved from Cupid-like figures that O’Neill used to decorate her romantic fiction. She spelled their baby-talk name with a K “because it seemed funnier.” Floating or earthbound, Kewpies “do good deeds in a funny way.” They were white top-knotted boys with tiny wings, though O’Neill renders them angelically sexless.

Cox’s Brownies may express displeasure, but gleeful Kewpie sidelong glances invite us into never-ending revelry. O’Neill’s poems accompanied each drawing. Over time, she gave the Kewpies names, costumes, and occupations. O’Neill recognized her debt to Cox in a 1914 drawing of a Kewpie looking shyly at a Brownie with the inscription:

“The Brownie was reverently copied from my dear old Brownie Book of 1887. (Apologies to Mr. Cox). A Kewpie meeting a Brownie, I’m sure, would be almost overcome with respect.”

(1874–1944) Ink on paper sheet: 22½ × 17¼ inches Delaware Art Museum, Gift of the Rose O’Neill Foundation, 2018. © Estate of the artist

The public embraced the Kewpies, and The Washington Times noted that “Not since the days of the Palmer Cox Brownies has there been an army as popular.”

When O’Neill was 13, she won a drawing contest sponsored by her hometown newspaper, the Omaha World-Herald. Self-taught, she soon sold illustrations to other publications, and by 1893 moved to New York City, where in 1896 she became the first American woman to publish a comic strip. She joined the staff of Puck, the nation’s premier humor magazine, where she was the only woman working from 1897 to 1903. Initially in black and white and then in color, Kewpies appeared in magazines such as Life, Harper’s Bazaar, Cosmopolitan, and Good Housekeeping, as well as books and comics, for the next three decades.

In O’Neill’s Kewpie page for the June 1928 Delineator, the Kewpies’ humor and magic transform a begrudging philanthropist into a beguiled, airborne one. They enliven their good deeds by entertaining a cat and tending to a sick duckling. Even O’Neill’s distinctive, long-tailed signature takes on wings.

O’Neill’s accomplishments surpassed her moniker “the Kewpie Lady.” She wrote and illustrated magazine fiction and novels, including The Loves of Edwy, and several children’s books. Critics praised her exhibitions of graphic art and sculpture in Paris and New York. An indefatigable supporter of women’s rights, especially suffrage, she designed posters and political cartoons for the cause. In rejection of women’s prescribed clothing, especially corsets, she dressed in voluminous caftans. She divorced two husbands who abused her income and good nature.

O’Neill’s generosity to friends and family helped deplete the fortune earned during her career. In 1937, she left New York and returned to Bonniebrook, the home she had purchased or her family in the Ozarks, where she died in 1944.

The Brownies and the Kewpies were irresistible to advertisers and merchandisers. Before the 1891 U. S. Copyright law passed, artists had little control over the use of their images. Cox was one of the first to exercise his copyright. He profited from the Brownies’ adaptation in a range of products, including games, toys, and dolls.

Although Eastman Kodak violated his rights by appropriating his imagery to promote the Brownie camera, companies such as Procter & Gamble hired him to illustrate their ads, capitalizing on the Brownies’ aura of sincerity and optimism. O’Neill followed his example to even greater effect. Beginning in 1912, she oversaw the production of Kewpie dolls, which quickly became an international craze.

Spin-offs includeda wide array of Kewpie merchandise, from housewares to greeting cards to car-hood ornaments. Kewpies frolicked through ads for Jell-O and Kellogg’s Corn Flakes.

Today the Brownies still delight collectors, and the International Rose O’Neill Club Foundation will again gather in Branson, Missouri, for their annual Kewpiesta convention. G&S

© Mary F. Holahan, 2022

Leave a Comment