I want to transport all of you—no matter where you live or how far you are from Wilmington, Delaware—to the Delaware Art Museum to gaze in wonderment at Howard Pyle’s paintings. I have a problem, though. My magic wand is at the shop for repairs, and the only way I can do this will be…Motivation.

I have to convince you that, as a reward for every valiant deed you have ever done, you must visit this incredible museum and drink deeply of its art.

Why?

I’ll start by telling you briefly about the Golden Age of Illustration, an era recent enough that your grandparents’ bookshelves will have been filled with copies of books given to them by their parents, and illustrated by Golden Age artists.

Cast your minds back to those aged volumes: Gold embossed covers. Frayed cloth bindings. Deliciously thick ivory pages. And evocative front pieces, often covered with tissue-like paper that seems to proclaim, “This is Art. Handle with Care”.

Many books on those old, old bookshelves—such as Robinson Crusoe, Arabian Nights, and Treasure Island – were illustrated by N. C. Wyeth, Maxfield Parish, or Frank Schoonover. They, and dozens of artists like them, were students of Howard Pyle.

Even Norman Rockwell, just 17 years old when Pyle died, credits him as a source of inspiration. In a 1962 Esquire magazine interview, Rockwell was asked what artwork he would take to a desert island, and instantly replied, a “Rembrandt or two” and “a good Howard Pyle.”

So why do we remember Wyeth, Parish, Schoonover, and Rockwell, but we have forgotten Howard Pyle?

Generational stupidity? Cultural malaise? Mass hypnosis? I haven’t a clue.

The antidote, however, is at the Delaware Art Museum, where Howard Pyle’s paintings are on the walls, majestic, inspiring, and at long last, on permanent exhibition.

Let me tell you a little about Pyle.

First of all, he wasn’t your stereotypical angst-ridden artist. He loved what he did, and he did it brilliantly. He adored his wife, and had seven children on whom he doted. He kept regular hours, never charged his students for their lessons, and was as generous with his wisdom as he was with his advice, to wit: “A subject… should hold some great truth of nature or humanity, so that a person seeing it would give a part of his life’s earnings to possess so beautiful a thing”.

Pyle considered himself to be an artist first and illustrator second. Over much too short a lifetime – he was only 58 when he died – he produced more than three thousand illustrations and wrote (and illustrated) over twenty books.

He was passionate about his work. “If you are going to be an artist, all hell can’t stop you. If not, all Heaven can’t help you”.

When Howard Pyle painted a battle, it realistically portrayed the slump of a shoulder, the grimace of pain, the flutter of a scarf, and the pathetic vulnerability of a soldier’s bare feet as he laid dead in the dust.

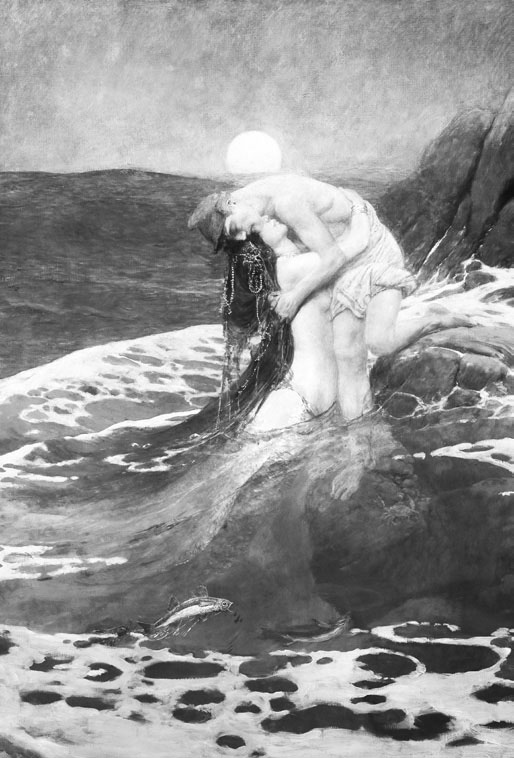

“The Mermaid” – 1910, Howard PYle (1853-1911) OIl on canvas, 57 7/8 x 40 1/8 in, Delaware Art Misei,. Gift of the children of Howard Pyle in memory of their mother Anne Poole PYe, 1940

When Pyle illustrated gladiators fighting to the death, we see the tense muscularity of naked flesh, and we feel the savagery of an upraised arm about to thrust a knife into an opponent’s heart. We smell sweat, we hear the roar of the crowd, and we see cruel streaks of sunlight cutting through the arena like the slashes of a blade.

His mermaids entice, allure, seduce, and captivate.

And his pirates!

Before Howard Pyle painted them, they looked, in reference books, more like prosperous merchants than lawless buccaneers. Pyle imbued them with style, romance, menace, and flair. He put gold loops in their ears and swords between their teeth. He made them fiercely virile, with cruel glints in their eyes, tattered clothes on their bodies, and adventure in their hearts.

“I have always had a strong liking for pirates and for highwaymen, for gunpowder smoke and for good hard blows”, Pyle stated.

The look he created for pirates has extended, virtually unchanged, from the first one he painted to those portrayed in silent movies, in MGM musicals, in Walt Disney’s Peter Pan, and even to our current love affair with The Pirates of the Caribbean, of which four sequels already have been made… With more to come.

Watch those movies.

Visit the Delaware Art Museum and study Howard Pyle’s pirates. After that, look at his Revolutionary War soldiers. His Golden Galleons. His gladiators. His Medieval Knights. His scoundrels. His lovers. And his mermaids. Then, appropriate to the 4th of July, stand in awe before his pensive and beautiful portrait of Thomas Jefferson signing the Declaration of Independence.

While you’re at it, pick up a couple Pyle books: For a start, Pirates, Patriots, and Princesses and Robin Hood. Read them to your children. Honest to goodness pirates, outlaws, and archers are a thousand times more thrilling than any computer game.

Better yet, bring your children, your grandchildren, your parents, your sweethearts, and your friends to the Delaware Art Museum, and personally introduce them to Howard Pyle.

Why?

Because the soul needs sustenance.

Because it is important that we integrate beautiful things into our lives.

And because Howard Pyle has produced magnificent works of art.

Leave a Comment