Wally Gilbert is renowned in the artistic world for bold and blazing works of digital art, most recently on exhibit at Chelsea’s Viridian Gallery. The apt title for this exhibition was “Transformations.” Gilbert, who first enjoyed great success as a scientist doing pioneering work in molecular biology, made a huge career switch. He left the rigors of laboratory research and decamped to the studio to pursue new work that broke established boundaries and satisfied his intellectual curiosity.

Now his scientific background subtly and powerfully informs his artistic expression. In 1980, Gilbert won many scientific awards and honors, most notably for the 1980 Nobel Prize in Chemistry which was shared with Frederick Sanger and Paul Berg. They were honored for their pioneering work in devising methods for determining the sequence of nucleotides in nucleic acid.

When asked about his “transformation,” Gilbert says he became intrigued with photography as an art form around 2000. “I discovered that I could make

large pictures using a 2 megapixel camera—everyone said that this could not be done. But I added pixels and found that the eye completed the image.” With this revelation, Gilbert decided this was an art form he wanted to pursue. The new focus on digital art was, as the writer Marcel Proust once observed, a real voyage of discovery, not seeking new landscapes, but having new eyes.

As he gained expertise, Gilbert used natural images—photographing ballet dancers, a decayed factory in Poland, and geometric patterns with small digital cameras. Today he only uses his iPhone but is still interested in isolated fragments.

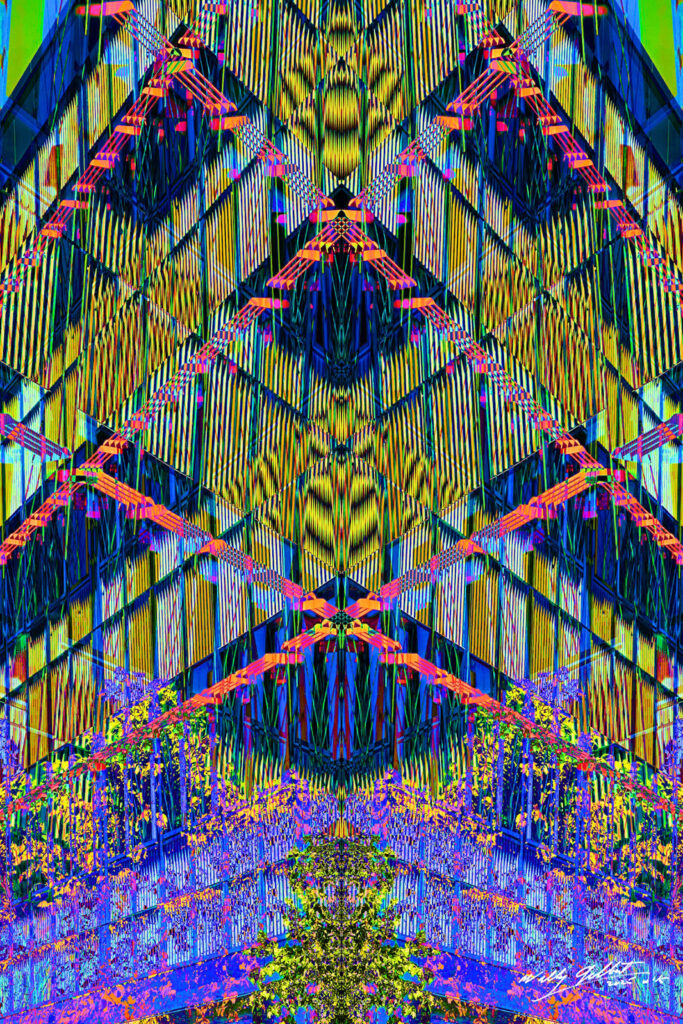

Describing his technique, Gilbert says he usually frames the picture with the camera. “I overlap similar or different images in the computer using Photoshop.

I generally drive all the colors to 100% saturation.”

This requires the technical precision of a scientist who understands form and structure.

“I have the layers interact by processes that create differences, or multiply or divide the pixel colors on the layers. Then I play with the overall color tones on each layer,” he says.

Usually, Gilbert makes 36″ x 24″ images which he prints on aluminum, a commercial process that first involves printing on paper, pressing the paper against the metal, then using heat to move the dyes. “I can go up 72″ by 48″ with this technique,” he says. All of the work in the Viridian exhibition was printed on aluminum.

Color is central to Gilbert’s work. As he says, “I am delighted by strong colors, vibrant colors which can be transformed and deepen the strength of the image.”

Among the many exuberant works of art in the Viridian exhibition was Red and Blue Leaves, a picture of a plant where the colors are taken to 100% saturation.

“The overall hues are changed until I find a pattern that I like,” Gilbert says. It is just one example that reveals his background as a scientist. He seems to approach each artwork as an experiment, testing ideas and exploring outcomes which imbues his pieces with a sense of inquiry and discovery.

Three Differences started as a picture of the sky above a building behind his house in Cambridge. “I made larger and larger versions of that image and overlapped three of them, taking differences between the image layers—hence the name of the work. When the colors were taken to saturation, the new interactions became other pictures in the show.”

Walter Gilbert’s journey from scientist to artist is a testament to the enduring power of curiosity and creativity. As he says: “My search is for a three-dimensional effect on a two-dimensional surface. I search for depth beyond the picture plane and for mystery.” G&S

Leave a Comment