Unless you’ve been living under a rock, you’ve probably had your fill of media hype surrounding artificial intelligence and how it’s either going to transform society into a utopian paradise or be the trigger for some apocalyptic doomsday, complete with hordes of killer robots roaming the streets. While either extreme is unlikely, I can tell you that as of now, it may have already claimed its first victim.

“Photographic evidence” used to be a term to describe an unimpeachable depiction of something that really happened. When you needed to convey the notion that an event was real, a photograph was supposed to be an unblinking narrative of the truth. That started to fade as technology progressed. Stalin was notorious for keeping a staff of retouchers on speed dial, ready to erase comrades that had fallen into disfavor. Long before anyone ever had a thought of deleting their ex from a selfie, disgraced officials were shot or sent to a gulag and deftly removed from any publicly accessible photos.

But back then, when photography relied on film and chemicals, retouching was a difficult process that needed time and considerable skill to do convincingly. As technology evolved and cameras went digital, so did the retouching tools. I can recall a field trip to a print shop back in the 80s where they had what looked like a sci-fi version of a computer lab, replete with men in white lab coats and state-of-the-art workstations whose processing power would now be dwarfed by the iPhone that sits in your back pocket. When Photoshop came along, it introduced a set of tools that would allow the kinds of image manipulation that Stalin could only have dreamed of.

As remarkable as all that was, digital retouching was still based on the old model. An image. A person with a creative vision. A set of tools. All working together to alter or create a depiction of reality. What AI brings to the table is an entirely new paradigm. With AI, the “person” making the changes has been replaced by a set of chips and wires residing in a datacenter. You don’t use tools to make changes, you literally tell the AI what you want it to do and like some futuristic jack in the box, it proceeds to shuffle zeros and ones to produce the desired result.

What’s really remarkable is just how good the results can be. In fact, the easiest way of detecting an AI image is by how overtly perfect they are. As of now, its rendering of reality can sometimes miss the nuances of an uncombed head or the random scattering of acne that reality calls for.

I’m not even going to try to explain how it works…I actually don’t think I could if I tried. Rather this is a first person account of what I’m observing as a photographer with roots in tradition and now as a witness to the most profound change imaginable.

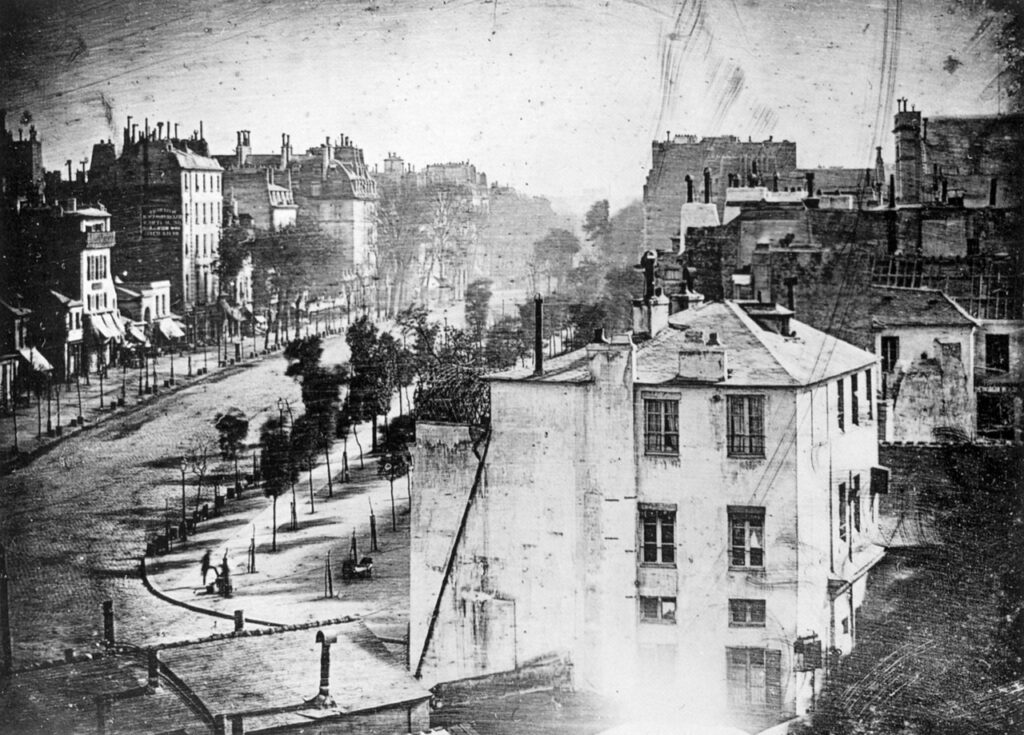

Let me start at the beginning. This is very first known photograph to contain a human being… Louis Daguerre’s Boulevard du Temple taken in Paris in 1838. At first glance, the street looks empty, but that’s only because the long exposure (several minutes) made moving traffic and pedestrians blur out of existence. The only reason we can see people at all is that one man on the lower left, having his boots shined on the sidewalk, remained still long enough to be captured. Everyone else on the bustling Parisian boulevard simply disappeared due to movement during the exposure.

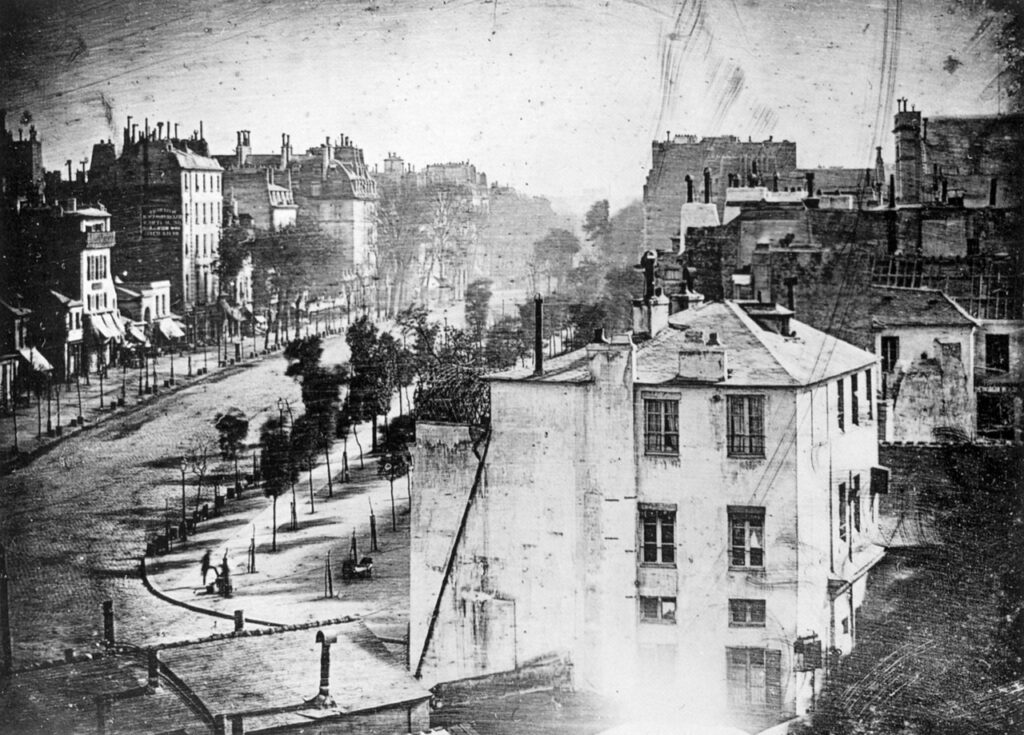

Here’s the same image, uploaded to an AI engine with intentionally vague, instructions to “clean it up.” In my imagination I could almost hear gears grinding and flashes of lightning bolts arcing up through some scary looking hardware but in reality, it was just my usual cursor spinning for about a minute as the AI did its thing. I didn’t tell it to make it look painterly. I think it picked up its cues that it was a very old photo and tailored its rendering to suit. I could just as easily have added a parameter to make it look like a modern photograph or for that matter, do it in the style of Edward Hopper or Roy Lichtenstein and the results would have faithfully skewed towards whatever I told it to do.

Also consider the amount of thought that went into the rendering. The shadows are consistent, the perspective is accurate, visibility fades in the distance as the haze intensifies, and the surfaces of the buildings are worn and textured, as you’d expect in an old neighborhood. To me, that’s the most remarkable aspect—the presence of an entire world’s worth of context without explicitly stating it. In this brave new era, we don’t use tools to create and manipulate images; instead, we collaborate with an AI model and communicate our desired outcomes.

“Photographic evidence” used to be a term to describe an unimpeachable depiction of something that really happened.

The implications are remarkable. Imagine a world where the camera, photographer, subject, lights and setting are all replaced with an imaging engine that can be endlessly manipulated for free or a minuscule fraction of what it would have cost to do it in real time. The unemployment line for commercial and portrait photographers starts here.

I can recall a time when ad agencies had teams of illustrators and retouchers on staff, ready to render whatever concepts that their creative teams could come up with. At some point, there might be a hand-off to a photographer with years of experience, assisted by stylists, make-up artists, location scouts, models, even catering companies and set builders all in service to realizing that idea. In the new workflow, all those roles are gone, every bit as redundant as buggy whip manufacturers were a century ago.

A moderately savvy creative can now prompt an AI engine to create an image out of thin air, or for a product shot, upload a reference image (nothing fancy, an iPhone photo will do just fine) and refine the lighting, perspective, texture, and composition to precisely fit their requirements. The notion that anyone can create a professional-looking image, simply by talking to a computer and telling it what to do, is something I still struggle to come to terms with.

It’s also worth noting that for all the remarkable capabilities, the current level of tech is still at its most basic and primitive. As computer speed continues to increase (doubling every 18 months!), that exponential rate of growth will lead to things we can scarcely imagine. In a real sense, photography as we’ve known it may actually be dead, replaced by something that I can’t begin to name.

G&S

Leave a Comment