Renée Borkow’s exhibition “Kaleidoscope” at Viridian Gallery from November 4-22, captures the wonderfully evocative spirit of its title. As a “viewer of beautiful forms,” she has created mixed media collages that take us along the High Line, New York City’s 1.45-mile elevated linear park and greenway built on an obsolete freight railway.

Completed in 2014, the park runs on Manhattan’s West Side from Gansevoort Street to 34th Street. The aerial landscape incorporates parts of the original tracks; some of the older tracks are still visible below at street level. As we share her vantage point on the walkway, Borkow transforms an array of human-made and natural sights into vivid montages of colors and forms. Geometric structures harmonize with organic shapes. Designs range from symmetrical to intricately varied. As she leads our eyes around her compositions, converging spatial dimensions and shifting proportions offer up-close and far-distant vistas. Familiar scenes become new, landscapes and cityscapes seem to change before our eyes. We are delighted by what the inventor of the kaleidoscope called “an infinity of patterns.” Words—descriptive, witty, or cautionary—enhance the images’ moods.

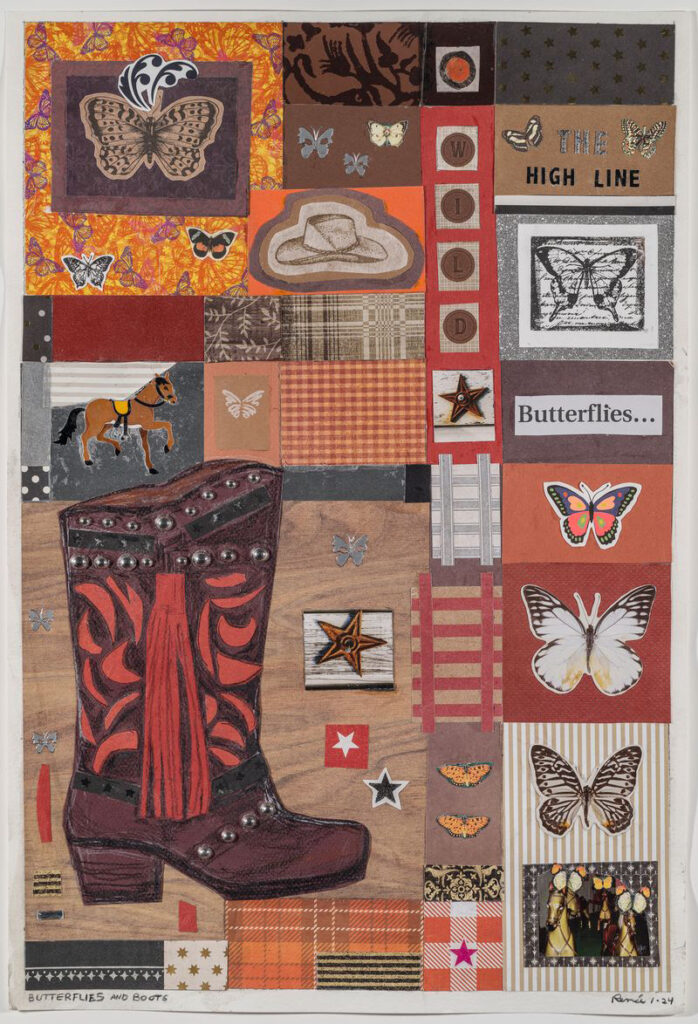

Borkow’s collages interweave allusions to history and ecology. In Butterflies and Boots, a cowboy boot accompanied by sheriffs’ badges and a Stetson hat may seem out of place in a New York City landmark, but the work celebrates the “West Side Cowboys.” These men were mandated by a mid-19th century law to precede the then-street-level trains, traveling at no more than 6 miles an hour, “on horseback, to give the necessary warning in a suitable manner on their approach.” Perhaps the decorative boot commemorates the last rider, George Hayde, his boot tassels swinging as Cyclone, his yellow-saddled horse, steps along the path.

On our airborne stroll, flat red and gray ladder-like forms become train tracks and intersecting streets. Their right angles and grids evoke the hard edges of the city’s architecture and industry. But colorful irregular squares and rectangles also summon up the softness of a home-made quilt. Such an abundance of colors and patterns suggests the High Line’s billboards and murals, and even glimpses of our fellow-walkers’ clothing.

Borkow gives her butterflies a spectrum of hues, markings, and personalities. One in Butterflies and Boots appears in black and white with transparent wings over calligraphic script, a reminder of early botanical specimen drawings. A second sports an ornate, feathery headdress. Others in defiance of urban captivity triumphantly fly off into a radiant field of orange-yellow. Breaking away from the collage’s subdued palette, their soaring flight and prismatic colors remind us to notice and embrace the High Line’s uncultivated wildness.

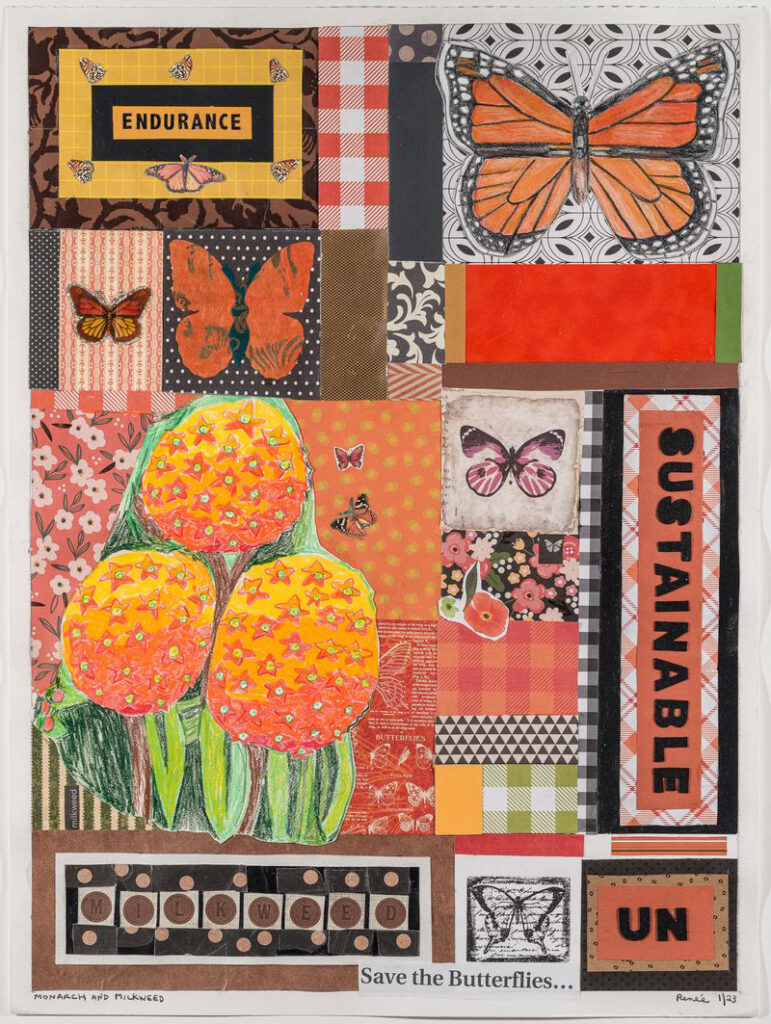

Butterflies are often the stars of Borkow’s High Line works. They seem to surround us as they hover and alight. Monarchs and Milkweed highlights the dramatic orange wings (often with a 4-inch span), black veins and borders, and bright white-dotted edges of the Monarchs. The word ENDURANCE respects their long-distance seasonal migration and survival despite climate changes and loss of habitat. The word SUSTAINABLE and its negative UN are notes of hope and warning. Borkow’s stylized milkweed flowers and greenery have pride of place: High Line horticulturalists have planted varieties of milkweed, the Monarch caterpillars’ sole host plant and an important food source for adults, to help ensure their survival and the local biodiversity.

Also included in Monarchs and Milkweed is a detailed artistic rendering of a text and butterfly design for the study of butterflies. Similar to the black and white counterpart in Butterflies and Boots, the image reflects our long-standing attraction to the enchanting creatures who symbolized the soul to the ancient Greeks. Borkow’s sensitivity to the allure and resilience of butterflies recalls the ground-breaking work of botanist, entomologist, and artist Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717), a founder of lepidoptery. Merian’s exquisite illustrations of butterflies aspired to compelling exactitude, and Borkow’s collages reveal their wondrous and emotive beauty, but the scientist and the artist share a respectful fascination with these fragile beings.

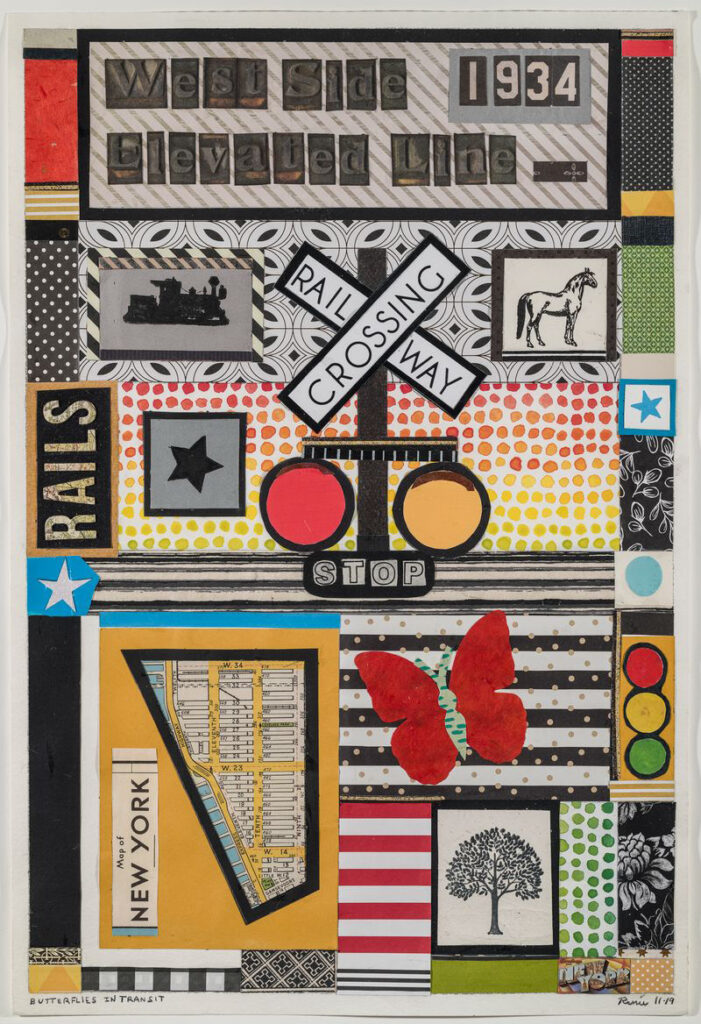

The weathered metallic sign for the West Side Elevated Train at the top of Butterflies in Transit brings to mind the line’s old tracks, completed in 1934. And in the map-insert, we see that those tracks ended at 34th street then, as the High Line does now. A horse, free of a saddle, no longer needs to announce the steam locomotive’s approach. Past and present mingle in other ways, too. Although trains have ceased to chug and clang, their insistent alarm bells are still part of city life. Then, as now, red, yellow, and green signals and railroad crossing signs govern our traffic on road and rail. And butterflies fly past STOP signs, while we stand still. Stately trees and swirling leaves catch our eyes, and bursts of brilliant color galvanize our spirit as we rush or saunter along the High Line and navigate the city. Butterflies in Transit echoes with memories, even while its line-and-dot patterns vibrate with our own daily rhythms.

The brief turn of a kaleidoscope changes fragments of different colors and shapes into a wholly new pattern. Endless turns will never yield duplicate views. Natural variability produces close approximations, but never exact repetition. Borkow’s collages attune us to the lively and always-changing world around us, and thanks to her eye and hand, we can all become “viewers of beautiful forms.” G&S

Mary F. Holahan © 2025

Leave a Comment