The word artist conjures a free spirit, one blissfully liberated from conformist pressures. And yet, often important artists are made—and their best work achieved—when they overcome restrictions. Case in point: painter Chunbum Park, for whom imagination is a lifeline, sacrifice is a vital part of the creative process, and limitations are lifted like kettlebells: burdens whose weight makes one stronger.

Born male in 1991 to a conservative South Korean family—the name Chunbum literally means “good at obeying the law”—Park identifies as female and currently lives with their mother, who prefers that her child abstain from cross-dressing. The artist chooses to yield to familial pressure, deferring their long-held dream of transitioning to womanhood. This selfless acceptance of limitation extends to their artistic medium: “I used to work in oil paint, but my mother has asthma, so now I work in acrylic.” Pausing the vacuum cleaner while assisting their mother with homekeeping, Park adds, with rare filial devotion: “She takes care of me now; later, I will take care of her.”

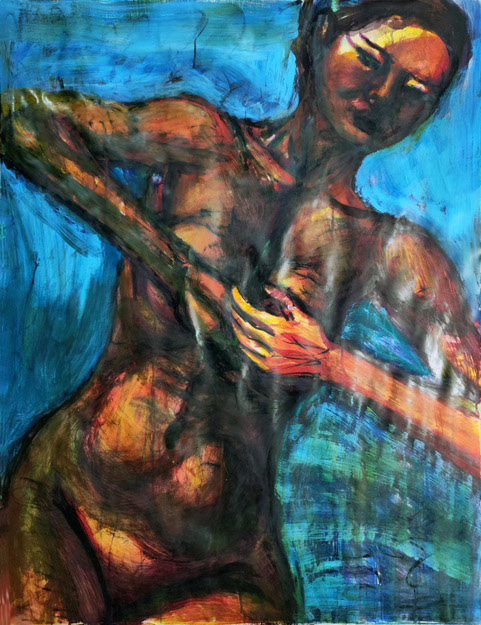

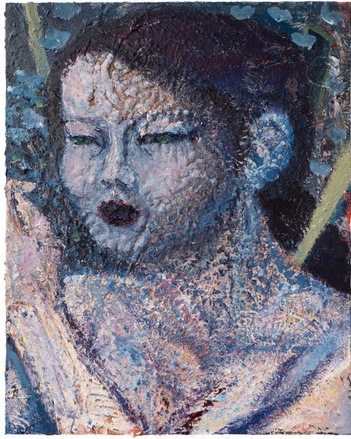

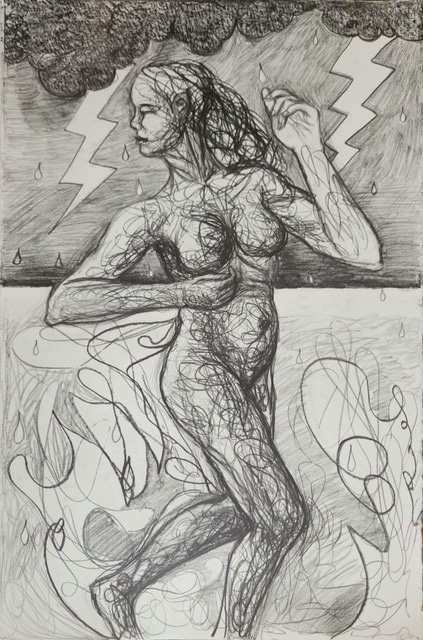

Art always transforms both artist and viewer; for Park, applying brush to canvas becomes an exceptionally powerful transformative process: painting the gender transition. “Through painting, I explore my own feminine energy, my desires, and the beauty of the feminine,” the artist explains. “In my paintings, I am a happy, healthy, beautiful, energetic, intelligent, sexy and powerful woman.”

Like a cosmetic surgeon, Park studies their own nude image and boldly remodels it. The physique is never quite “perfect”: part Renoir, part Gauguin, and part Jenny Saville, with a strong dose of lush painterly abstraction. Deploying their paintbrush like a scalpel, spackling on paint as if it were theatrical makeup, Park locates and relocates physical features, figuring and reconfiguring muscle and tissue, flesh and bone, as if fantasizing about the surgical process of transition. We see and feel the longing to soften angular masculine features, to anchor curvaceous female breasts convincingly on a six-foot-three male frame, to accent girlish extremities: fingers, hands, toes, feet—in Martha Graham’s words, the “miracle of the small beautiful bones and their delicate strength.” In Park’s operating theater, perfection is an attainable goal: Chun’s Secret Angel pays tribute to the winged supermodels of the Victoria’s Secret fashion brand.

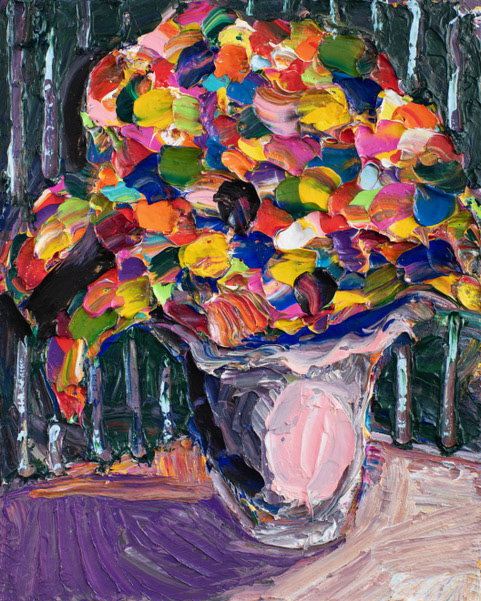

The evolving body is not Park’s sole subject; flowers are also a favorite. Capturing flowers has herstorically been a forte of the female artist. Perhaps more than their evolving self-portraits, Park’s flower paintings prove that the longed-for transition is as good as real; that the artist’s sheer imaginative force conquers any inconvenient physical fact.

Park’s flower paintings display a confident handling of color, with a pure, straight-from-the-tube palette: no whitened tints or blackened shades, just strong, naked, undiluted hues of red, blue, yellow, and so forth. Extra-virgin still life paintings by a bona fide virgo intacta, they are chromatic studies of virginity itself, the goal being “to explore hidden sexuality and eroticism from the perspective of a virgin.”

This is where Park breaks new art historic ground: traditionally, treatments of virginity in art center on the one “alone of all her sex”—the Virgin Mary. It takes considerable courage to be the virgin, to own and worry aloud about one’s own sexual experience, or lack thereof. Park addresses this most private topic in public as part of their artist statement: “How do I truly know who I am and what I want to become, if I am a virgin and have never had the chance to fully articulate my sexuality by actualizing it in physical reality? I fear with sadness that I will remain a virgin forever.”

Have no fear, Chun! Savor your innocence, however long it lasts. To quote your Ukrainian artist friend Rimma Simonova, whose encouragement inspired the title of a signature Park nude: “Chun, Keep Painting And You Will Win.” G&S

Leave a Comment