As Ansel (Adams) used to say, there’s an external and an that yeah, El Capitan is there and that’s the external event but the way you photograph it and how you see it, that’s the internal event and it’s the same way with people…you try and get them to where they look like folks.” I had the privilege of speaking with Charlie Tompkins this week and got to share some of the details of his life, photographic career, and unique processes that make him stand out.

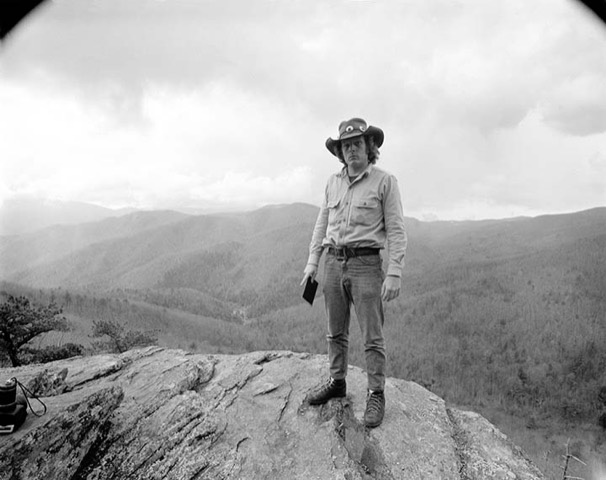

Born in Chicago, raised in Virginia, he is one of the lucky few blessed with both a vision and a lifelong drive to capture elements of his world as he experienced them. His website is replete with images that reflect his interactions with country, folk, and bluegrass musicians. Landscapes from Virginia to Alaska. Iconic portraits of musicians and contemporaries. Even the odd ghost town or two.

Growing up on a farm in Virginia didn’t strike me as an environment particularly conducive to an aspiring photographer. He had a lucky break when at a very young age someone gifted him a Brownie Hawkeye camera and he was curious enough to master its intricacies long enough to acquire a more versatile 35 mm.

“…my father was a businessman. His attitude was you’ll never make any money with that, even as a kid. I thought, ‘Well, that wasn’t really the objective.’ I think that even at that young age, I had an artistic temperament. I have done some business in the meantime, but I was kind of artistically inclined early on.”

As you’ll quickly notice, Charlie’s images celebrate film. For much of his career, his gear of choice was an old-style view camera with large format 4″ x 5″ negatives. This was once state of the art, mid-twentieth century technology, but unlike your iPhone, taking photographs this way requires focus, intentionality and the kinds of skills that come with time, experience and hard lessons learned.

This is work. You focus on a ground glass on the back of the camera where, due to the physics of a camera lens, the image is upside down and backwards. When you’re ready to shoot, a film holder replaces the focusing glass so that you’re actually blind at the moment you click the shutter. And it’s heavy. Add in a tripod, film holders, camera, and lenses, and you need a strong back and a skill set that can sublimate the equipment to the point where you can actually focus on the interactions with your subject.

“Photographically, I’m a strong proponent of “Silver” Imagery. A handmade silver print is a thing of great beauty, and it is like a little window of time. When we look into that window, we can see what a small slice of the photographer’s “reality” looked like at a given instant, frozen in metallic silver.”

The payoff is that the photographs reflect details of a scene with a kind of sharpness and fidelity that digital processes often miss. It takes so long to take a single image that you’re forced to pay attention to the details in ways that modern cameras with their digital enhancements are hard-pressed to allow. That lines up with his own observation of how his sharp vision was a key element in the evolution of his style.

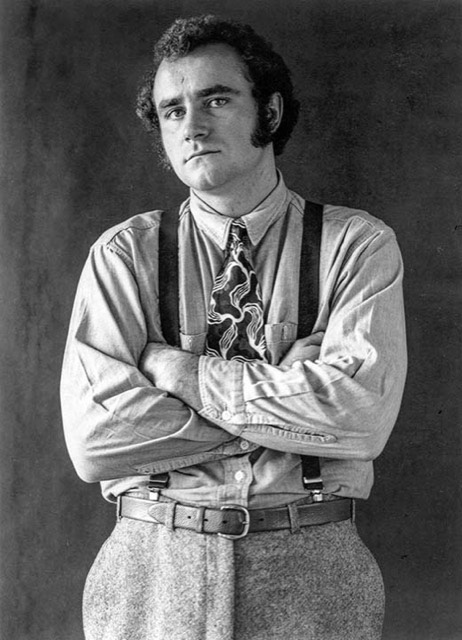

“I didn’t realize it at the time, but I had really good eyesight, and you know I sort of assimilated things through my eyes, more than verbiage. I could look at a person’s face and sort of make a discernment, whether they were telling the truth or what you know whether it was bored or whatever.”

He credits a series of workshops with Ansel Adams beginning in the late sixties for helping to define his vision. Uninspired by the commercial work he was doing in D.C., the classes provided the refinements he needed to regain his sense of inspiration. Adams was famous for his immense attention to detail. Charlie reflected, “…by the end of the workshop I was just struck by the craftsmanship that they practiced out there at that time.”

That newly acquired insight led to a focus on landscapes and collaborations with some of the leading folk and blue grass musicians of the era. Doc Watson, Allison Krause, Country Gentlemen, Howlin’ Wolf and Emmylou Harris among many others.

“I have done some journalism type things, but I really gravitated towards nature… and the musician, the concert thing is just because I have been a musician and so, I started documenting what I was going to see at the time”.

His sense of affection and comfortable familiarity with the subjects of his portraits shines through as much as his unique way of capturing them.

At 82, Charlie has a body of work extending over the last 70 years to reflect on. As the world changed, he was there to faithfully preserve its details for generations who may never know the love and attention that goes with clicking a shutter. I did get to ask him what’s next for him and he did concede that with so large an archive, digital has its place in preserving and restoring some of his work.

“At this point I am sort of going through boxes and boxes of negatives and film that I’ve already shot because so much of it’s never been seen. A few years ago, I was out in Skyline Drive, which is not far from here and I was trying to get a picture. I saw it there and I couldn’t get it right, it really frustrated me, and I finally realized that the reason I couldn’t identify with it was because hey, I’ve got one like this somewhere.”

Finally, in his own words….

“Life is like a mountain railway, with an engineer so brave, we must make each run successful, from the cradle to the grave.’ These words from a favorite country hymn say a lot about the way the world appears to me, that is, something of a journey. Photography is, to me, a means of recording, using one’s eyes, some of one’s pilgrimage.” G&S

Leave a Comment