With the use of the computer and myriad other electronic devices, some of the art created today seems removed from the immediacy of the expression of emotion. Many pieces do not “shred the heart,” to provide release of feeling. The true significance of art, its ability to move the spirit to give life meaning and integrity, is subsumed in quick bytes of imagery, without providing the viewer the opportunity to incorporate the imagery within and understand the message of the work on a very deep level.

Kathryn Hart’s visceral and profoundly moving work, like Robert Motherwell’s Spanish Elegies or Eva Hesse’s sculptures, creates pieces, weightily accessing the essence of experience and exploring feelings about life and death. Hart is a survivor, tenacious, intimately passionate while analytical, and a champion of life who names emotions, identifying what it means to live. Her recent exhibit, “Searching,” at The School of Visual Arts, demonstrates the range of her talents in sculptures, photos and drawings, a personal seeking for truth and identity where she is compelled to give existence import. She views life as a series of choices, made consciously and unconsciously, but not burdensome, which become a liberating expression of elemental forces.

Upon entering the exhibit, the first piece in the group was a site-specific diptych installation entitled, “The Search.” Hart therein deals with a constricted space creatively by expanding line and form within limitations, intricately incorporating tensile copper wire, fish line, thread, glass, ampoules, and washers with magnets that anchor the constructions in space. Line is very important to Hart and “The Search” reflects this by a plethora of various kinds of wires and strings, intricately knotted at junctures, with ampoules attached at different points throughout, refracting light and making the work shimmer and cast shadows in the space behind it. The sculptor’s act of knotting to create hubs for the lines to connect, forces her to consciously choose which subjects to address compositionally, allowing the lines to intuitively guide her towards the piece’s full realization. While creating the piece, she asks herself which direction she should take to go forward with the lines and extends this question to search for her path in life, working through any emotional dualities.

Hart refuses to be distracted by lush color, dealing instead in dark and light so that the viewer’s attention is not diverted by felicitous responses to hue. Instead, her use of white, black and grays brings gravitas to the subject matter, color only playing a part subliminally. The sculptor lives in the western part of the United States and unearths the ancient bones of animals found on her property there. She comes from a family whose life work revolves around the medical arts and she is not squeamish dealing with organic remains. She incorporates stripped down bones in the pieces she finds on forays into the forest around her home—her way of honoring the lives of animals and immortalizing them long after they have died.

In the photographic part of the exhibit, Hart creates a sensuous documentation of the bones in high key where these symbols of death are turned into undulating, beautiful abstract forms, and I am pictorially reminded of the ethereality of watercolor washes. The bones are randomly placed by Hart to be shot as one-time occurrences, and are just as ephemeral with regard to their longevity as the site-specific exhibit. The photos allow the remains’ transcendence so that they change into spiritual entities beyond death.

Hart also shows eight drawings, two per page, in ink on paper, both spontaneous and almost automatic. Her love of line resonates in these pieces where the markings are calligraphic and lyrical; as always, the line is her signature as the pen is uninterruptedly applied to the paper making one continuous psychic statement and continuing the flow of line found in the exhibit’s installation. Throughout the creative act, Hart wonders where she is going and what will be the destination in the work’s realization. She only understands the pieces’ underlying emotional impact for herself after it is finished and through her almost alchemical transformation of material, communicating this effect to anyone who views it. We react to the tensions of the lines, the somber tones, and we too feel Hart’s need to find meaning, transferring this emotion to our own lives. We are not perfunctorily surfing the internet, quickly moving between images; instead, like the artist, we experience our feelings, and when we see the work, our act of looking gains significance.

As Hart is very aware of her feelings, she titles her pieces carefully to support their deep emotional content. This can be found in her mixed media, “Dinner with Lazarus.” A few years ago, Hart almost died after enduring life-threatening illness. Part of the working through of this experience was her creation of this piece where the sculptor was able to confront her own personal vulnerability asking herself what it would be like to be Lazarus. Just as Hart survived near death, Lazarus actually experienced death and was brought back to life. Steel, leather and found objects in the work become a portal for Hart’s accounting of primal emotions at this experience, and the use of curvilinear wires, thick and jumbled throughout, underscore the fact that life happens to us as an untidy heap of events and is not organized in any way except through the meanings we give it. Hart could not control her becoming sick and she recognizes this fact in this piece, where any hints of color are almost consumed in the monochromatic thick gray overlays – but not quite, so subtle chromatic hints become the sculptor’s testament to her feelings that there is hope for the future and she is grateful to be alive.

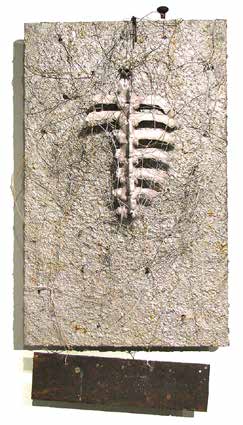

Another piece in the show, “Beast of Burden,” like “Dinner with Lazarus,” has minuscule shimmering spots of color under heavy gray and white layers, with hues subtly bubbling to the surface when seen up close. Parts of the spine and rib cage of an oxen’s skeleton are placed on top of these layers and Hart infers this might have been the remains of an animal leading settlers west in a covered wagon. The sculptor finds this piece symbolic of women who do the bulk of life’s work without being recognized, just as the animal sacrificed itself, in moving people across a harsh land. As in Eva Hesse’s pieces, the components are stark and unvarnished with Hart sharing some of the feeling of this German artist’s work.

Hart found it challenging to integrate the parts of the animal’s skeleton into the piece so, again, her use of lines in convoluted sinuous steel wires provide cohesion. A rusted horseshoe at the top along with an old steel plate hanging below the piece’s bottom edge, break up the strict verticals of the composition, both metallic elements being necessary for the work to be complete.

Robert Motherwell honored the suffering of the Spanish people in his elegies. There is no hope for the future to be found in those paintings. In contrast, Kathryn Hart, though her work is stark and somber in its examination of human existence, bringing us a chance for continuation. Both artists honor their subjects, but unlike Motherwell, Hart sees transcendence in death’s truth so that hope becomes the final certainty. Unlike in much of art today, Hart wrestles with what it means to be alive. Death is front and center but Hart is stubborn and knows that demise will not provide the last chapter; the yearning for life will remain no matter what the circumstances. For Hart, like Motherwell and Hesse, living is more than just quick moments in time, passing without importance. There is no mechanical interface between these artists and the viewers to dull the impact of the image; reactions are immediate as the work testifies to survival on so many levels and speaks directly to us opening our hearts to true meaning.

“Searching” seen recently at the School of Visual Arts galleries at 209 East 23rd St. and 380 2nd Ave.