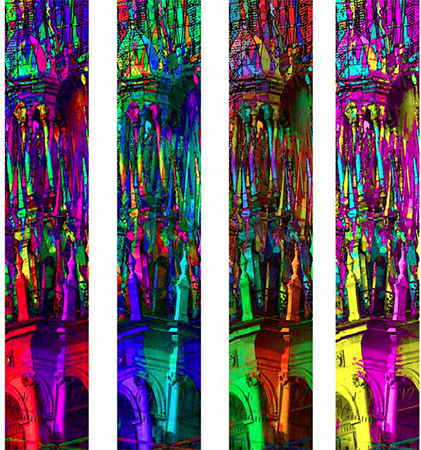

Something interesting happened when I went to see Wally Gilbert’s recent show, “Towers”, at Viridian Artists in New York City. I walked in, looked around, stopped and said “Whoa.” I love it when that happens. After a number of recent exhibitions of smaller works in group shows, seeing Gilbert’s grand symphony of colors and patterns on the walls caused a startling change in the atmosphere of the space, and in my imagination.

On the walls were large pictures, long and narrow, with bright colors and graphic patterns, in groupings of similar and often identical images. Photo based, but abstracted far from conventional photography, overlaid with vast changes of colors, ultimately creating profound shifts in the original photo image. But this show was not about photo imagery. I was stopped and confronted by the saturation of colors and the boldness of the patterns Gilbert was presenting. He was taking us away from photography on to other destinations. I’m fortunate to have met Gilbert before, and I know Viridian Artists since back to it’s 57th Street days. Gilbert has shown with them many times before, but I’m pleased to report on the outstanding advancement that he has made since his last show there three years ago. His explorations of color and pattern have taken a great leap forward. Gilbert has left behind any tentative introductions, and has jumped straight ahead to the drama that his colors and patterns produce together; drama not in any artificial sense, but rather in the immediacy and intensity of daily existence. I will explain shortly.

After a long and ultra-distinguished career as a molecular biologist (Harvard professorship, Nobel Prize, etc, etc.) Gilbert turned to the visual arts. Since then, he has continually explored and developed his image-making techniques. He first exhibited more-or-less conventional black and white photography, digitally recorded, but he didn’t continue with conventional photography for long. Unlike photographers who choose to create ‘documents’ using a camera that records a literal scene, Gilbert uses his camera like a butterfly net to collect patterns and shapes as a starting point. The images he chooses to begin with are rich in pattern and texture. Often he uses reflections and architectural elements of buildings, after which he chooses smaller portions of these patterns, and crops them, here into long and narrow rectangles. Using digital techniques, colors are then introduced. This is where the images begin to take on a new life. His previous exhibition introduced these colored patterns singly, but now he boldly presents us with multiple versions, using vastly different color palettes in each displaying them all together, like multiple strips of brightly dyed fabric. I could not help but be struck by the color, vitality and action in these works, which seemed to take me far away from the gallery in New York, to places in other parts of the world, where vivid colors and huge patterns in fabric and clothing are normal and expected. The cool grays and blacks and mildly colored accents that one sees in the big cities of the modern Western industrial world are replaced. Within seconds of walking in the door, I was transported to places far away from the West Side of Manhattan. I was carried to bustling marketplaces in countries where the presence of strong color and pattern is a daily, if not momentary occurrence; where fabric is sold in rolls or shards in marketplaces crowded with shoppers who will use them to create skirts, saris or headscarves. I looked around the room waiting for music or traffic sounds to fill the silence, waiting for the sounds of other languages, the movements of crowds, children and animals, behind and all around me, as they would in one of those marketplaces. Of course none of this occurred on West 28th Street, in New York City, except in my own mind.

What was happening here? After reviewing his exhibition in solitude and confronting my reactions to what I saw, I felt I needed to ask Gilbert about his intentions. How did he get to this place of color and pattern, one that created an essence this strong? Upon first viewing I couldn’t explain. I was simply enjoying the presence of these sensuous specters circulating around the gallery. It was when the immediate and exciting sense of adventure had calmed itself, that I became curious about how he managed to lead me to the places I found myself imagining upon entering the gallery. I know that he has traveled extensively, but has he, in fact, been to many of these places that have the marketplaces and fabrics which he evokes in this work? Gilbert himself is a vital and sophisticated presence, but his overt cultural references seem somehow delicate and tentative. He is reluctant to give explanations or talk about conceptual matters such as influences, and not given to abstract analysis of his artwork. “That’s your job,” he said to me, with a wry smile and perhaps the hint of a wink. So I changed my line of inquiry to areas I felt he would be more comfortable going into. I questioned him about his techniques, and he seemed far more comfortable discussing the various image-manipulating processes that led him onward to create the pictures on the walls in front of us. No mention of anything evocative of other times or places. But lest you think my imagination is running away with me when I extrapolate from Gilbert’s images on the wall to the vibrant fabrics found in marketplaces, he has, in fact, already experimented with this. When I entered the gallery, I had no immediate recollection of the several small scarfs on the shelf behind the desk at the gallery, gorgeously printed on silk, in a very limited run made during an earlier phase of his pattern explorations. About these, he was charming and modest in his replies, but he never quite answered my question about what inspired him to make this run of scarves, saying that this was an experiment, that the scarves were very expensive when produced in small quantities, and that he himself had no desire to create any more beyond these few, in terms of greater numbers or as an item for sale. But nevertheless, he did make this vital step, and I cannot imagine that it was a random experiment.

Notice I’ve used the words ‘explorations’ and ‘experiments’ numerous times. Let’s analyze. It seems quite clear that Gilbert is creatively restless, constantly exploring. His image making has advanced in clear steps with every new exhibition. Each of his exhibitions has been a point on an advancing line, where movement is the key. His explorations are diligent, like the experiments of the scientist that he is. He is very much the diligent scientist of his own artwork, and each advancement is comprehensible and satisfying. There is something reassuring about witnessing this continual progression, which has almost become a theme of his work, and a fundamental characteristic of both the work and the artist. While it may not necessarily be apparent from viewing a single catalog or exhibition of his, when one partakes of his body of work over the last ten years, it is readily apparent, and marvelous to behold. The line of progress that Gilbert is traversing is not merely an indicator of movement, but instead is a vector, indicating not just motion, but motion and velocity in a certain direction. Gilbert may be restless, but he is quite thorough in his explorations. He seems utterly unrestrained in his visual curiosity, perhaps dissatisfied with making halting steps, but confident that none of these explorations, regardless of the outcome, will take him anywhere that will slow this process. This confidence is quite contagious, I daresay; it is inspirational. I liken him to the captain of a ship setting off across unknown seas during the Age of Enlightenment. He seems like a captain who would inspire his crew in the face of adversity when entering unknown waters or landing on unexplored shores. No doubt this has been characteristic of his scientific career as well. His results speak for themselves.

How does an artist get to this place? How does he get there throughout a career as a chemist and scientist working with modern technology in the big modern world of New York? When embarking on such a journey, does an artist simply travel along with the counterclockwise rotation of the planet, arriving in tropical oceans and islands in due course? No, there is still a real journey involved. The answer appears around the necks and shoulders of those who live in that world in which patterns, colors, fabrics—and the marketplace in which to acquire them—is a part of one’s daily existence. And just as much, on display next to them, is the food purchased not on a weekly basis (or online!), but on a daily basis, the daily basis of color and pattern that one sees in baskets of apples, squash, fruits, vegetables and all manner of things that have come from the earth. This is the thread that ties us to our origins.

Markets have their function in societies as a place to collectively provide for the basic needs that humans have. These basic needs have not changed, but for many of us, the method of their distribution has. We, who live in another world, of plastics in silvers and grays and blacks, on the other side of the planet, have a different life, one that takes us away from the intimacies of a fabric dealer in a marketplace. Gilbert brings us back there, but also to an entirely new place; not literally to one of the marketplaces I’m referring to, but to an imaginary locale, undeniably reminiscent of this part of human history. This is the place that Gilbert wants to explore, the point of divergence between these two worlds, the point at which encountering and maintaining the vital origins of human needs comes into question. It’s not that Gilbert goes around the outside of the inevitable cultural references and in through back door. No, it’s a question of the purely visual. Gilbert uses his eyes to guide the modern technology of digital reproduction, while at the same time assuring us that this technology is not subverting the essential human needs, and the basic joys of decorative pleasures encountered in the course of satisfying those needs.

“Youth Day-Krakow” Printed on Aluminum 72 x 10 inches each, four panels

Is there some other analysis that I should apply to what he shows us? Is there something wrong with experimenting like this and sharing the results? Is there some approval or disapproval of visual experimentation, some need for direct social context or commentary instead? No, there is not. This is a modern malaise, I think. Let life be what it is. I could go deeper in this regard but I’ve speculated enough. Gilbert himself will only smile slightly and return to discussions of pixelation, saturation, printing. I feel he chooses to stay upon this known territory of discourse in order to let us make our own analysis, as I have. I don’t feel that he is a scientist given to speculation or allusion. I don’t feel that he was comfortable making or replying to speculative cultural references. But they are there in what he shows us. At the core of this exploration, Gilbert is concerned with the connections, decisions and chance results which scientists are forced to confront during the course of their research, which then in turn, the viewer of his artwork makes about his art. At the core of his explorations is the fundamental question, “Is artistic creativity different than scientific creativity?” It’s the process he confronts, more than the conclusions. He is more than willing to let the visual event stand for itself. Gilbert simply uses his talent and tendency for methodical research and directs it toward his individual artistic exploration. Methodical, yes, and we are the better for it, since he is a methodical tour guide. This is the work of a sophisticated brain with an openness to the playful nature that all humans, even in the most basic circumstances, can aspire to. But he’s gotten there through his own individual processes. He takes us to places unexpected, vital and enigmatic; places perhaps even more vital and compelling than the marketplaces themselves, because Gilbert has made his own journey and arrived at locations unexpected, surprising and fulfilling. Gilbert releases us upon these foreign shores, and we are free to explore them as we see fit.

Let me conclude my metaphor and sum up: In the course of this artistic journey, as captain of his ship of exploration, we are the passengers and observers that Gilbert takes along with him. He will lead us to these new places, and we accompany him willingly. We are passengers on this journey, but if he chooses not to overtly reveal the precise thesis which he is pursuing in his journey, (his artistic endpoint, if there ever is such a thing), we are confident that he will share his progress and conclusions with us. It is an act of generosity, because he wants each of us to come to our own conclusions.

There is another possibility, however, that he explores just for the sheer joy of exploration. Not as the driven scientist, but rather as the open-minded emissary of one world to another. It is the simple pleasure of taking the next step that keeps Gilbert moving forward. As he traverses the multiple pathways which each series of images presents to him, he welcomes us as his passengers, viewers and compatriots. Fellow explorers we become, as well as fellow ambassadors from one world to another. And if he takes us to distant locations where sounds, flavors, colors and patterns are different and perhaps more compelling than those we see in our accustomed environment, we are the better for it. For when we enter this metaphorical marketplace and see these colors and patterns all around us, it becomes an experience that we could not have had without the guidance of Wally Gilbert, our captain and chief explorer. I, for one, feel that it’s a vital journey well worth taking, and I look forward to the next one. No passport necessary, just get on board.