Metamorphosis”—“…a transformation, … change in form from one stage to the next in the life of an organism…” definitions for this word from Webster’s that Basha Maryanska and Kathryn Hart aptly chose for the title of their recent dual exhibit at the Howland Cultural Center in Beacon, NY.

Here, both Maryanska and Hart demonstrate their formidable talents in forty-seven works, using their own reactions to repeated personal catastrophes, vanquishing anguished memories through pieces of drama and depth, providing a transforming emotional experience for anyone lucky enough to have had the opportunity to view them.

Close personal friends and creative soul mates, they did not join forces here cynically, but resolved to turn their pain into triumphs of creativity. Hart accomplishes this in her mixed media sculptures, while Maryanska uses her emotions as catalysts for the exuberant colors flowing from “head to heart to arm” in her paintings, turning a harsh life history into poems to a higher power, the artist acting as an amanuensis to the divine soul.

Maryanska’s triptych, “Memories—It Happened, We Remember, If Walls Could Speak,” a dark acrylic documenting the suffering of the Polish people throughout modern history was the first painting on the gallery wall. The artist, from an old historic family, lost everything from the brutalities of World War II and the succeeding years of Communist rule and this piece is her testimony to what happened.

The painting, an anguished telling of this history, has a bleak white feather superimposed on the canvas surface as a symbol of a quill pen, chillingly documenting the brutality. It coolly floats over an angry red gestural brushstroke that seemingly forces its way into a somber field of decimated building shells. These three panels, Maryanska’s reporting of atrocities from a psychological distance, is a piece, the artist said, that she brought with her wherever she exhibited, as her way of never forgetting what was endured in her country, the work forcing visceral responses in viewers.

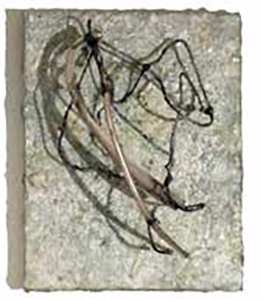

Kathryn Hart, “Cellular No 2”

Sculptor Kathryn Hart was originally a watercolorist and transferred her ability to layer on washes to her sculpting technique where she repeatedly builds up strata of materials so that the pieces’ surfaces become blistered, wrinkled, and torn, what the sculptor likens to the visible exteriors of “human beings living life.” Growing up as the daughter of a surgeon, she is well acquainted with medical life-saving acts that she transferred to her sculptures after watching her father work, interpreting his skills in her own pieces. Arduously building her sculptures by hand, constructing and pulling the elements apart repeatedly, her past immersion in the seriousness of medicine throughout her life and her own experience as a survivor of grave illness, gave her up-close observations of life and death, her sculpture providing her a continuous vehicle to work out her feelings about personal misfortune.

Here, Hart combines disparate found materials as she does in almost all her sculptures, physically deforming them into jarring new entities. Her mixed media assemblage, “Coda,” took six months to complete as the sculptor saw it as a resolution over a period of time of her serious personal circumstances, with a newly found positive feeling arising upon completion.

In “Coda,” Hart rests a solid steel beam on a built up rectangular base dividing it into two equal parts, a strong foundation and connector of all opposing energies swirling throughout the piece, while a jumble of barbed wires is suspended over it. When light shines on the wires, curvilinear shadows form on the walls at the sculpture’s back, dynamically moving the viewer’s eye in myriad directions. Wisely anchoring this motion with the solid metal base under the tangled mass, tiny glass bottles are also attached throughout the suspension, causing light refractions when rays hit, evoking a mesmerizing luminosity. She chose the title, “Coda” as a way of saying the long time of emotional darkness was now supplanted by an emerging optimism, tacked on like a musical afterthought, as a counterweight to the sculptor’s past struggles helping her to rise from tragic ashes, and so, continue living.

Both painter and sculptor in their need to rise over personal pain, saw this opportunity to exhibit as a statement that life is worth living and the changes a person has to experience throughout are the necessities for survival. In contrast to the somberness of her triptych, Maryanska, in her mixed media collage,“The World Apart,” joyously exalts her life, expressing great good fortune at her ability to live in both city and country while Hart joins the celebration in her “Cellular Series” –new assemblages named for the smallest organic entity that in spite of experiencing huge obstacles, miraculously grows into fully realized perfection.

In “The World Apart,” Maryanska combines her impressions of urban New York City and the bucolic Hudson Valley where she maintains residences, integrating the robust energies of skyscrapers soaring to heaven on a vertical axis, with two lushly painted ultramarine horizontal fields at the canvas’ top and bottom, shimmering representations of a sapphire river and an intense azure sky at opposite ends, framing the piece.

She balances vertical collaged thrusts with perpendicular paint strokes, the juxtaposition giving the entire piece stability. Supporting this sense of equilibrium, the artist adds black and white jagged pieces of painted canvas, intimations of tall, silhouetted sailboats, bobbing over flowing waters while subtly affixing a blue- green orb near the buildings’ apexes, the only rounded object in the piece.

Basha Maryanska, “The World Apart”

Perhaps this is the painter’s way of representing both earth and sun, connecting the organic qualities of the river and sky as if to say a man-made city can only exist if it respects its primordial, natural foundations. Maryanska told me she has to have both city and country in her life to maintain psychic balance. Through the act of creating this piece, the artist is able to join both.

Sculptor Hart pushes the viewer’s visual boundaries in a new group of 12 mixed media pieces entitled “Cellular Series,” incorporating wire, bone, marble dust and resin in all. The works are built-up, chalk white squares of dense paint layers that the sculptor, almost through an alchemical process, textures and deformes, using heat, chemicals and pressure, to create new entities. In front of the geometrics, she dangles wires and tubes, chaotically jumbled, but at the same time, maintaining a delicacy in their suspension, seeming to float the totally entangled metal threads as one object in the surrounding air. As in “Coda,” when light shines on the piece, the spaghetti-like tangles create bold shadows contrasting with the grounds of equilateral shapes, making visual lines resembling abstract gesture drawings, changing the images according to the light’s direction. The resulting shadows, sometimes agitated, at other times serene, are the sculptor’s impressions of the microcosmic level of the universe, cells, teeming with all type of organic life but always miraculously organizing themselves into cohesive forms. Metaphorically, this series is one of evolution personally symbolic to the sculptor of the triumph of hope, an impetus for survival, no matter the extent of the situation’s gravity.

The incorporation of the use of white plays an important part for me in both Maryanska’s “Memories” and all of Hart’s sculptures in that I can concur with the artists, through their choice of this ghostly color, that the possibility of death is always present throughout life and we must combat it’s finality by fully living.

Although Basha Maryanska and Kathryn Hart work in different mediums, they reveal powerful, shared threads, weaving works of deep emotion, bearing witness to their own profound life experiences, the results a working through painful memories as artistic statements of victory. Their needs to create impelled them to realize works as anchors for lives battered by the roiling seas of their pasts. This exhibit was their magnificent opportunity to tell us about what they have suffered and most importantly surmounted.

“Metamorphosis” recently seen at The Howland Cultural Center, Beacon, N. Y.