One of the most common mistakes made by contemporary artists enamored of Buddhist meditation is attempting to imitate the brush and ink techniques of the literati artist-poets of ancient China and Japan. Perhaps the most obvious examples in the West, although he never acknowledged their influence upon him, was Franz Kline, whose large black and white oils on canvas are often compared to those Asian masters for their apparent spontaneity. Over the years since his death it has become known, however, that Kline carefully sketched his calligraphic forms in brush and ink on the pages of a phone book, before blowing them up and tracing them in oils with a broad house painter’s brush and the help of an opaque projector.

The immortal Basho would have laughed his head off at the lengths to which this 20th century American abstract expressionist went to create the illusion of a gestural spontaneity which, in Zen ink painting, is a product of spirit rather than technique.

The 21st century Japanese painter Takashi Kasai, on the other hand, does not attempt to create illusions of effortless grace and enlightenment. Rather, he expends considerable effort, in the meticulously painted large-scale acrylic compositions on linen that make up his “Eternal Meditation”

series, to evoke the stillness, volumetric solidity, stoic expressions, and gleaming bronze or matte sandstone surfaces of the figures in Buddhist temple statuary. Thus, through his own painstaking work process, Kasai projects the rigorous effort (as opposed to the “instant karma” or easy Nirvana

imagined by spiritual faddists, especially in the West)–– that meditation actually demands of the true devotee. If only one could look beyond the serene features of the meditating statue, with its heavy-lidded eyes and cupidic little hint of a smile, the artist appears to be telling us, one might see an entire world of turbulent inner struggle.

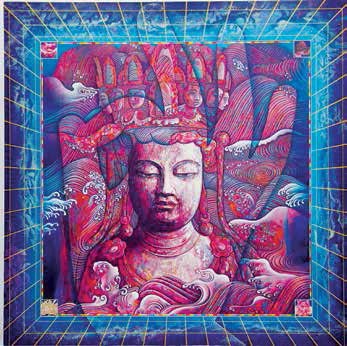

From the Eternal Meditation Series

In one intricate composition in a perfectly square format, the bust of the Buddha is enclosed within a painted frame decorated with a precise linear grid that enhances both the sculptural and metaphysical

qualities of the image within, by creating the optical effect that the squares are alternately advancing and receding on the picture plane. On the Buddha’s head sits a tall crown of almost papal elaborateness adorned with several semitransparent faces, perhaps representing his several previous

incarnations. All around the figure, sinuous waves, delineated in the actively decorative manner of Hokusai, enter the picture space, reaching almost threatening-looking tentacles toward the Enlightened One –– as if to “blow his cool,” so to speak. Rendered at large contemporary scale in oil on canvas in

the manner of Buddhist temple paintings in colors on silk, rather than in the swift, spare, monochromatic style of literati ink painting, this picture enshrines the meditating statue as a mythic Superhero of contemplative inaction.

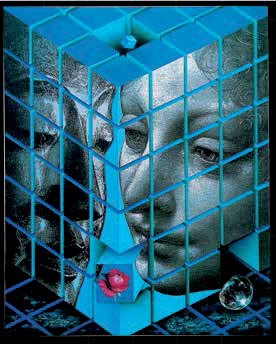

From the Eternal Meditation Series

Another picture in the series depicts two incongruously matched faces within a blue gridded cube resembling one of M.C. Escher’s spatially ambiguous optical conundrums: that of a male Buddhist

temple sculpture and that of a gold-ringleted Western beauty, resembling one of Botticelli’s classical goddesses. Since one square at the bottom of the grid is missing, the opening’s inner depth–– out of which a crystalline oval appears to have rolled like a mystical egg from a geometric womb –– suggests that the grid is composed of stacked cubes. Yet a slight perceptual shift on the part of the viewer

repositions the grid so that its overall effect is of a cage, in which the two faces are locked

in stifling but seductive proximity. Indeed, the dewy red rose, set against the brilliant blue exterior of the cage at the point in the composition where the lips of the two figures almost meet, can only be seen as symbolic of worldly desire. And while, unlike the avatars of most more formal belief systems,

the Buddha did not impose moral restrictions on sexual expression, he did recommend celibacy as one

possible path to worldly renunciation and purity of mind.

Yet another large canvas in the series appears to depict the attainment of that serene spiritual state

at which one apparently endeavors to arrive through meditation undisrupted by external reality. The large reposeful face of a Buddhist statue with lowered eyes, seen in three-quarter profile, dominates the canvas. Although it is obviously composed of solid matter, it is semitransparent with silvery, gently swirling circles visible within and around it, suggesting the qualities of “Eternal Meditation” as they are expressed in the lyrics of that poetic Michel Legrand song: “Like a circle in a spiral

/ like a wheel within a wheel / never ending never beginning/ on an ever spinning reel / as the images unwind / in the windmills of your mind…” That Takashi Kasai has given solid painterly substance to subtle and complex aspects of such an ethereal and elusive subject makes this, his first solo exhibition in New York, a most auspicious debut.